I am a great believer that, if asked to review a book, one must read it from cover to cover. Guided by that rule, I found Trees to be a real challenge; it is so full of pertinent and useful information that it has taken days to get through its comprehensive, well-written and informative text. With so much emphasis now given to woods, forests and forestry, it is astonishing how little most ecologists and foresters actually know about trees as individuals – we are nearly all, I suspect, cheerfully ignorant of the biology of trees! With the publication of Peter Thomas’s excellent New Naturalist edition, however, there is no longer any excuse to remain unaware of these organisms and their complex life histories.

Trees are an extremely variable bunch; cherry trees are as different from pine trees as fish are from mammals. They arise from a very wide array of plant taxa and, as such, are not a natural grouping of organisms. They can be found as prostrate woody shrubs, magnificent tall redwoods, short-lived birches, or long-lived Kauris. One tree, the Western Australian Christmas Tree Nuytsia floribunda, is even parasitic, having evolved underground secateurs that cut through the roots of other plants to plumb into their vascular systems, and has been recorded as even cutting underground wires in order to try to attach itself to them! Thomas puts his wealth of knowledge and understanding to good effect in addressing this variation, and the challenges faced by plants that have ‘chosen’ to be trees. The message is that trees approach the problems of water distribution, water stress, nutrient acquisition, growth, seed dispersal and pollination in a range of different ways, and that they are far more flexible in their responses than many of us might appreciate. The author’s experience and knowledge as Emeritus Reader at Keele University and as an Associate of Harvard Forest at Harvard University, USA, shines through in this book, as does his teaching experience, which makes for very clear and comprehensible explanations of often complex subjects. In his career he has covered numerous research topics, from groundwater absorption by roots via seed production to an understanding of tree longevity. In Trees he explores both familiar and unfamiliar species from his wide experience in Europe, North America, the tropics, Australia and Asia, while drawing from even wider fields of recent research. This depth of understanding leads to text that is presented in a clear, entertaining and informative style, bringing to life his subjects.

