Robert Wolton is one of those rare people who combines a scientific understanding of ecology with highly pertinent practical experience plus an ability to communicate in an engaging way. This book reflects the man and his personal experience as a farmer and expert who has led government delivery of farm-advice programmes across England and has been a leading light in the organisation Hedgelink. It is extremely well written, with 16 logically sequenced chapters full of referenced research, practical examples – often with personal anecdotes – and many photographs and diagrams that beautifully illustrate the narrative.

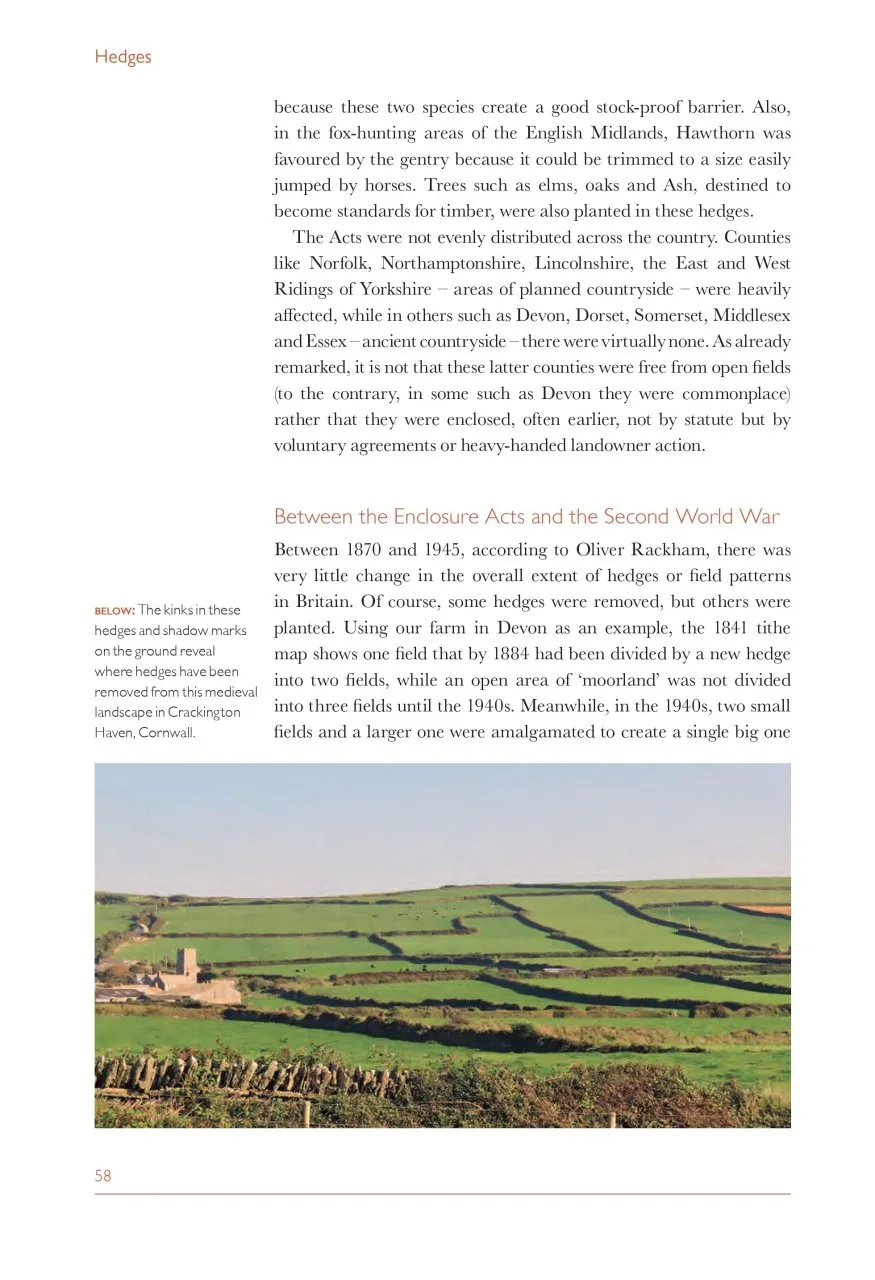

The first few chapters give a grounding in what constitutes a hedge, together with cultural origins and history and finally how hedges have fared since the Second World War, when national agricultural self-sufficiency and increasing intensification have left a legacy of fewer hedges, many of which are in poor condition. Nevertheless, we still have enough hedges to stretch to two return trips to the moon! As with reading the great Oliver Rackham’s book, The History of the Countryside, there are a number of revealing Eureka moments. For example, who knew that field shapes in less disrupted (‘ancient’) countryside still reflect the reverse ‘S’ and ‘J’ shapes created by medieval ploughing by oxen?

View this book on the NHBS website

We then move on to the various elements of hedge architecture, biology and ecology and how hugely important hedges are to wider species conservation. Each of these chapters has titles that let the reader know which structural and functional aspect is being discussed (‘The Shrub Layer’ etc), and go on to present plant, fungus and animal groups that can thrive in these habitats. Wolton gives fascinating accounts of why certain well-known species – Hazel Dormouse, Greater Horseshoe Bat and Devon Whitebeam, etc. – are now highly dependent on hedges, particularly in the intensively managed lowland landscapes. For example, Greater Horseshoe Bats use hedge lines as linear highways and have developed elephant-like mental maps of these that are passed down through generations. There are, however, a large number of less well-known plant, fungus and animal species that are seemingly hedge-dependent, and Wolton highlights some of these in text boxes with photographs. For every species highlighted or just mentioned in the text, Wolton includes at least a brief account of how biology and ecology link with that of the hedge, and I found these accounts continually fascinating and never repetitive.

