Time was when birders looking for entomological diversion during the quiet summer months followed a well-trodden route, from butterflies and moths to dragonflies and damselflies. For all their attractions, shieldbugs remained a minority interest, probably because until recently there were few accessible field guides to them.

Nowadays, shieldbugs and their connoisseurs are better served. They have new and enthusiastic champions, among them Richard Jones who has given us a highly readable addition to the Collins New Naturalist series. With around 80 species in the UK, shieldbugs have a lot to offer: they are a manageable group, including a seductive mix of the common, the rare and the elusive. Many are relatively easy to identify and tend to stick around long enough to let you do just that. According to Jones, they ‘walk with a friendly clockwork waddle’. They are pleasingly shaped, attractively marked and can be good barometers of climate change. As Jones asks, ‘What’s not to like?’

View this book on the NHBS website

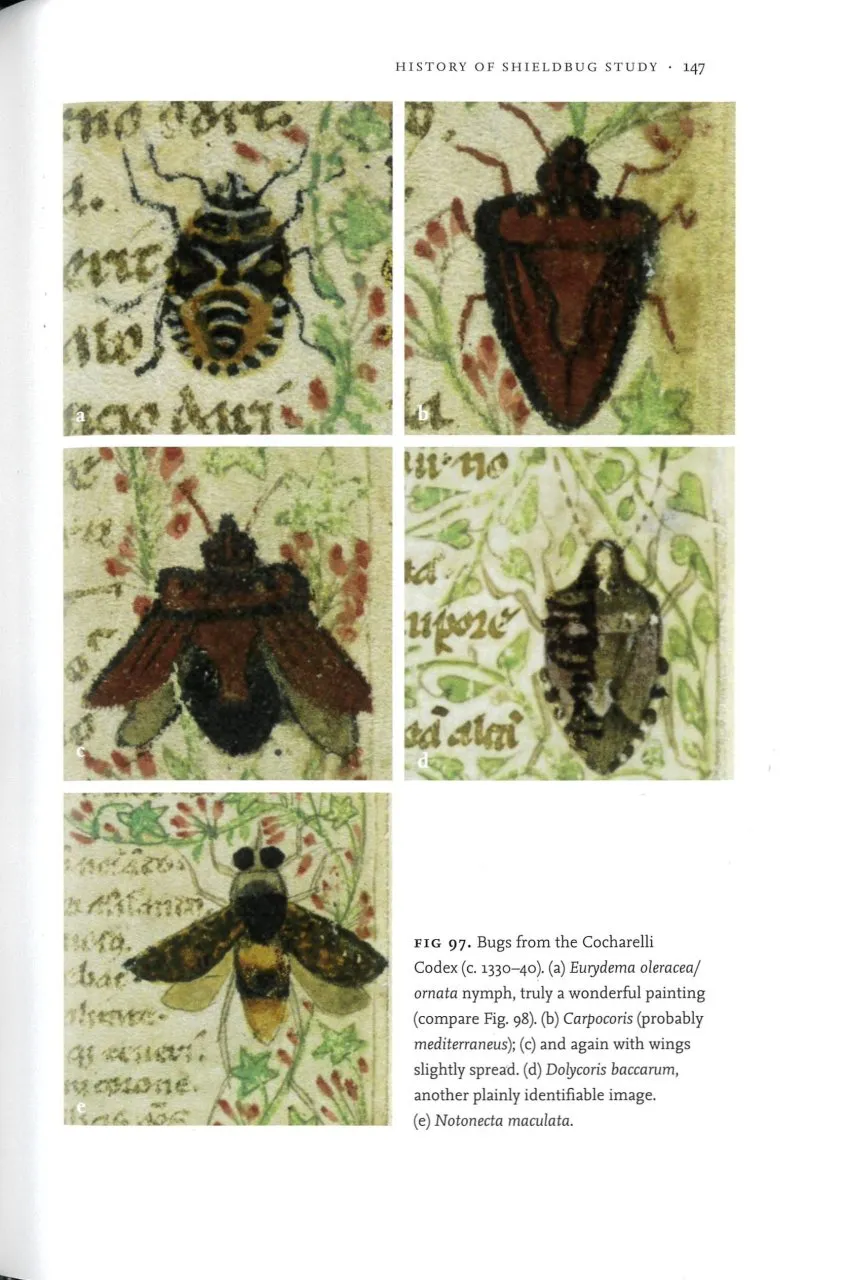

He begins by defining shieldbugs and locating them in the huge order Hemiptera, which includes water boatmen, leafhoppers and cicadas. Shieldbugs are not all shield-shaped and Jones opts for a wide definition, including such species as Western Conifer Bug (an introduced squash bug), the firebugs, and the solitary wasp mimic Alydus calcaratus. Chapter two covers shieldbug structure, even managing to squeeze in a topical reference to Barbie dolls, followed in chapter three by accounts of how the insects live, from mating, egg-laying (Green Shieldbugs have ‘emoji-faced’ eggs), and in some cases the rigours of parenthood. Anyone who has disturbed shieldbugs in the garden will be aware of the pungent odour that many emit when threatened, and I was especially interested in ‘shieldbug alchemy’, an absorbing summary of the chemicals that they use to deter predators. This defence does not always work, as demonstrated by the recent spread of some parasitoid tachinid flies in the UK. Further chapters examine shieldbug evolution and the surprising number of people who have studied them, from Aristotle and Pliny the Elder up to the present day.

