In Woodland Flowers Keith Kirby invites us to look at the ‘wood beneath the trees’ and to consider what its flora can tell us. The focus of this, the eighth volume of Bloomsbury’s British Wildlife Collection (which I have contributed to myself), is on the vascular plants of the woodland floor; to this end Kirby embraces ferns as honorary flowers, but for the most part he steps aside from considering other elements of woodland ecosystems (including the ‘lower’ plants, fungi and fauna).

Kirby draws on his lifetime’s study of woodland flora to explore ecological principles, together with the concepts that guide woodland conservation. The species which he considers are therefore the commonplace as well as the rare. This emphasis becomes clear in the index, where brambles (the subject of his doctoral thesis) have 61 entries whereas orchids, of all types, have a mere 26.

View this book on the NHBS website

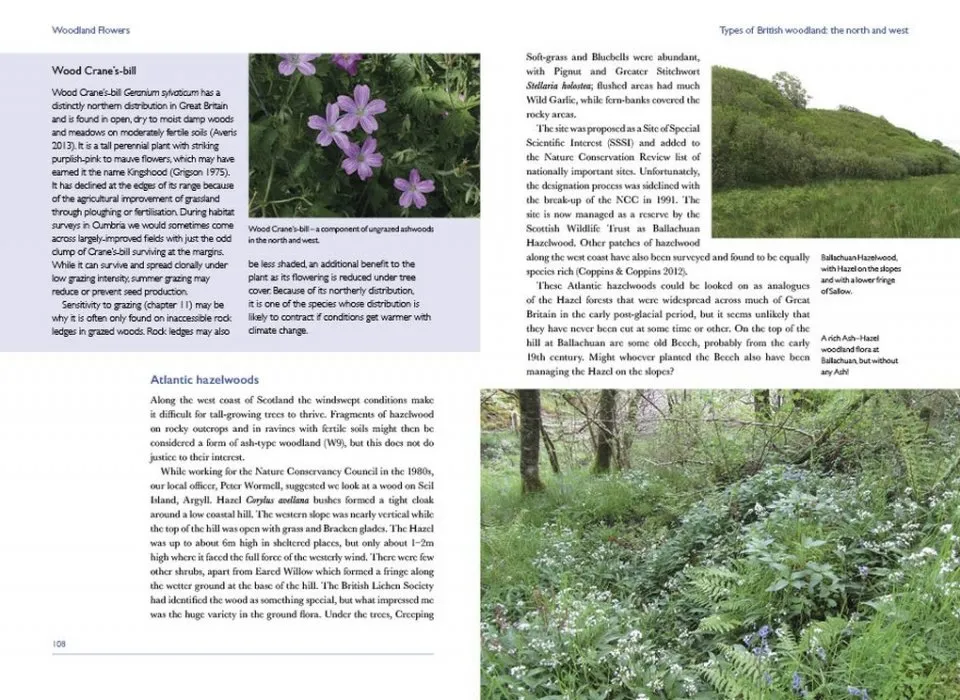

In the opening chapters, the reader is guided through definitions of ancient woodland and ancient-woodland indicator species. Kirby dissects these ideas and points out where they may assist decision-making, but also notes the perils of applying them thoughtlessly. A suite of species that are indicative of a long continuity of woodland in one part of Britain may be unhelpful in another. The concepts of woodland sites and species become fuzzy once one leaves the conveniently compartmentalised landscapes of the British lowlands.

The National Vegetation Classification provides a useful means for Kirby to explore variation across Britain and the biogeography of woodland plants. Inevitably this is ‘big picture’ stuff and only occasionally does he divert into the discussion of exceptional localities. Britain’s woodlands are set in a broader Eurasian context in the entertainingly titled chapter ‘Woodland plants across the channels’, including the pointed subtitle ‘We are part of Europe’.

These opening chapters are a helpful, non-technical exploration of the work of British ecologists, including John Rodwell, Oliver Rackham and George Peterken (Kirby’s predecessor at the Nature Conservancy Council), along with our European and Irish neighbours. The book then becomes much more stimulating, even provocative, as Kirby explores the relationship of woodland floras with the modern age.

