This latest New Naturalist is one of the unifying volumes of this venerable series, now in its 76th year and its 143rd volume. Many, if not most, New Naturalists touch on ecology, but none has been devoted to its fundamentals as a science. Funnily enough, no other volume has included ecology in the title either, the preferred term throughout being ‘natural history’. In his chosen title David Wilkinson makes the distinction plain: ecology is science, grounded in theory and experiment. Natural history is observation. Wilkinson is both. He has unusually wide research interests and has also, as it happens, written for British Wildlife on lichens, autumn colours, scents, microbial biology and wildlife in lockdown.

View this book on the NHBS website

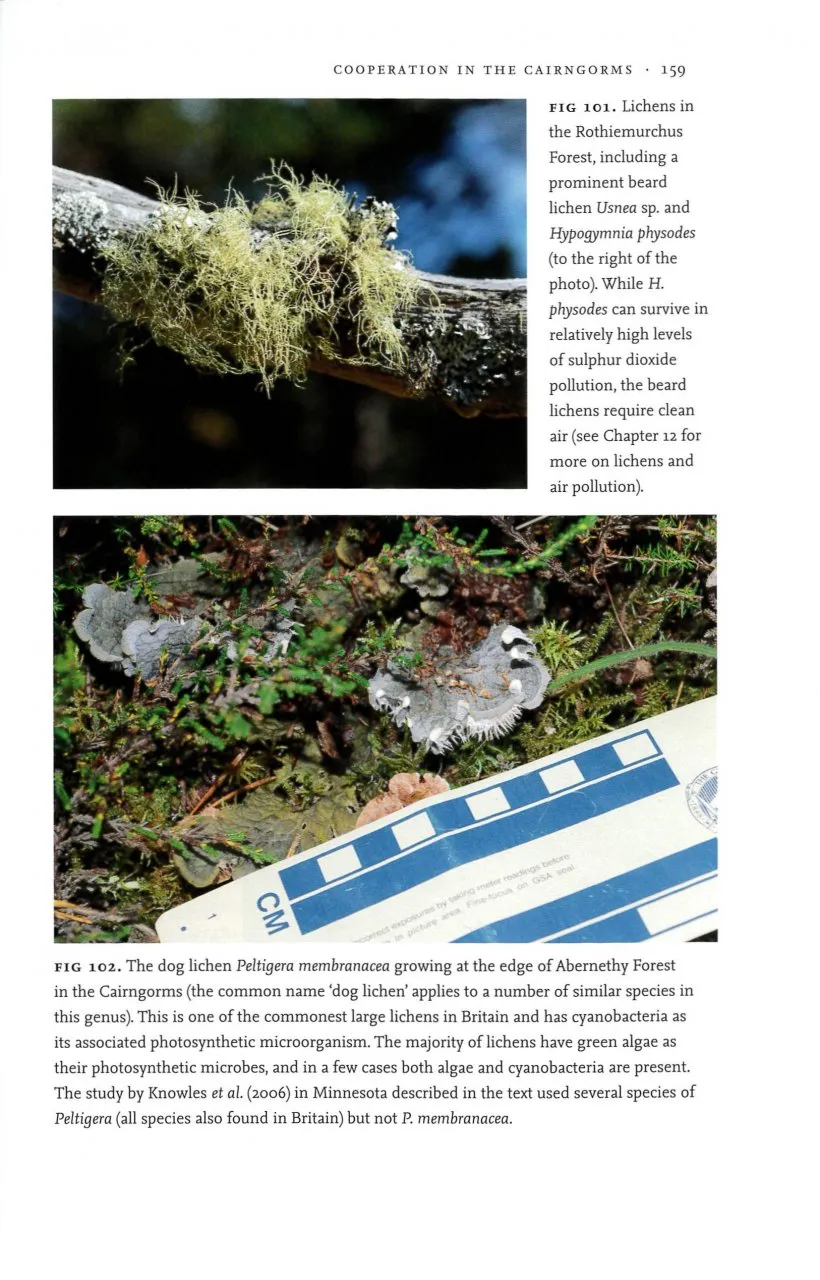

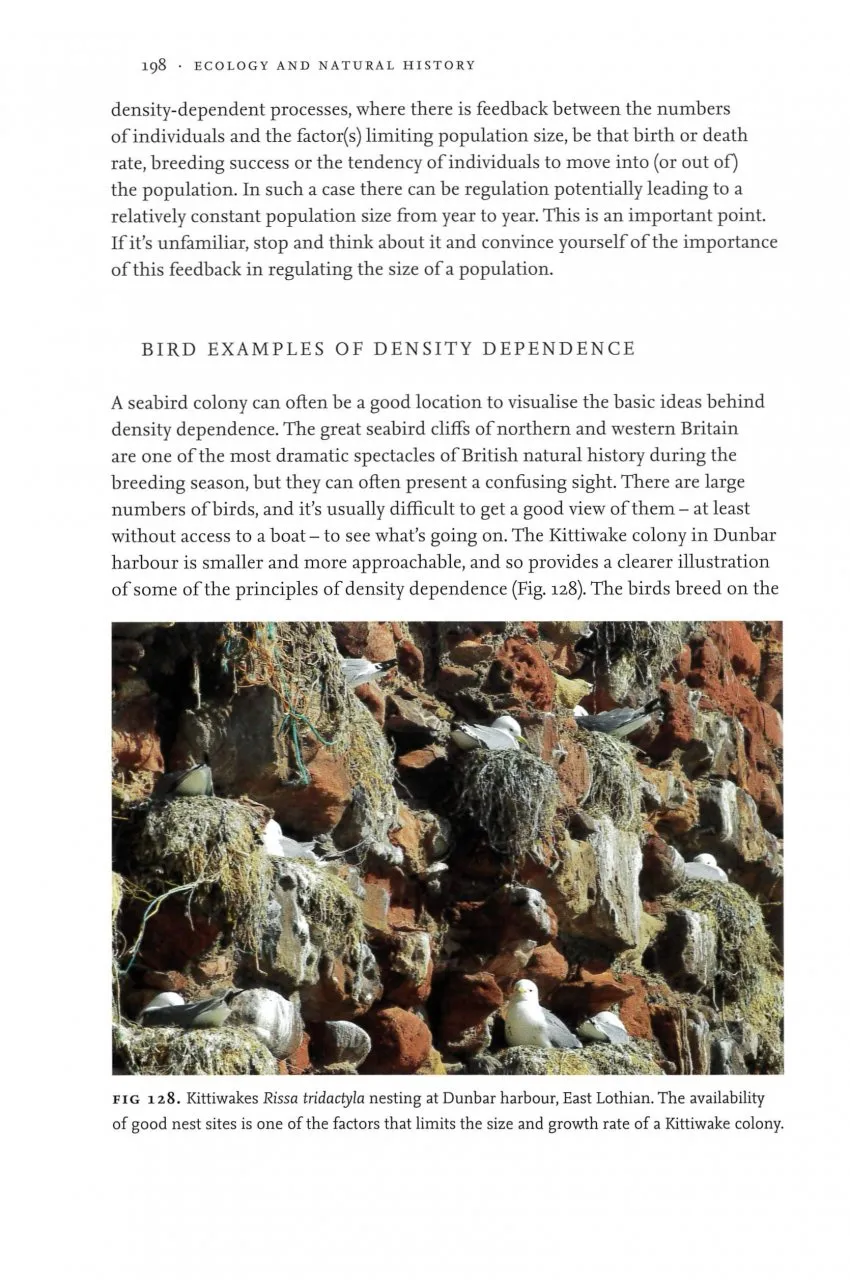

His approach is to introduce the various concepts and processes of ecology by reference to places with a long history of field study. He begins with Downe Bank, Darwin’s orchid bank, to introduce the idea of ‘entangled life’: the multiple relationships between organisms and how they draw energy from their environment in order to live. The following chapter, centred on Cwm Idwal, in North Wales, focuses on the physical (‘abiotic’) and biological nature of a plant’s or animal’s environment. Oxford’s Wytham Wood, probably the most closely studied wood in the world, introduces concepts of photosynthesis, decomposition, carbon storage and, later on, Charles Elton’s idea of the ‘ecological niche’. Lake Windermere brings in ecosystems, nutrient-cycling and then, with a sudden jump, James Lovelock’s ‘Gaia’ hypothesis. Cumbrae, on