Ted Green came to a standstill under the canopy of the old oak. He caressed the rippled bark with a weather-worn hand.’ The opening sentences of Isabella Tree’s Wilding are most readers’ introduction to the author of Treetime. Ted’s interest was not in wilding, but in the sorry state of Knepp’s ancient oaks, which he diagnosed as due to ‘ploughing… and everything that comes with it’. His visit proved to be an epiphany for Isabella Tree and Charlie Burrell, for the Knepp we know today is primarily a result of their decision then and there to protect its oaks. Ted calls Knepp a giant fallow project to allow the soils to recover from their decades-long bath in agricultural toxins, but of course it has led to so much more.

Ted recalls his feral childhood, living on the edge of Windsor Great Park and teaching himself natural history ‘bottom-up’ by exploring the local woodlands, meadows, hedges and parks. As a plant-pathology technician at Imperial College’s Field Station at Silwood Park he learned more formally about fungi, which grew in profusion on the ancient trees he knew so well (32 years ago he wrote about this ‘forgotten army’ of woodland fungi for British Wildlife). Nowadays, mycorrhizal fungi are the stars of popular books, but many of the questions Ted was asking back then about the relationship of fungi and trees remain active topics of investigation.

Ted’s middle name must be ‘iconoclast’, because he constantly challenges received wisdom, those ‘unsubstantiated, unquestioned, sweeping statements and myths’ we all carry with us. He is a self-confessed troublemaker for bad practices in conservation, but he is also a creative thinker about solutions and the future. Thus, posing the deceptively simple question, ‘what is a tree?’, gives him an opportunity to rail against ‘plantation-planting paranoia’, to plead for more ‘treecologists’, and to promote the multiple benefits of open-grown trees. Treetime’s many photographs of open-grown trees tell their own story; these are individuals of wonder and beauty, to be cherished and protected. Unsurprisingly, Ted was one of the founders of the Ancient Tree Forum, whose mission statement was ‘no further loss of our ancient trees’. Documentation, he reminds us, remains patchy, so he urges all of us to get out and map the veteran and ancient trees in our own districts.

