It is now 65 years since Ospreys first returned to Scotland to nest and for much of that time the population remained in a relatively small area, but today we can celebrate the fact that Ospreys breed in all three of the British countries and in Ireland. The population has now risen to around 300 pairs, so it is a good time to revel in the success of this species.

This latest Poyser monograph is by Tim Mackrill, who has made Ospreys a major focus in his life, spending many years working with them at Rutland Water and helping to coordinate monitoring of the birds when they reach West Africa in the autumn. He has also advised on Osprey introductions elsewhere in Britain.

The book looks at every aspect of the birds’ lives, including hunting, dispersal, nesting, migration and survival. With the author’s involvement at Rutland Water, there is an appendix detailing breeding attempts there from 2001 to 2022, and there is also a list of key viewing sites around Britain.

View this book on the NHBS website

Remembering that the Osprey is one of only six landbird species that occur on every continent except Antarctica, there is a huge set of references from around the world. There are also 150 colour photographs, plus maps and charts.

Ospreys are so impressive. Watching one dive into a lake from up to 40m, one can only marvel at their skill, but we learn that the angle of this dive may be adjusted according to the type of fish being caught. In addition, Ospreys can move their toes in a different manner from that of other raptors, enabling them to provide a better grip on captured fish. They are also adaptable with their diet, and our British birds take freshwater fish in lakes during the summer and then willingly switch to exclusively saltwater fish in West Africa in winter.

Young Ospreys first return to breed in their third calendar year, males usually breeding closer to their natal area than females. The age of first breeding is usually lower in expanding colonies as there is less competition for mates and nests. Once settled, however, they show a high degree of fidelity, and they may breed together for ten years or more. Interference at nests from non-breeders can reduce productivity and this is observed mostly when populations are close to carrying capacity.