the Clyde, offers evidence of inter-species competition from barnacles to squirrels. Wicken Fen brings in the concept of succession, while the Cairngorms offers co-operative lives exemplified by lichens and fungal mycorrhizae. The swifts of Selborne help to clarify how numbers are regulated by resources, and bring in the idea of density-dependence. A final chapter centred on Ringlingow Bog, in the Peak District, reminds us that Homo sapiens, too, is ‘an animal embedded in the totality of life’, albeit one with the power to change the world, just as beavers and Sphagnum moss, on a strictly local scale, build and shape their own environment. The application of ecology to such contemporary issues as Covid, rewilding and sustainable agriculture, though emphasised in the blurb, is barely touched on.

Scene-setting helps to make ecology accessible to the general reader. Using examples from British natural history, Wilkinson answers such questions as why there are so many species or how species ‘fit’ their environment without overwhelming the available resources. He seems to be on at least nodding terms with every living thing from familiar birds and beasts to cyanobacteria and testate amoeboids (amoebas that live inside shells). Nearly all the photographs were taken by the author; they are of mixed quality but do the job. The text demands concentration. Although it is clearly written, and eschews mathematics, it is dense with concepts and facts, with a strong whiff of university teaching. It is therefore one of the more technical New Naturalists. But where does it say that nature has to be simple? Its complexity is surely part of its fascination.