There is already a wide choice of new and established wild flower identification books on the market, and so it takes something pretty special to stand out, and that is exactly what this latest addition to the WILDGuides series achieves. British & Irish Wild Flowers and Plants: A Pocket Guide is a gamechanger. Unlike some of its competitors, the focus of this new field guide is clearly on what a beginner botanist needs to know to identify wild plants for the first time, rather than assuming any prior knowledge.

The challenge in producing a pocket guide is deciding what to leave out. The authors of this 320-page volume have sensibly narrowed the species covered to those which can be considered widespread. Some plants which are very likely to be found in uncommon habitats, such as saltmarshes, are also included, as well as common ferns, conifers and grasses and their allies, which is unusual but extremely valuable in a book of this size. And it is the first compact field guide I have come across which includes winter twigs. An infectious enthusiasm for plants is evident in the introductory pages and there are just enough definitions and guidance, with additional botanical information, to provide the tools and context needed for identification.

View this book on the NHBS website

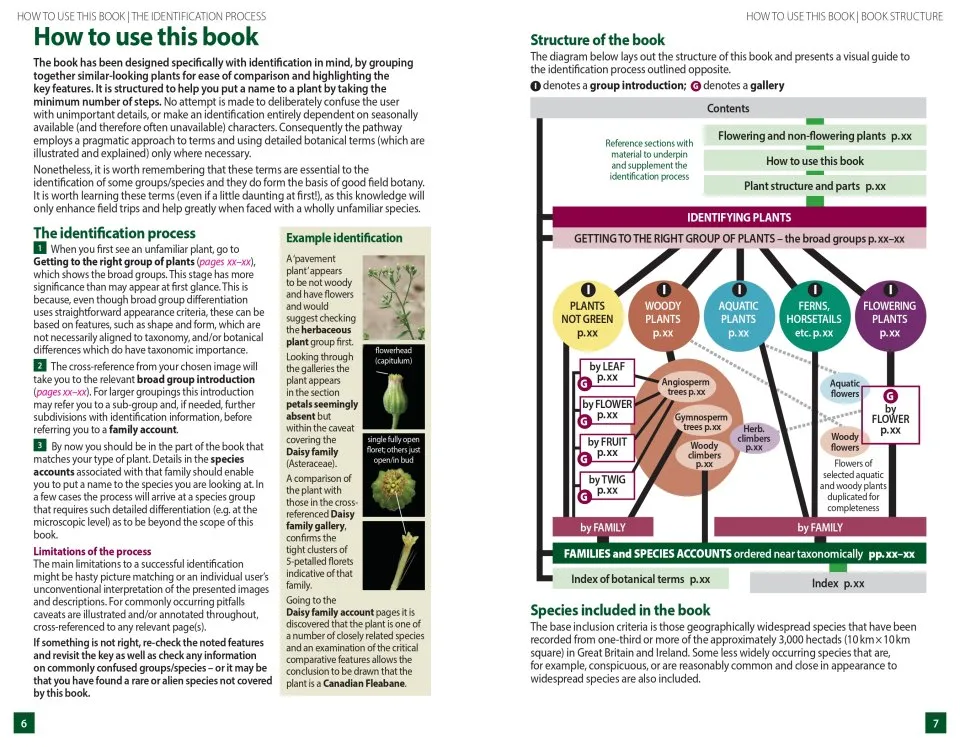

One of the most dispiriting and unsatisfactory experiences for a new botanist is the need to ‘page flick’ through a whole field guide to try and match the flower they have found to an illustration. Here, a clear and pragmatic process is set out to help someone new to wild flowers narrow down their find to a group of plants, so that they can quickly zero in on the likely set of species descriptions. Identification keys for plant families have always been notoriously difficult for beginners to navigate, so this is a real achievement.

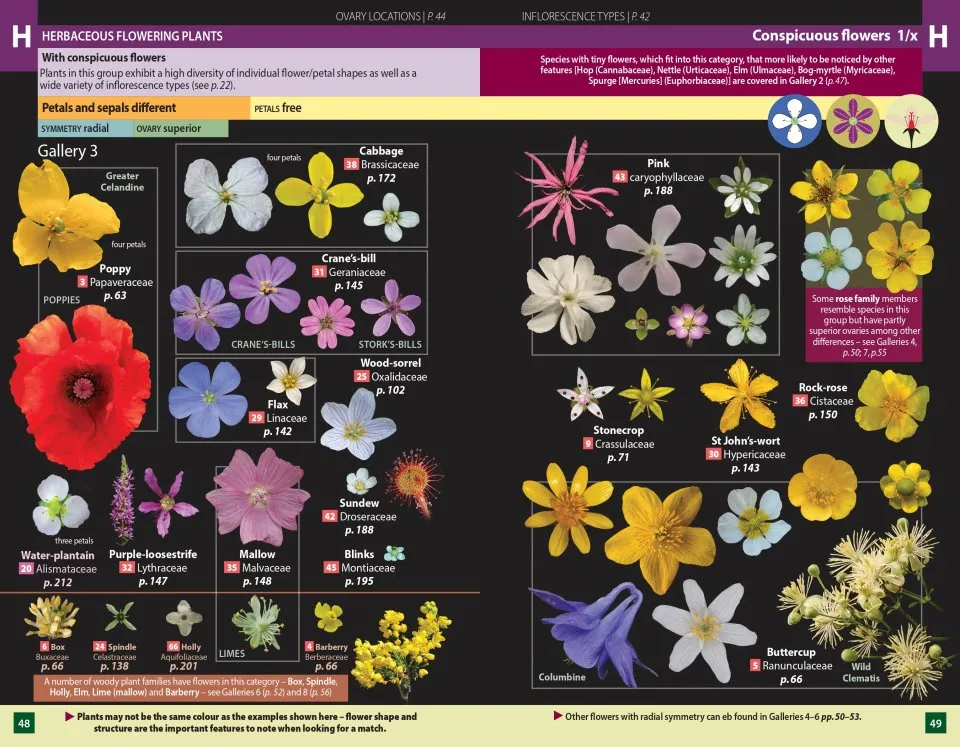

The suggested first step of the process is to consider whether the plant lacks chlorophyll, or is aquatic, woody, or has inconspicuous flowers. For plants with conspicuous flowers where none of those earlier categories apply, then the next step is to check the flower’s appearance and three aspects of its structure against a series of photo ‘galleries’. The gallery photographs are annotated with page numbers for the group, and a handy chart is given on page 66, to get to a best-match. Advice is given on what to do if the process does not take the user to credible identification, with commonly occurring pitfalls highlighted.

Throughout the book, the botanical information, galleries and species accounts are illustrated with high quality annotated photographs. Species descriptions include close-ups of the key characteristics and distribution maps from the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland’s Plant Atlas 2020. Given what this field guide has achieved, it seems somewhat churlish to note that, as an incredible amount of information has been packed into a small volume, the page layout can appear a little cluttered in places. Thankfully, thoughtful design means that this is unlikely to get in the way of understanding, and I am guessing that a reader will quickly become familiar with how the information is set out.

I am often asked to recommend a field guide for the introductory identification courses I teach, and this will be top of my list going forward. And while its value for beginners to wild flower identification is clear, it could also help intermediate field botanists plug gaps in their knowledge, help them separate out some of the trickier or newer widespread species, and provide ideas for how best they can themselves share their knowledge with beginners.