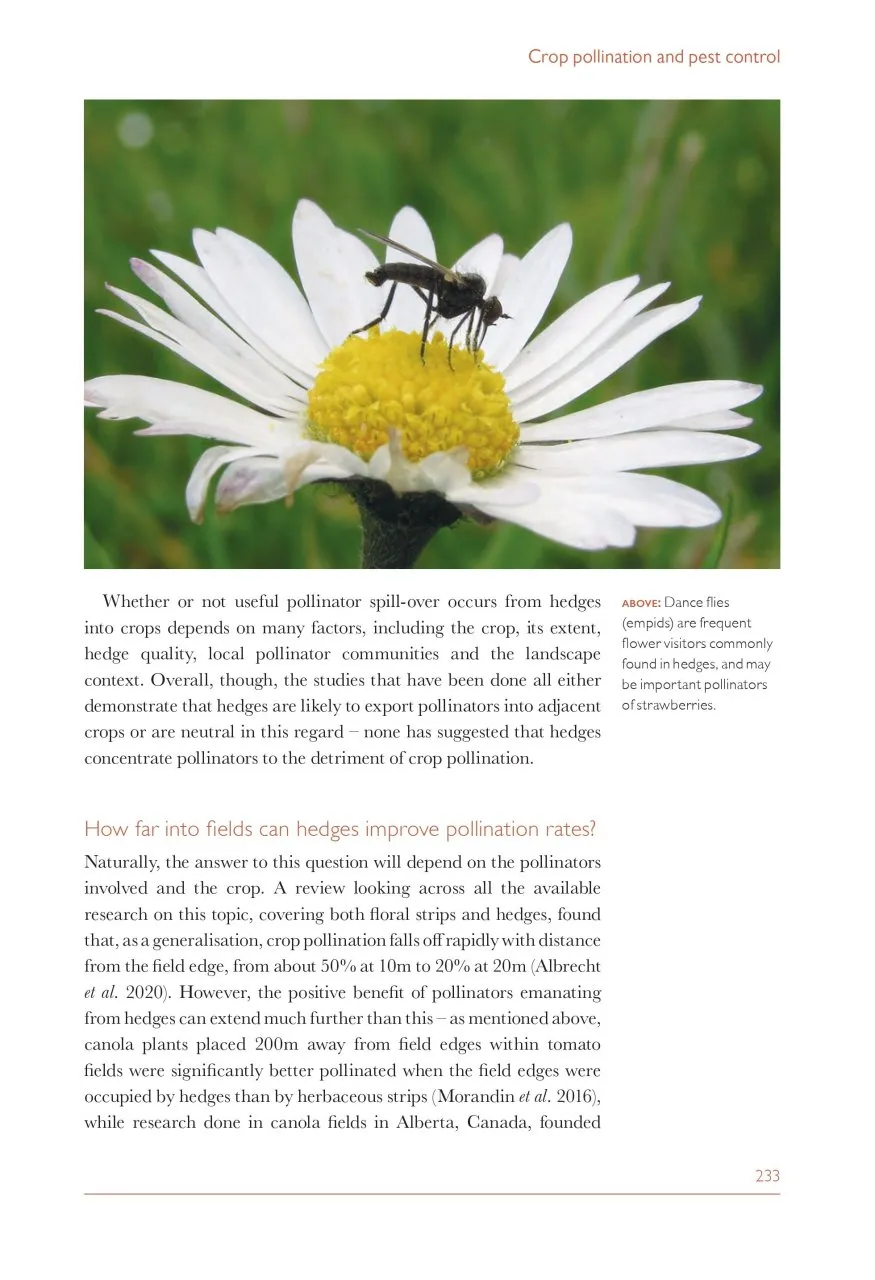

The next section looks at the uses of and ecosystem services provided by hedges. Wolton rather cleverly brings the reader in a cycle to show how historical uses of hedges that have largely become obsolete, such as for wood fuel, could quite easily give hedges increased cultural and financial value in the modern world. He is always able to back up his arguments with actual examples from his farm or from other projects and research, offering, for example, summary figures regarding monetary value or carbon capture. Topics such as soil conservation, flooding, crop pollination and pest control are also discussed in some depth here and drive home how the dependency on modern ‘fixes’, such as increased pesticide use, need not be continued at current levels if hedges were incorporated in integrated pest control, crop pollination and flood amelioration measures and managed accordingly.

In the penultimate chapter, Wolton tackles the contentious topic of hedge management. In previous chapters, I raised my eyebrow at his positive take on hedge-trimming. I know this is a matter that creates great anger across the British countryside, where hedges are annually ‘smashed’ with tractor-mounted flails, resulting in skeletal wooden fences that provide neither shelter nor food for wildlife. Wolton gives a good account, however, of how relatively heavy-handed management can improve hedge habitats if done with just a few tweaks. For example, incremental cutting or introducing rotational cutting on a three-, seven- or even 15-year cycle would massively improve the habitat and particularly the availability of flowers and subsequent fruit crops. I like the fact that he mentions Ecological Tidiness Disorder (ETD) as a peculiarly British ‘disease’ and the bane of wildlife enthusiasts.

It would have been good to see discussion of ways to restore and increase hedge-bank floral diversity by, for example, haying or the use of suction flails. Such methods remove the cut biomass which otherwise builds up fertility and litter, both of which are the enemies of floral diversity. I understand that this is not possible as a widespread management regime, but, given the poor floral diversity of most hedge banks, it is surely worth promoting. I have seen hay-making on road verges next to hedges widely used in France and Belgium.

Nevertheless, such a thoroughly well-written, illustrated and researched book is a joy to read and should be mandatory reading for every countryside worker and land manager.