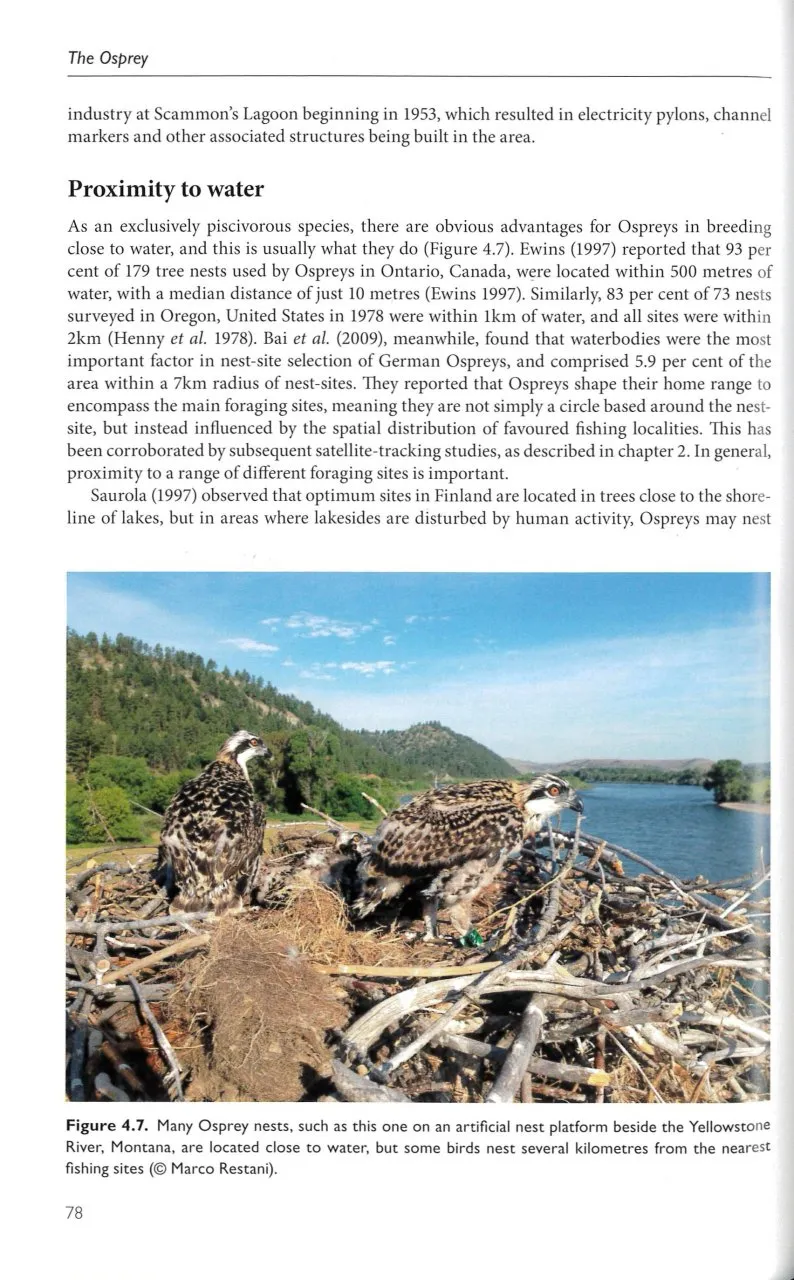

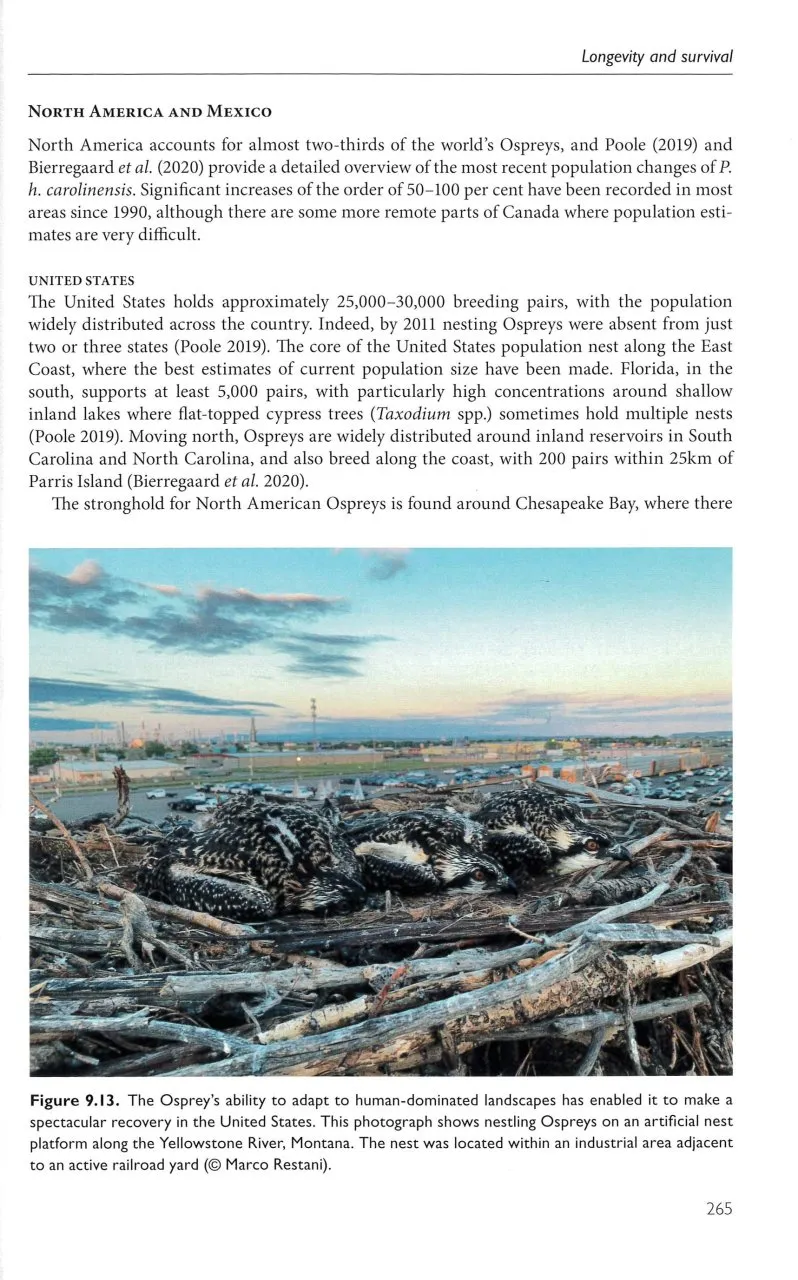

In the UK and Ireland, Ospreys usually select either an isolated or very tall flat-topped tree for nesting. Around the world, however, many other structures are used, including electricity pylons and phone masts, and with recent introduction schemes they have readily accepted human-made nests. In much of Europe Ospreys breed at low density, but in North America they occur in much higher concentrations; in Florida there are even cases of more than one pair nesting in the same tree!

After the breeding season the female departs first, followed by the chicks and then the male. Because they migrate alone, juveniles follow an inherited programme of direction and distance to reach their wintering destination. This is known as vector summation and is one of many elements of Osprey migration that we do not fully understand, such as whether they learn to recognise landmarks or use other methods to achieve accuracy.

Although the author’s own experience is based on British Ospreys, he has drawn in plenty of material from around the world. For example, birds from eastern Russia migrate south to coastal Arabia, the Indian subcontinent and South-east Asia, while most North American Ospreys winter in Central or South America. The distances travelled by populations vary: some birds will travel as far as 8,500km, while those that breed closer to the equator may move little or no distance. In Europe, however, there is a growing trend for Ospreys to winter in Iberia – and, given that the highest mortality of juvenile birds occurs when crossing deserts such as the Sahara, this makes sense. Having completed their migration to wintering grounds, juveniles are often forced into poorer-quality areas, which also increases mortality. Once the adults return to their breeding grounds, however, the young Ospreys stay put and so have an opportunity to develop their own hunting areas.

One subject I had not appreciated is just how badly Ospreys were persecuted in the past owing to their exploitation of fishponds. The killing of Ospreys was actively encouraged by the paying of bounties until legislation prevented this. The introduction of organochlorine insecticides in the mid-20th century, however, led to eggshell thinning in Europe and North America. More recently, research has identified the flame retardants used in textiles as a potential emerging threat to Ospreys. Rather than degrade over time, these accumulate and enter the food chain, and this is an urgent area for future research.

Today, the Osprey is celebrated as an emblem of conservation success. The first translocations of chicks to rebuild the populations were in North America, in 1979. The Rutland Water project started in 1996 and was the first of its kind in Europe. Other projects have followed elsewhere in Britain, and in Spain, Italy, Portugal, Switzerland and France. Your chances of seeing an Osprey flying over are now greater than at any time in living memory. Not only is this book well constructed and engagingly written, but it is also very timely.