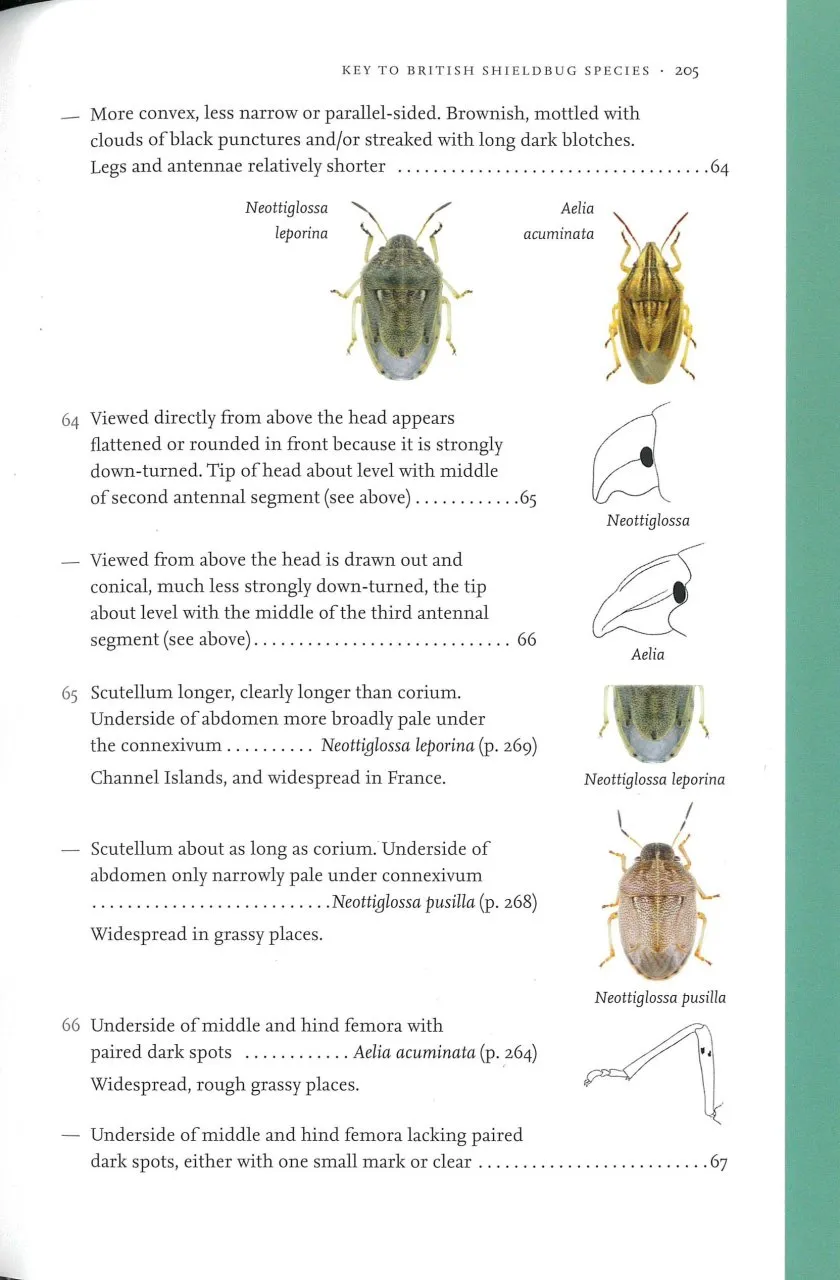

At the heart of the book is a dichotomous key to over a hundred species of adult British shieldbugs, illustrated with photographs, drawings and diagrams. Although I have not had a chance to use it in detail, it seems robust and well designed, with the proviso that it does not illustrate nymphs. These can be confusingly different from adults in many species, and the nymphs of some, for example the small black Legnotus bugs, can be confusing even to seasoned hemipterists. A number of nymphs are, however, illustrated elsewhere in the book.

