The folklore of plants was a dead subject brought back to life first by Geoffrey Grigson’s evergreen The Englishman’s Flora (1955), and then by Richard Mabey’s best-selling Flora Britannica (1996). The present doorstep of a book by Roy Vickery, a botanist formerly at the Natural History Museum, makes it a trilogy, a varied and minutely detailed record of our informal relationship with plants, past and present. But this is a different kind of book from its two predecessors. It lacks the lyrical grace of Grigson and Mabey, in which each entry is in effect an essay. Instead, it is a tabulation that focuses on the ‘folk’, i.e. the communal stories and beliefs, as opposed to those of individuals. Vickery notes, modestly, that his tome is ‘by no means definitive’, and hopes that other folk floras will emerge, but he has been collecting material since the mid-1970s from more than 2,160 contributors. I suspect that it is about as definitive as we are going to get.

Vickery’s approach is that of an archivist. He does not go in for much social analysis or context. He is less interested in the ancient heraldry and meaning of the English rose, for instance, than in its adoption by the Labour Party, and in the wearing of white roses after the murder of Jo Cox MP and the Grenfell Tower disaster. Plants make infinitely flexible symbols, and embody beliefs that are often contradictory. Some say that the planting of Rosemary will make you friends, others that it is unlucky (lots of plants are lucky, and lots more are unlucky). Picking Primroses might help the chickens to hatch, but may also risk a death in the family. Flowering gorse should never be brought indoors, but it is perfectly safe to burn it on the kitchen range. At least some of these stories make a kind of sense. The terrible hag Jenny Greenteeth, who lives under the duckweed and will pull you in and drown you, is a warning in the style of Heinrich Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter or Hilaire Belloc’s Cautionary Tales. Do not tread on duckweed or you will go under. The less well-known Melsh Dick, another of these ‘nursery bogies’, will give you bother if you eat unripe Hazel nuts. The nuts will, too.

View this book on the NHBS website

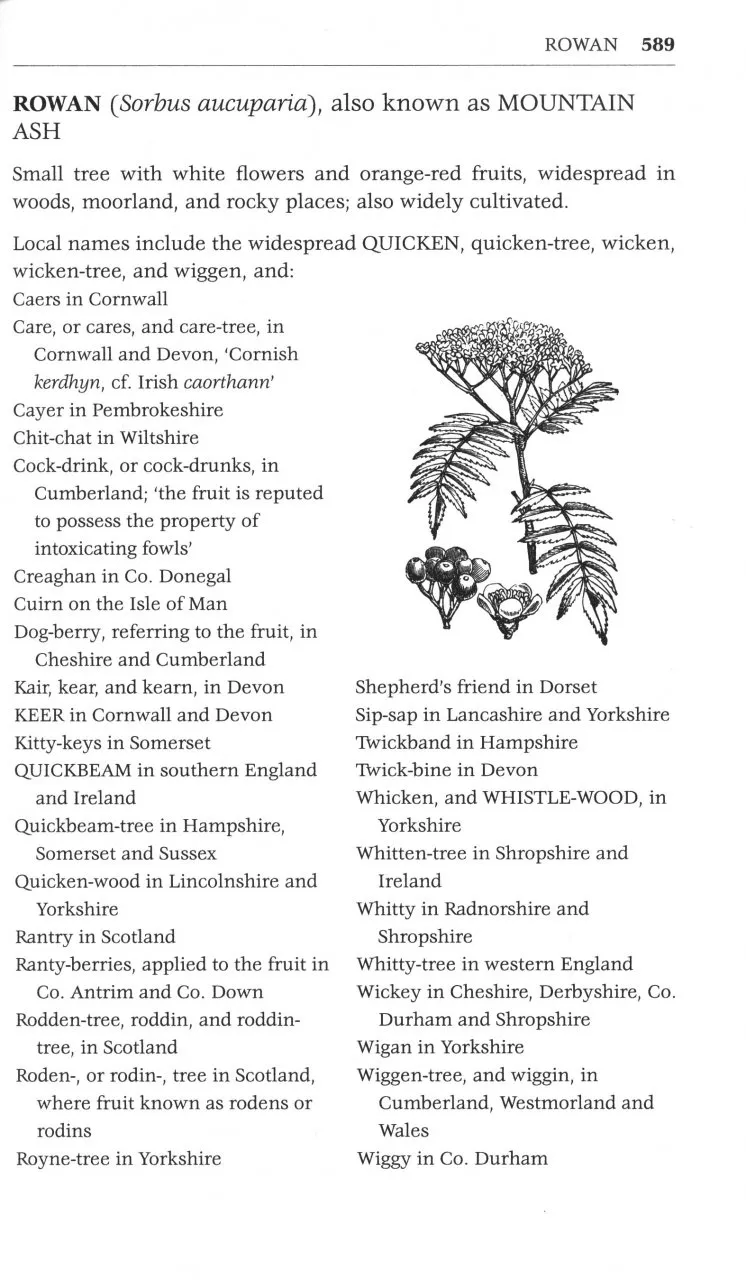

Vickery includes both wild and garden flowers, as well as fruit, vegetables, nuts and herbs, and, indeed, any plant which has gathered folklore about it as part of its identity. He also includes trees, which are some of the longest accounts in the books – oak, Ash, apple, Elder, Horse Chestnut and hawthorn, but not Beech, which keeps a surprisingly low profile in this world. If a plant has no folklore it is not included, and that rules out all the species which only botanists could recognise. All the same, it does include some less common or easily missed plants such as Adder’s-tongue (good for healing the inflamed udders of cows), or Royal Fern (‘bog onion’) or Alpine Meadow-rue (picked to make a dye in Shetland).

It would probably be disastrous to use this book to identify wild food, or even for useful information. It is more a record of what we used to believe, and to some extent still believe. It says at least as much about us as about plants and botany: in our stubborn insistencies, in our imaginative journeying and in the lore learned on mother’s lap. On this evidence we seem to be curious, practical, irrational, superstitious, cautious, humorous, providentially minded, occasionally fearful and sometimes bawdy. We seem to love symbols, search for meanings in nature, and let our imaginations run wild. Above all, we Brits and Irish have a gift for names. The common names of our wild flowers enrich the language, but Vickery sets out numberless alternatives, many of them still in use locally. Had fate been different, our waysides would be brightened by lady-lords, sampers, crannicks, penny-johns, bozzums and beltanefloers.

This is a book for browsing. A lot of browsing. It is well set out, with two slim blocks of colour plates in the middle and a picture of the thickly bearded author gazing warily from the back flap. It is fully referenced with a 21-page bibliography and a 72-page plant-name index. It is £30 well spent.