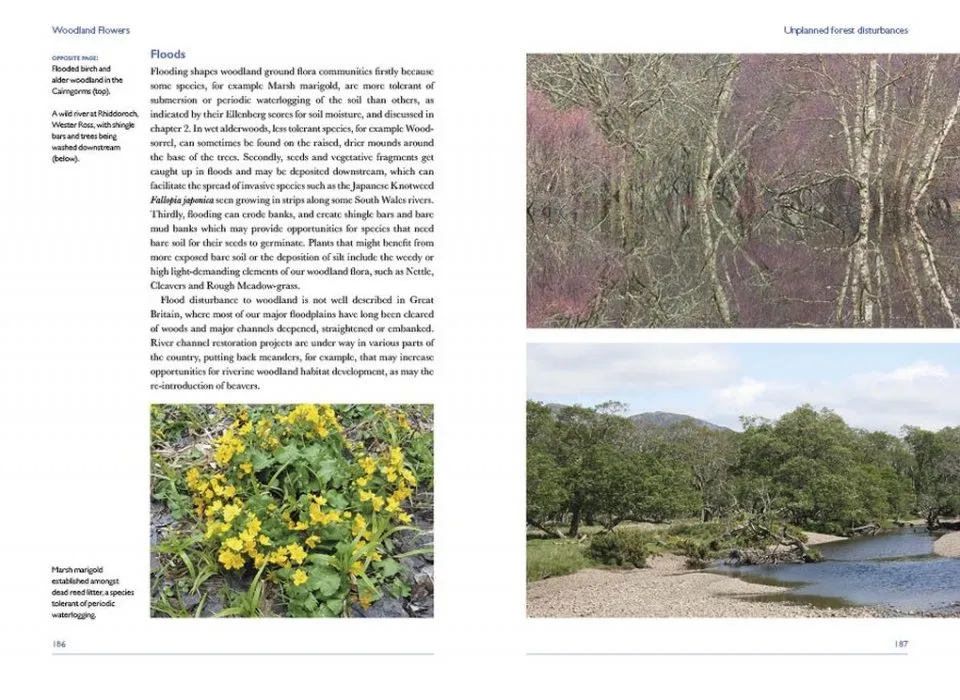

There are factors that affect woodlands which arise from external forces, notably climate change, aerial pollution and the changing nature of manufacturing, with woodland products supplanted by hydrocarbon fuels, steel and plastics. There are then factors over which society has a more direct control, notably in the subsidies that we make available to woodland-owners and the retention of a nationalised timber industry in the form of the Forestry Commission. Kirby offers a detached account of the consequences of coniferisation of ancient woods at the public’s expense. In an equally objective manner he comments on recent trends in replacing conifer plantations with broadleaf trees and their subsequent management as continuous high-canopy forests. Such forestry regimes are gentler on the native flora than are pure conifers, even though the surviving flowers may be manifest as ‘a thin scatter of woebegone-looking plants’. Had this analysis included other woodland species, notably the specialist organisms of old-growth trees, or the invertebrate communities reliant on a continuity of early-stage ecological successions, then the prognosis may have been harsher. There is still a long way to go to reconcile the aspirations of timber-growers with the conservation of Britain’s woodland wildlife.

Kirby is unfashionably reticent about embracing the theories of Frans Vera and other advocates of large herbivores in natural (or at least near-natural) ecosystems. This is healthy, well-expressed scepticism and helps to counter uncritical group-thinking. Kirby’s caution may yet stimulate more research into the natural niches of our native wildlife in wooded landscapes.

I hope that Kirby’s exploration of continuous-cover forestry, along with many other issues, stimulates further debate on the relationship of tree-planting and timber production with nature conservation. While Kirby recognises the ability of generalist woodland plants to colonise new plantations, he also recognises that the enlarging and connecting of woodlands may diminish the integrity of important open habitats.

There is much to enjoy in Keith Kirby’s writing style as his language is straightforward and accessible. As you progress through the chapters there are quotations and lightly concealed allusions to verses from the English folk-song tradition. In drawing his book to a close, Kirby comes clean and admits to a youthful enthusiasm for nights in the pub, roaring out songs about fox-hunting, whaling and the glory of war, while being heartily opposed to such practices. Through this extended metaphor he cautions us against binding ourselves to a mythical ‘authentic folk voice’ and neglecting the evolving scene of today.