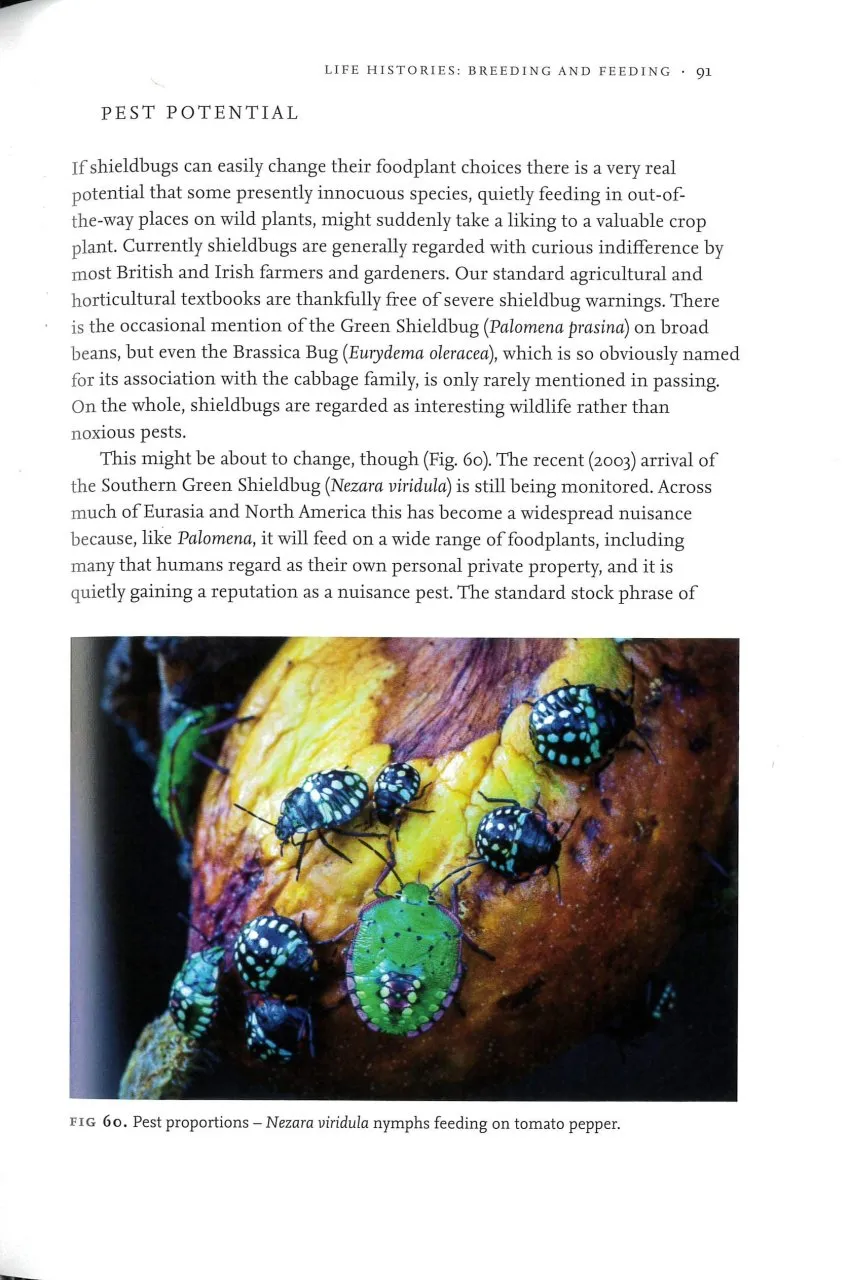

For me, relatively new to the group, the real revelation is the chapter devoted to species accounts. In nearly 150 pages we meet the 79 shieldbugs, squashbugs and close relatives which currently occur in Britain, plus another 11 known from the Channel Islands and 16 aspirational species which may or may not make it here from mainland Europe. There is a handful of others, too, including the Western Conifer Bug, a North American native which has colonised Britain (including my local cemetery), and the Brown Marmorated Shieldbug, from east Asia, whose imminent colonisation has been trumpeted by the media. Most species are clearly illustrated with photographs and described with brief notes on behaviour and distribution. There are no maps, partly, I suspect, in order to save space, but also because, for many species, these would soon become out of date. Juniper Shieldbug, Box Bug and the red-and black Corizus hyoscyami, to name but three, have undergone dramatic increases over the last decade or so and, as Jones demonstrates, there is potential for several more shieldbugs to colonise or spread within Britain and Ireland, given the influence of climate change and movement of horticultural goods. This is probably the first time all these species have been described and illustrated so accessibly in one volume, and for this reason alone the book is worth owning, as a spur to recording shieldbugs – there is advice on how best to do that, too.

I have very few quibbles and have relied on a hemipteran-expert friend for advice on photo captions. For example, figure 24 on p. 30 seems to show a Green rather than Southern Green Shieldbug, and figure 28 on p. 35 looks like a Birch Shieldbug rather than a Hawthorn Shieldbug.

But these are minor matters in a lucid and entertaining book, which should be on the shelves of every naturalist. It might not knock the moths and dragonflies off their perches, but it will give shieldbugs their well-deserved place in the sun and inspire beginners and experienced entomologists alike to study and appreciate them.