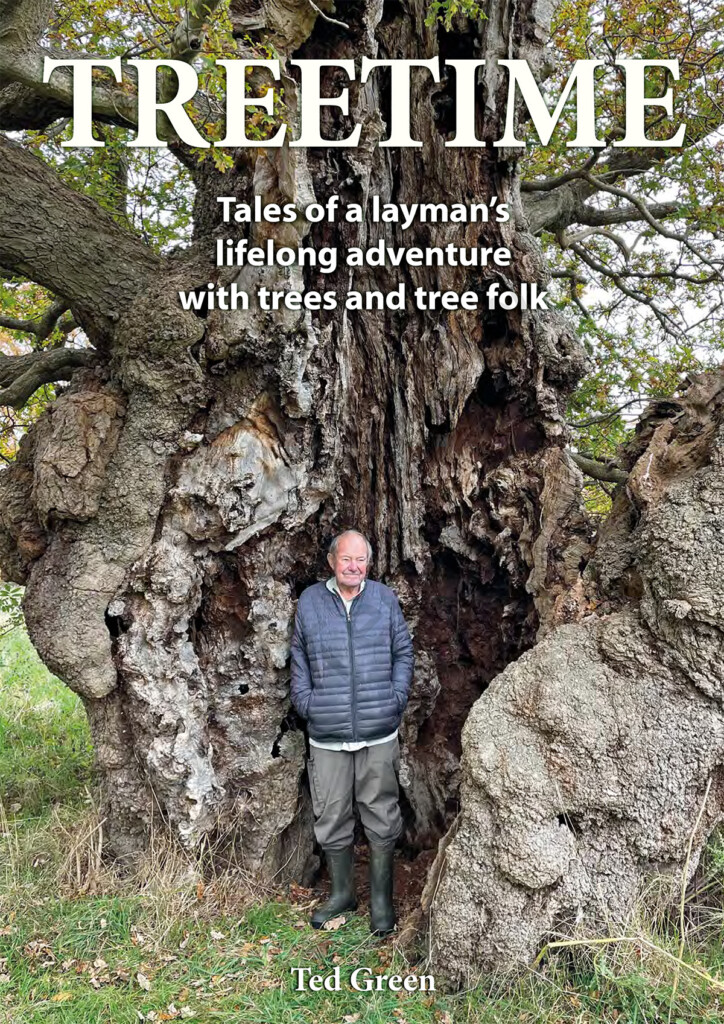

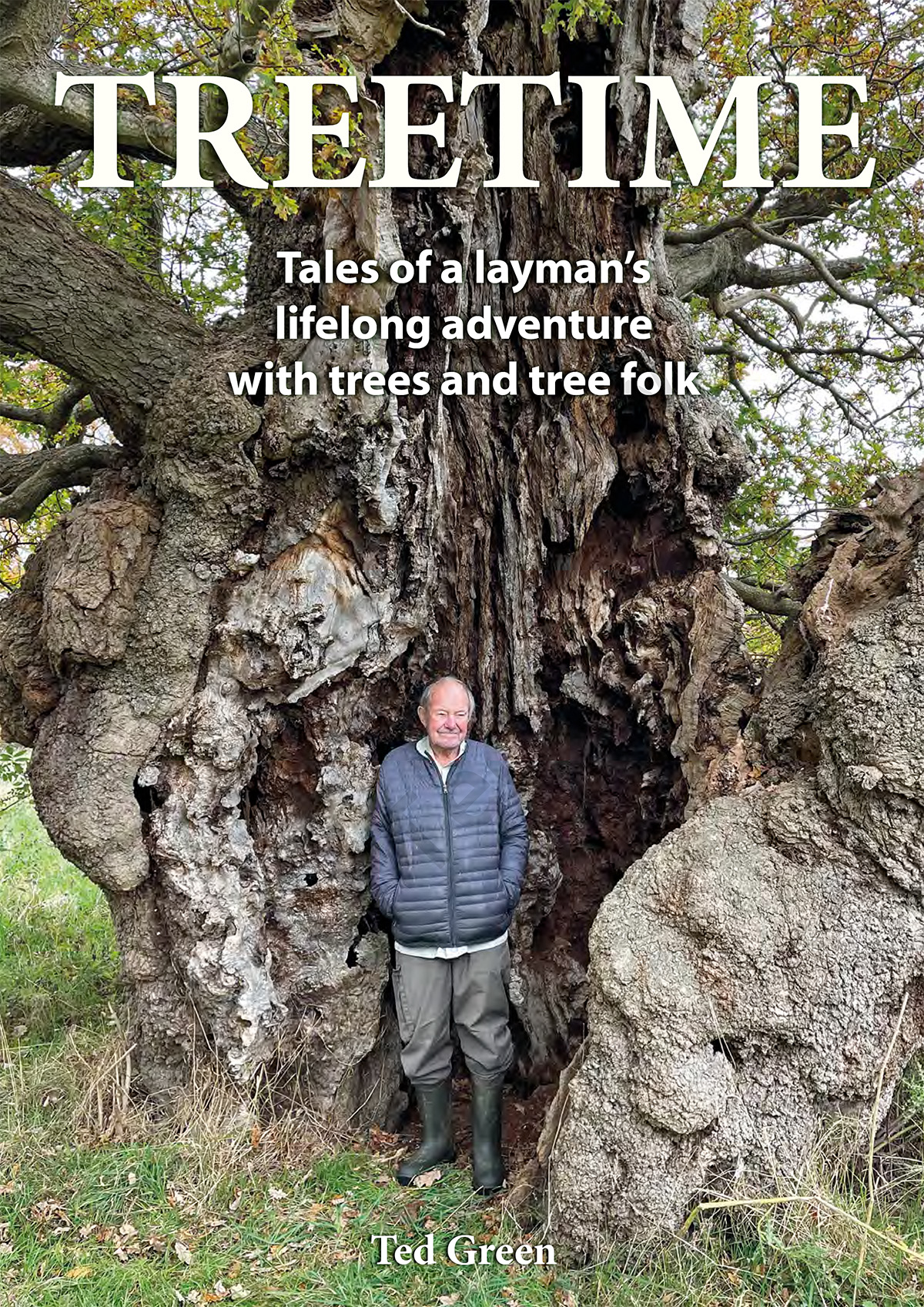

Ted has ranged through the world’s woodlands and tree conferences, as at ease with kings as with commoners, uninhibitedly offering his opinions, debating, discussing, delighting in being a gadfly, often expressing frustration at the pace of change, but throughout he is a passionate, articulate and amusing advocate for trees. With an entertaining personal story on nearly every page, Treetime can be read effortlessly in a single sitting, or, as a bedside companion, it can be dipped in and out of without worrying whether it is a page you have already read, for Ted makes you feel as if you are having a one-on-one conversation with him. He credits Sarah Bryce for giving his text its intimate, durchkomponiert quality and Jill Butler for giving him space and time to think, but in Treetime all of us can share Isabella Tree’s experience of ‘meeting a remarkable man under a remarkable tree’.