A few years ago, it was my privilege to work alongside Natural England’s habitat specialists, looking at what one of them called ‘the fuzzy bits’: the ecotones and mosaics of habitat where nature confounds our attempts to categorise it. Of course, people have always recognised different types of environment and named them ‘wood’, ‘heath’, ‘marsh’ and so on, something that was noted in 1911 by Arthur Tansley, editor of Types of British Vegetation, the first attempt in Britain and Ireland to classify the vegetation that characterises wildlife habitats. Now, a century on, we have an abundance of classifications: Phase 1, Annex I, National Vegetation Classification, and others, each devised for a different purpose. Imperfectly equivalent and often using lengthy, arcane nomenclature, these can be bewildering enough for the professional ecologist, let alone the field naturalist in need of something more succinct to jot down in the notebook.

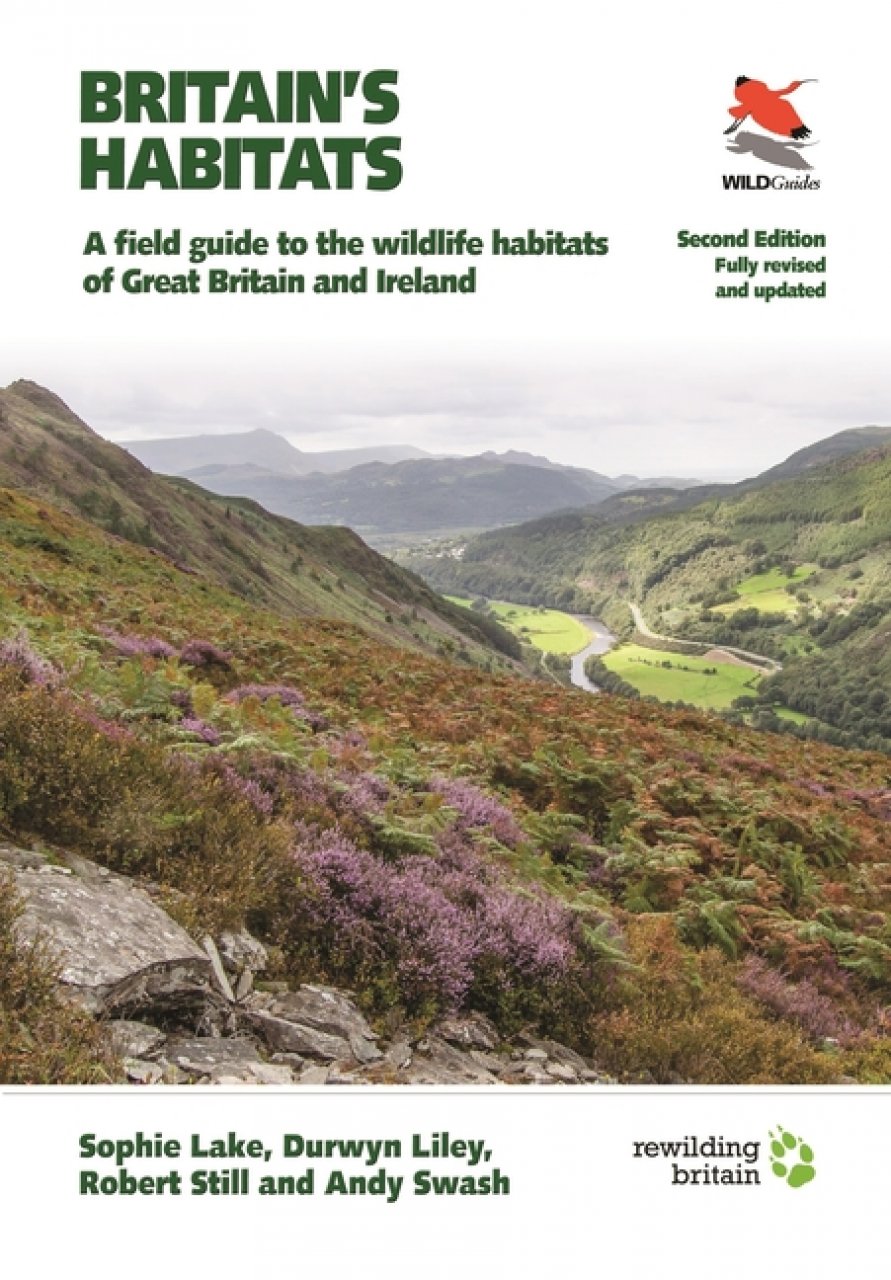

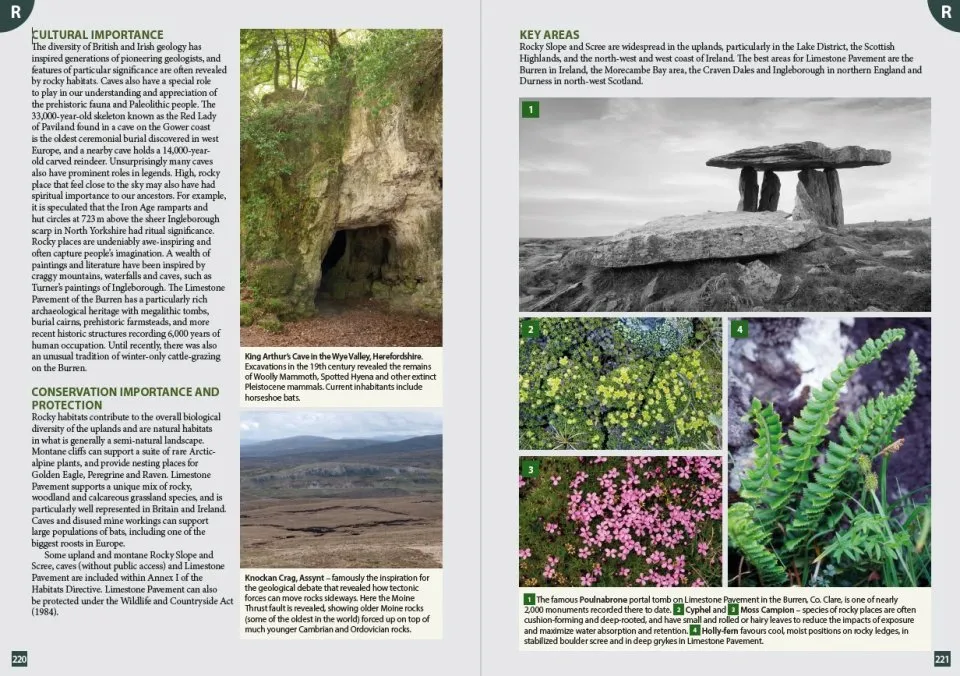

Help arrived in 2015, with the publication of the much-acclaimed Britain’s Habitats. Now in a more compact field-guide format, it provides a concise summary of all the major classifications of terrestrial habitats, and has been updated to include new ones such as the Irish Vegetation Classification. Its attractively shaded correspondence tables show how some of the most commonly used systems relate to each other, and it is almost worth buying for this feature alone. The authors place habitats within ten familiar broad habitat groups, such as woodland, heathland, and wetlands, but even at this scale things can get blurred. Overlaps inevitably occur; does dune heath, for example, belong in coastal habitats or in heathland? The book handles such anomalies well, with good design and cross-referencing. The introductions to each of the broad habitats are comprehensive, including history and cultural importance, and this new edition adds annotated photographs of the key features. In fact, they make ideal primers for anyone new to a particular environment; the coastal habitats pages, for example, are an excellent short introduction to coastal geomorphology and ecology.

View this book on the NHBS website

