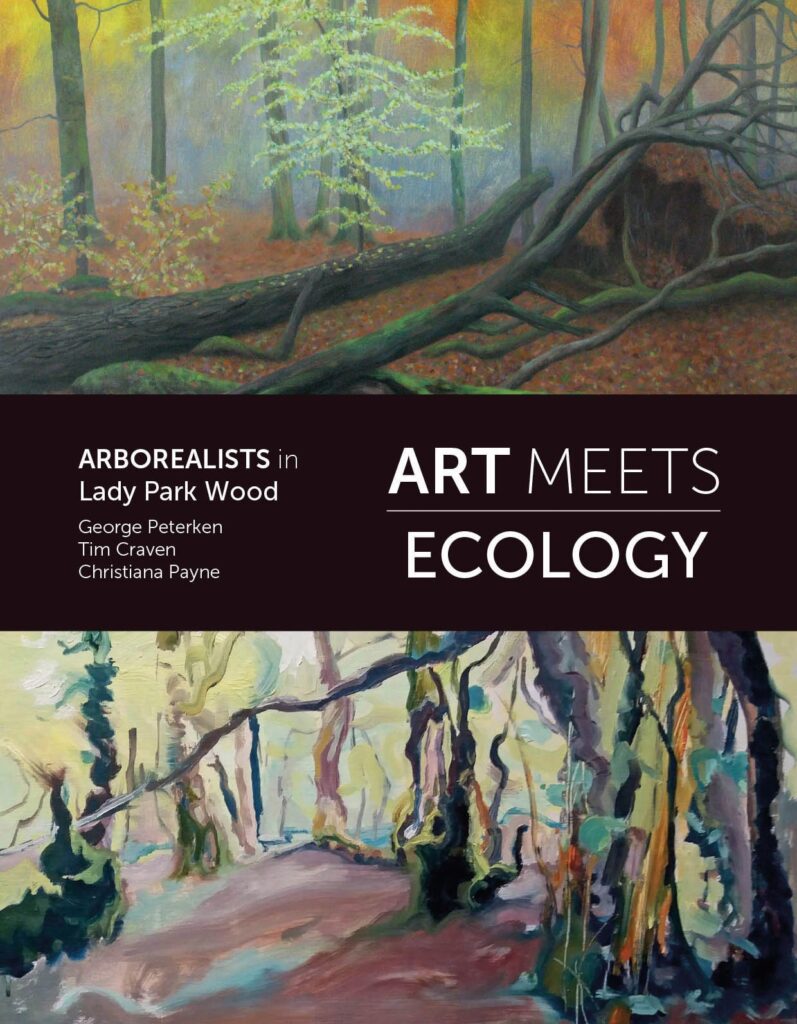

This is something new. A loose-knit group of artists who call themselves the Arborealists have drawn and painted what they saw, and what inspired them, in a steep place in the Wye Valley, called Lady Park Wood. And then George Peterken, a woodland ecologist, has commented on each picture in terms of ‘The nature of the wood, how it works, how it evolved and what it is like to be there’. The effect is like walking through a wood. Both artists and ecologist are close observers of woodland and trees, but express their understanding in different ways: the artists visually, Peterken in terms of his vast experience of natural woodland here and around the world. Two worlds meet and, this time, they harmonise, and meaning is illuminated. Art and ecology are rare and unexpected bedfellows, but it works.

Lady Park Wood is exceptional in that it has been left to nature for the past eighty years. It is also one of the best studied woods in the world, and Peterken has already written a scientific account of the place and what it tells us about natural processes. This time, he does it through the medium of art, which varies from realistic to semi-abstract, and from oil paintings to charcoal drawings, pastels, prints, and even stained-glass designs. Whether or not the artists realised it, each picture tells a story, some facet of the place that encapsulates its nature and history. Trees are rather like people in that they develop character as they grow older. They are also like us in that they are competitors, yet at the same time part of a community: the strong (or the lucky) survive; the weak (or unlucky) go under. Like an ancient city, the wood develops complexity over time: stands of tall trees next to tangles and thickets, ancient stumps, smothers of ivy and clematis, root-plates and logs, and hollows gouged by toppling trunks. Natural woodland is untidy and chaotic. You clamber more than walk, and woods on steep slopes like this one can be positively dangerous (although there is little sense of danger in these pictures).

There is additional complexity in the way we see woodland. Some may look up, others down, most of us straight ahead. One artist saw the wood from the ground up, others painted close-up an individual tree that caught their fancy. One managed to portray the wood in a Turneresque way, in terms of light. Meanwhile, Peterken’s commentary is entirely non-technical and genuinely involving. As he points out, pristine temperate woodland has rarely been painted; he had to turn to North America for examples. While Lady Park Wood is far from pristine, it is wilder than any other English wood, with all that that implies in terms of the effect of storms, droughts, disease and time. From one viewpoint it is a complete mess. From another, that is what makes it interesting: this is nature as it is, not how we might want it to be.

I think that this exceptional collaboration of art and science is genuinely inspired. The book is beautifully printed and laid out. There are artists’ biographies at the end, and a short section on art-history context by Christiana Payne. Publication was made possible through sponsorship and support. We need a name for this sort of art-meets-science, for which woodland makes an ideal template – eco-art, or ‘silviflection’? But, perhaps, after all, arborealism says it best.