View this book on the NHBS website

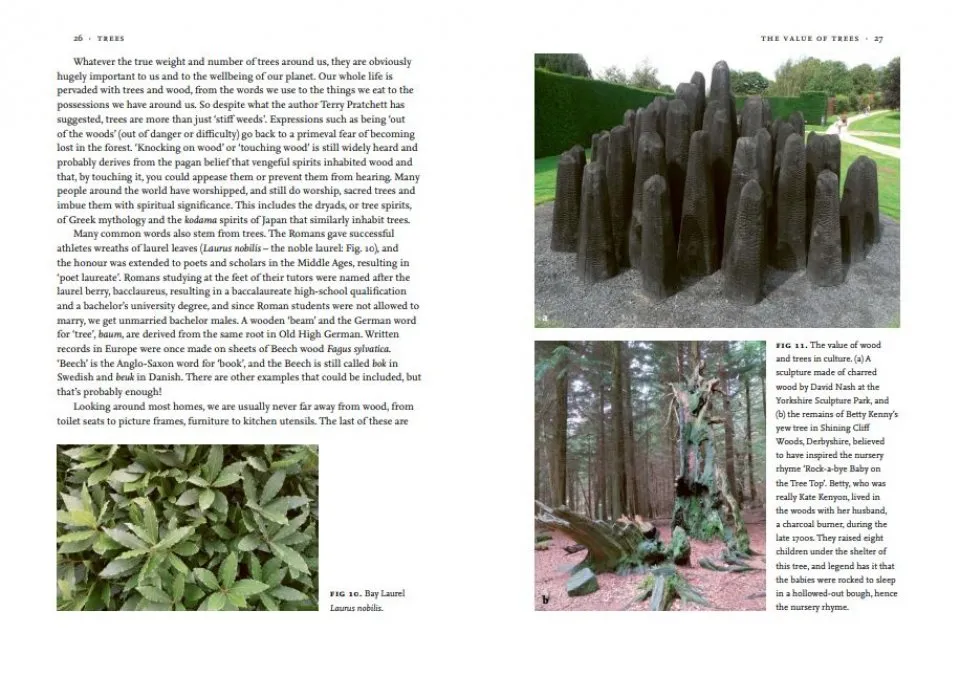

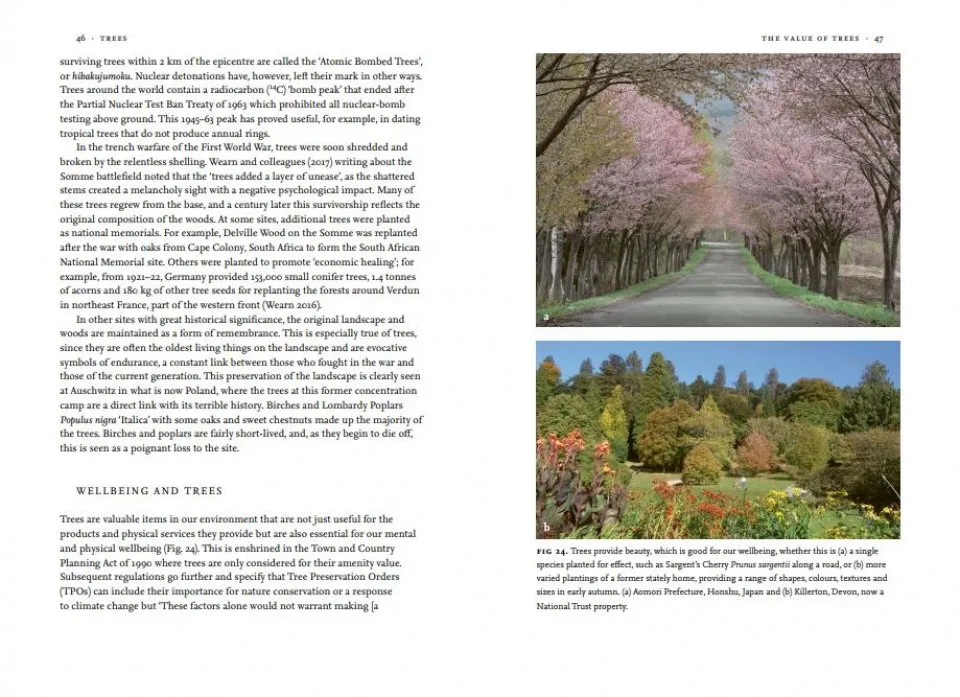

The early chapters cover the basic biology of trees, their functional anatomy, structural engineering, the challenges of water management and distribution, flowering, pollination, seed dispersal, and defence against the ever-growing threats of pathogens, pests and increasingly inclement weather. How trees are organised, and how they organise their growth and performance throughout the year, are explored in full, with many excellent diagrams and photographs chosen to illustrate the problems raised and the points being made. Later chapters deal with the biochemistry of autumn colours, coping with long cold winters and storm damage, the genetics of trees, and their longevity and dendrochronology, along with key chapters on how trees defend themselves against infection and attack and their close association with many other organisms, notably mycorrhizal fungi, tree parasites, climbers, lianas and epiphytes.

Foresters will be especially interested in the chapters on how trees defend themselves against pests, pathogens and damage, while the chapter on tree dispersal, the abundance of tree seeds and the biology of mast years will engage all interested in the natural regeneration of forests for both forestry and nature recovery. The chapter on interactions with other organisms, notably fungal mycorrhizal associations, sheds light on this rather murky and complex subject, and neatly disposes of some of the mystical nonsense about the altruistic nature of trees, their associated fungi and the wood-wide web. The dispersal of nutrients, sugars and the distribution of warning chemicals alerting trees to the presence of pathogens and pests are best described as an uneasy truce while the conditions that favour fair trade persist – it can rapidly collapse when conditions change. The situation is wholly under the control of trees and fungi looking out for their own best interests.

Other chapters cover propagation and tree-breeding, ageing and senescence and threats from cold, fire, wind, drought and water stress. A brief final chapter, ‘Trees and Us’, touches on the benefits that trees provide in the form of carbon storage, pollution control, climate mitigation in cities, and improvements in human wellbeing – along with the challenges posed by roots in urban landscapes. All subjects covered in all chapters are supported by readily accessible numbers – How much water does a tree need? How much sun reaches the forest floor? How many leaves does a tree produce? How much sugar is exchanged with mycorrhizal fungi under different conditions? How close to buildings do trees have to be to cause damage?

Trees is very well illustrated, with both diagrams and photographs presented in an engaging and useful fashion. It is difficult to fault this book (probably because I have been in need of such for so long!) but there are some minor errors… for example, hummingbirds cannot possibly pollinate Australian eucalypts (I think the author knows this and is thinking of Australian honeyeaters, which fill a very similar niche). But it is an excellent and comprehensive book, and highly recommended for all those professionally involved in trees, concerned about trees, or wishing simply to understand more about trees. It will certainly keep me supplied with a sufficient understanding of them for the next 40 years.