Heathland is the second title by Clive Chatters in the British Wildlife Collection, after Saltmarsh (2017). It takes a broadly similar approach to its predecessor, beginning with the basics – what heathlands are, where they come from and where they are situated, and their various sub-habitats like bogs, tracks, ponds and streams. The bulk of the book takes us on a tour of Britain’s heaths, from St Martin’s in Scilly and the Lizard in Cornwall all the way to Unst in Shetland. The final section offers changing perceptions of heathland down the ages and Chatters’ ‘vision’ for heaths in the future.

He takes an unusually broad view of heathland, taking in not only the familiar heather-covered heaths of southern England, but also the grass heaths of the Culm measures and the Breck, rocky Atlantic heaths from St Davids and the Lleyn in Wales to Assynt in north-west Scotland, the coastal heaths of north-east Scotland, at Forvie, Coul and the Black Isle, and the odd patches which are all that is left of the heaths in the Midlands and Lincolnshire. All these examples are places which the author knows and loves. There is also a chapter ‘in memoriam’ for the lost heaths at Hounslow and Constable Country in Suffolk. It reminds us that heathland was once widespread in Britain; nearly every county had its marginal commons and wastes, places of poor, often sandy soil which resisted agriculture until the 19th century. The fragmented heaths of today (like poor Bartley Heath in Hampshire, ‘partly heath, mostly motorway’) are only ‘pale shadows of their former selves’.

View this book on the NHBS website

This is a holistic exploration of heathland, taking in history, vegetation, characteristic plants, animals and insects, and usage, past and present. I imagine that there are not many other writers who could broach with equal authority the literature on heaths from Chaucer to Hardy; the lives of the rural poor; the misuse and obliteration of heaths from enclosure, afforestation and wild fires; the physical nature of heaths compounded of rock, water and vegetation; and, not least, the animals and plants that live there. In Chatters’ hands we are not confined to familiar Dartford Warblers and Sand Lizards, but such quiet beings as Basil-thyme Case-bearer, Splachnum, the moss that mimics the smell of fresh dung, and the lost Alpine Butterwort.

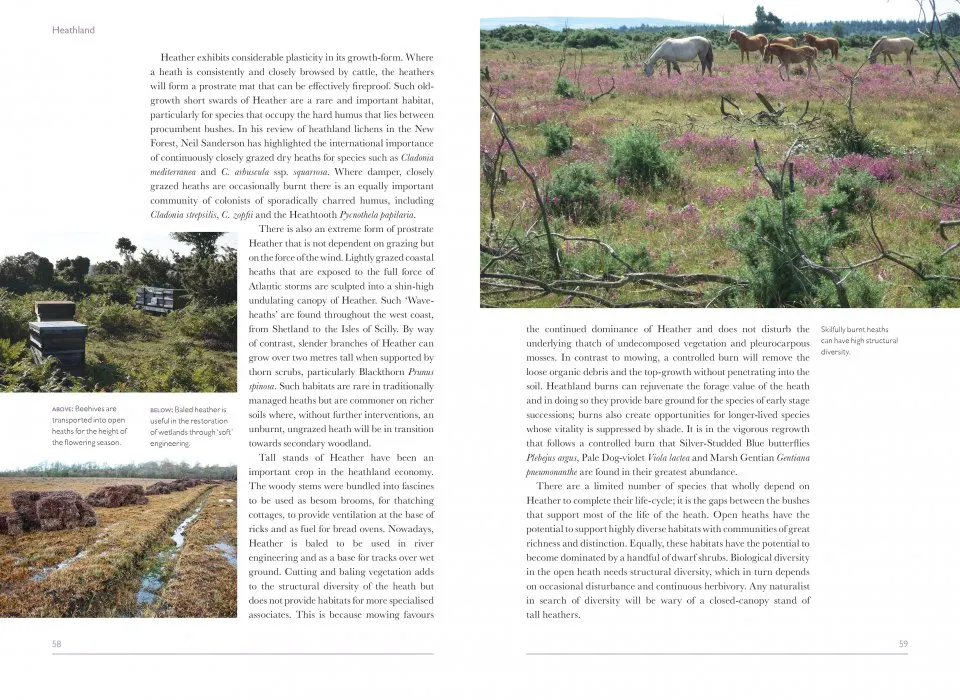

Heathland is highly readable, and especially enjoyable if you know some of these places. Chatters presents evidence for his view that heaths in their original form are among our most natural habitats, kept in being by grazing and browsing. In prehistoric times they were maintained by deer, horses, wild cattle and pigs. Low-intensity grazing by their domestic proxies maintains their biodiversity, but can be hard to arrange unless the heaths are large enough, and this is the key. Without grazing, heaths shed species and the smaller they are the greater the loss. Chatters is cautiously optimistic about the future of heathland in Britain (‘should we wish’), so long as we can connect the scattered pieces and revitalise them by reinstating their historic use. Heathlands transcend narrow nature-conservation aims: they are natural landscapes, or, as Chatters expresses it, ‘biological manifestations of our relationships with the land’.

He has written an ecological masterpiece, generous in its sympathies, awe-inspiring in its breadth of knowledge, and genuinely enticing in its journey around heathland Britain. This is a book that ought to influence policy. As always in this series, the illustrations and design are top class.