Britain may be one of the least wooded countries in Europe, yet woodlands occupy a special place in our culture and affections. Our relationships with woodland and trees are multidimensional and far from static. People are fiercely protective of them: witness the successful protests against privatisation of state forests 12 years ago and, sadly, the less successful attempts to prevent the huge destruction wrought by HS2. Woodlands even have their own high-profile, mass-membership conservation NGO, which cannot be said of other habitat types. George Peterken has written a multi-layered book about British woodland that is hugely informative, laced with insights and opinions, and superbly illustrated with carefully chosen photographs, most of which were taken by himself.

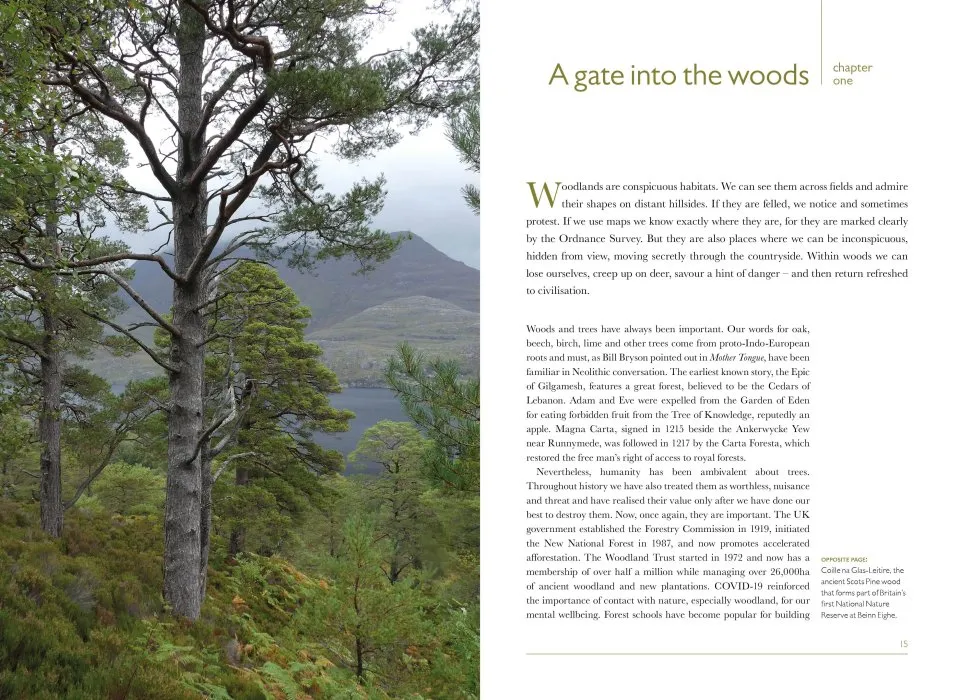

Few, if any, people can match Peterken’s knowledge of the woodlands of Britain built over a long career embracing intertwined strands of research, conservation and forestry. After a PhD spent working in the New Forest, he joined the staff of the much-lamented Monks Wood Experimental Station, the spirit of which is echoed in the dedication. He then became the woodland specialist of the Nature Conservancy Council within Derek Ratcliffe’s Chief Scientist Team. These posts gave him latitude to explore, survey and compare woods throughout Britain. This personal experience permeates the pages; you know that he has spent time in the many featured places and thought about why they have come to be the way they are now.

View this book on the NHBS website

The focus is firmly on native trees in semi-natural woodland, both ancient and recent. It is suggested that forest plantations deserve a book in their own right, but nonetheless non-native conifers are not entirely neglected. For the sake of completeness, a chapter on conifer plantations would have been welcome, especially as once more we find ourselves in a period of forest expansion. From a book containing so much, three broad messages remain foremost in my mind: (i) the individuality of both trees and woods, (ii) change within woodland is constant but often random and not readily predictable, and (iii) the material and non-material values that people place on woodland are varied and ever-evolving.

