This features contributions from leading academics in the field of hedgerow ecology, although many also have a practical knowledge of management.

It is stated in a preamble that there are two main sections. The first deals with definitions, current and historical management, the impact of pesticides, and the decline of hedge stock and condition, together with new approaches to hedge evaluation using remote-sensing techniques. Chapters reviewing the importance of hedges and margins to lowland wildlife, in particular those by Phil Wilson, Joanna Staley and colleagues, emphasise not only the inherent value of structure, connectivity and provision of food resources but also the huge negative effects that such practices as over-frequent cutting can have on species such as Brown Hairstreak Thecla betulae and fruit- and seed-eating birds in the winter. A chapter on the application of remote sensing demonstrates how useful and revealing technology such as satellite data and Lidar can be. While these may be beyond the means of individuals and small organisations, the authors explain that even aerial ‘photography’ can be used to good effect.

View this book on the NHBS website

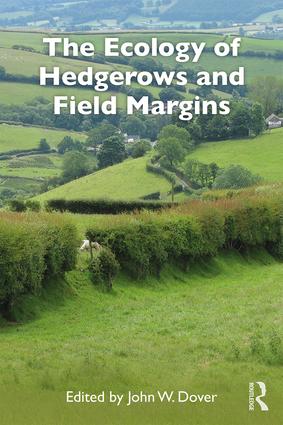

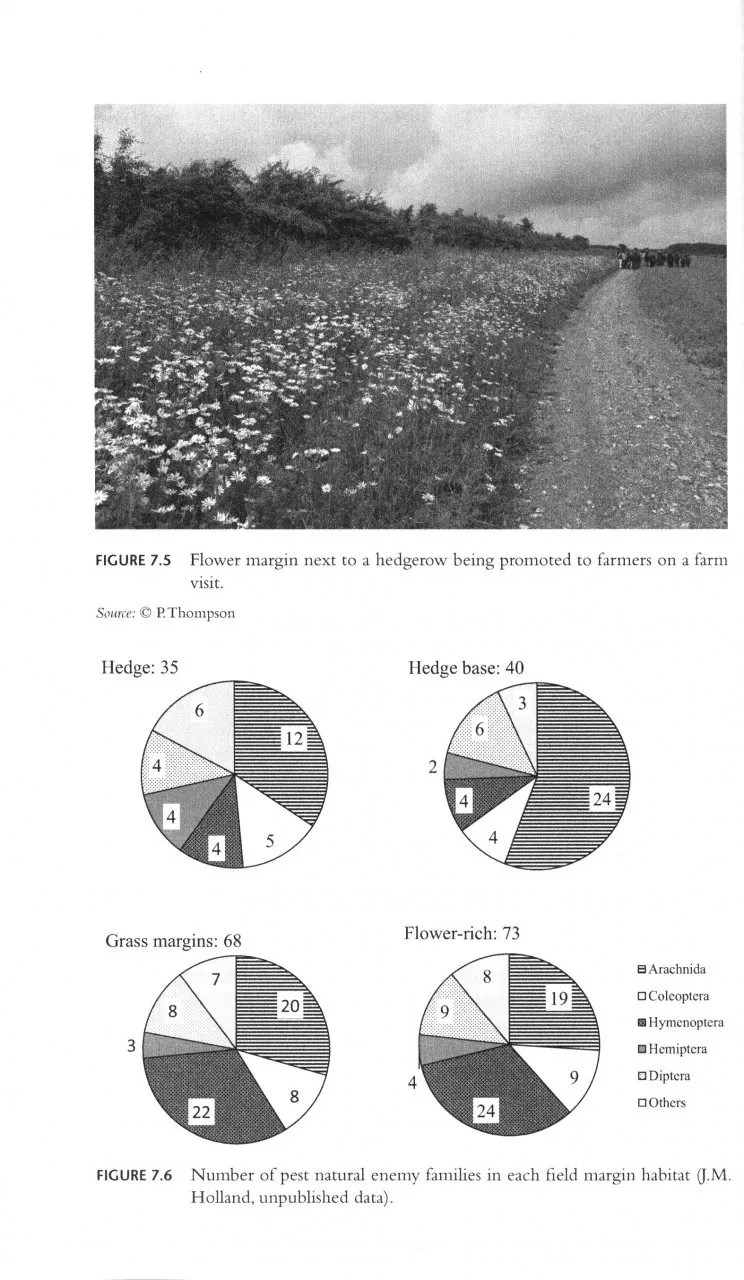

The second section reviews the pollination and biological pest-control benefits provided by hedges and field margins and continues to look at the major taxonomic groups involved. The clear deleterious effects of accidental or careless application of pesticides, including neonicotinoids, on non-target habitats and species are discussed, setting the scene for chapters on practical conservation management programmes. I found two of these to be of particular interest, as I believe that they provide stand-out examples of applying research findings in the field. The first, written by Nick Sotherton, is on Conservation Headlands, which were developed as a measure to arrest the decline of the Grey Partridge Perdix perdix by increasing the availability of invertebrate prey. The second, by Chris Stoate, is on the Allerton Research project, at Loddington, which has been dedicated to researching methods for improving the farmed environment for biodiversity and incorporating requisite management from these findings. A following chapter reinforces the value of these two projects with a summary of how sensitively managed hedgerows can significantly aid biological control of crop pests.

Two chapters, one on carabids and another on pollinators, present data from detailed research projects which demonstrate that the role of hedgerows as conservation and ecosystem-services ‘tools’ are highly complex and in truth still relatively poorly understood.

The final part of the book has a series of chapters on taxonomic groups that are strongly associated with hedgerows and field margins, including butterflies and moths, birds and mammals, and ends with an overview of the biodiversity value of urban hedges. The broad conclusion here is that, for all groups, hedgerow ‘quality’, as measured by habitat components and elements such as landscape connectivity, is vital.

My only gripe with the book is the order of the chapters. It is sometimes difficult to assign a theme to individual reference-book chapters but I would have preferred that they were grouped a bit more logically: for instance, starting with biodiversity topics as the first section to emphasise the importance of hedgerows as a habitat, then ‘putting the knowledge into practice’ section to follow, and finally the chapter on remote sensing. Nevertheless, every chapter pretty much stands alone as a fine piece of reference work, and one can dip in and out anywhere and be sure to learn something.