At the core are 65 accounts of individual habitat types (largely coincident with UK Priority Habitats), which, like the rest of the book, are thorough, well laid-out and richly illustrated. The once-overlooked habitat of Atlantic hazelwoods is included, and ‘garden’ is new to this edition. The accounts have updated maps of a habitat’s distribution, and cover history, conservation and the key species to look out for. At first glance, the ‘how to recognise’ boxes might seem superfluous for some habitats, but it turns out that these contain delightful pen pictures that evoke a sense of what it is like to visit the habitat. Suggestions of when to make that visit are also made. A few habitats, such as juniper scrub and marl lake, do not quite merit their own section and so are covered differently, but, as always in this book, the design makes everything clear.

Unfortunately, any classification, especially when mapped, can give the impression that habitats are fixed with hard boundaries. They then become what entomologist Alan Stubbs has called ‘thinking boxes’ (BW 24: 303), which can blind conservationists to the presence of the fuzzy bits on which so many species depend. The authors are alert to this problem, and remind us in the introductory pages that their habitat types are best thought of as nodes on a continuum. One possible antidote to thinking in boxes is rewilding, which gets a good airing in this new edition. Produced in association with Rewilding Britain, it now includes an introductory section on natural processes and the role of large animals, which complements others on succession and the factors influencing habitats.

Flaws in the book’s production are scarce: the three scrub habitat accounts are missing the reference to their page in the correspondence tables; a few small facts have not been updated; and a tiny number of typos have survived the revision. Otherwise, the book has made the transition to the field-guide format remarkably well. But do we really need a field guide to habitats? Possibly not. I certainly will not be taking my copy into the field. Yet this perhaps misses the point. What this book does is remind the users of other field guides that their organisms of interest do not live in isolation – they are nothing without their habitats. So, make this book an essential companion to your species guides. Read it, enjoy it, take it into the field if that is your need, but do not forget to think outside its boxes: the real world is so much fuzzier.