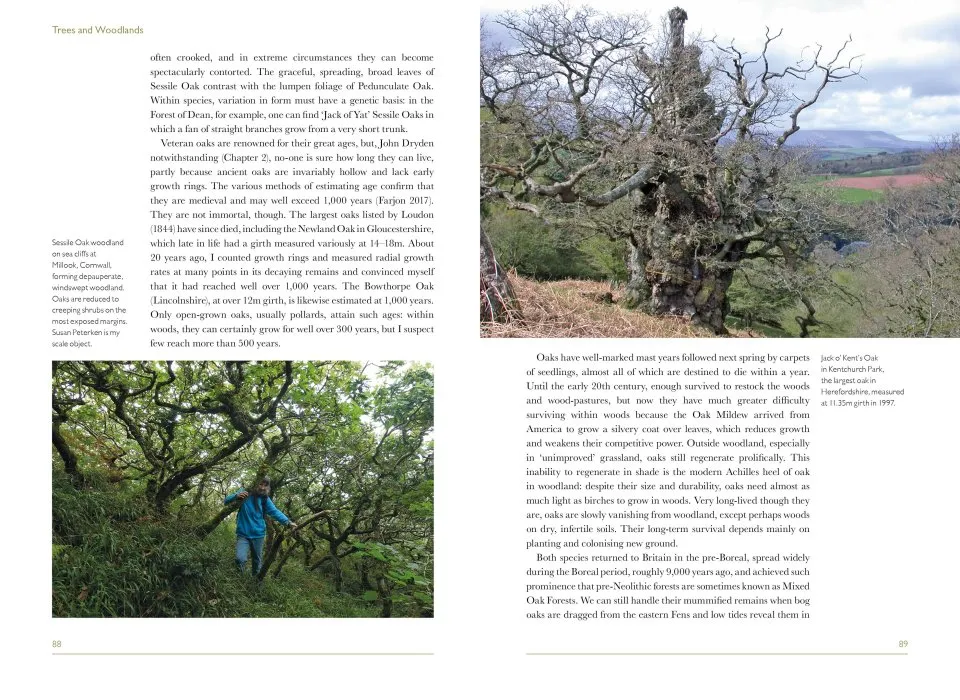

The diverse forms, character and ecological associations of trees and shrubs within woodland are brought out very clearly in three of the early chapters. An excellent summary is also given of woodland types and their broad distribution in Britain based mainly on tree-species composition, though the limitations and dangers of fitting woods into neat categories are well appreciated. Peterken is interested primarily in how woods change and develop over time, both through natural processes and human modification. The question of what happens to woodland when left to its own devices is explored, drawing on his own work in Lady Park Wood in the Wye Valley. His ideas of what constitutes natural woodland are refreshing and pragmatic, recognising the reality of ubiquitous human influences. As one would expect, the overwhelming importance of historical and ongoing activities of people in shaping what we see today recurs throughout the book. We are perhaps most familiar with this in the lowlands, where pasturage, coppicing and plantation management have all left their obvious mark. I was less aware of the extent to which the planting of oak in many western areas has transformed what was previously mixed broadleaves or wood-pasture.

Part of the appeal of this book is that it does not confine itself to ecological and historical aspects. One senses that Peterken himself has been ever broadening his own perspectives, now taking a keen interest in the associated art and literature – I greatly enjoyed the penultimate chapter on trees and woodland as rich sources of cultural inspiration.

The book contains many interesting views about recent issues and trends affecting woodlands. Here is a selection, hopefully not too distorted by oversimplification. In the future he believes that we should be retaining what we have, especially ancient woods, seeking to reverse fragmentation and improve connectivity between woods. Two habitat types should be priorities for restoration: treeline woods and floodplain woodland. The latter habitat features prominently in the book and, because most of it was destroyed so long ago, it is scarcely possible to know which of our poplars and willows are truly native. It is argued that a degree of acceptance of introduced tree species is desirable (in the right places). Many are developing ‘a natural ecology’ in Britain with self-sustaining populations, even raising the prospect of ‘facsimiles of the Pacific Northwest rainforest’ composed of mixtures of magnificent conifers. Regarding rewilding, Peterken’s preference is to see most woodlands managed. He is, however, supportive of the various shades of rewilding making an important contribution to woodland expansion, and he sees that rewilding can potentially offer complementary habitats to traditionally managed nature reserves. He advocates establishing more ‘reference woods’ where natural processes are permitted to proceed without intervention; these should be in stands of introduced trees as well as mixtures of native trees. As for Ash Dieback, given the genetic variation within the tree and its capacity for prodigious fruiting, Peterken urges us not to panic and to avoid unnecessary felling. He strongly questions the wisdom of introducing tree species thought likely to perform better than native species based on assumptions about how future climate might change.

The book is a timely reminder of the enormous diversity of British woodland types and of the need to respect the individuality of the woods themselves. The intricate variation and complexity of our semi-natural woods are so well expressed and added much nuance to what I thought I already knew. It reinforces that slightly uncomfortable feeling that generalisations in conservation and ecology often need to be received with caution.