I first encountered Merlin Sheldrake in Robert Macfarlane’s 2019 book Underland, where he inhabits a chapter about the web of connections within forest soils like a sort of eloquent Puck with a PhD in tropical ecology. He was born, I read, during the Great Storm of 15th–16th October 1987. I remember that morning well, the step-change in the way the world felt – we had difficulty in getting to school through the arboreal carnage, the broken walls and vehicles. It was an exhibition of nature’s power that unsettled and thrilled me. How strange and satisfying, then, that a book by a boy born that very night should do the same.

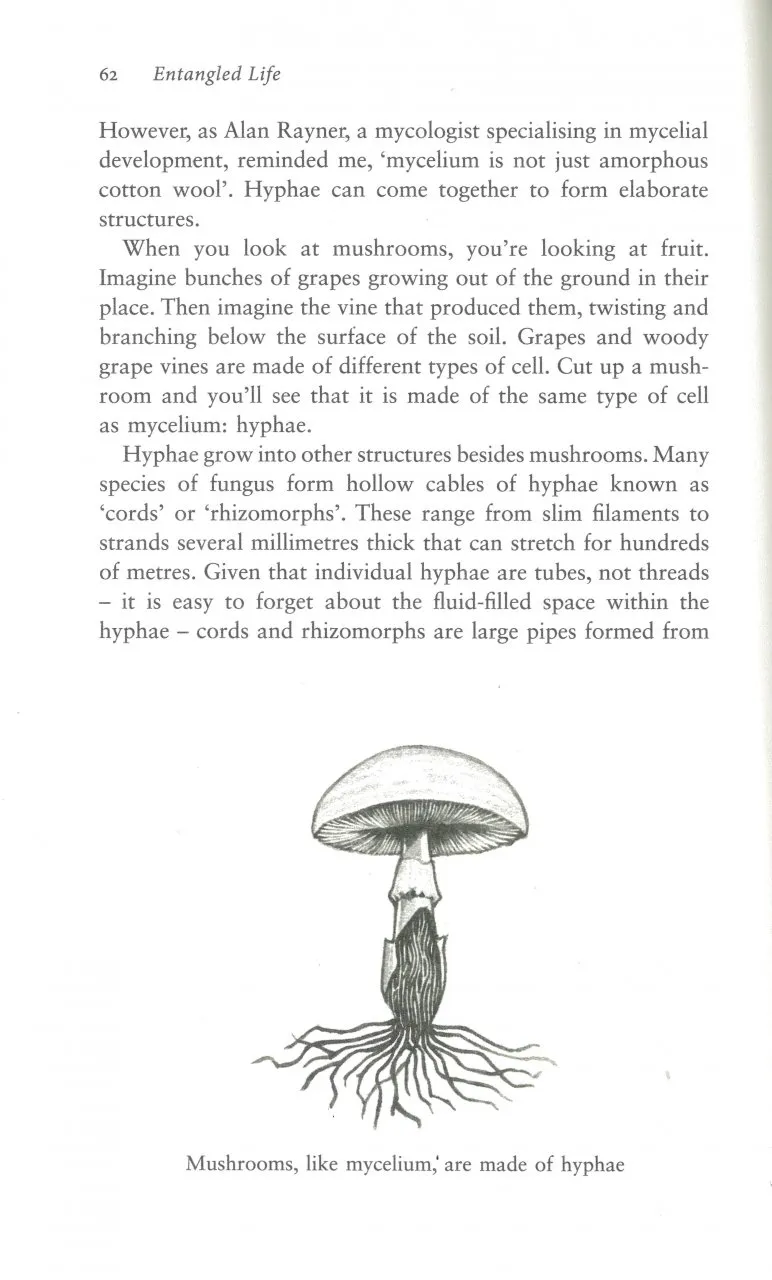

Sheldrake became a student of woodland ecologist Oliver Rackham, then turned his attention to symbiotic mutualisms – and particularly to those between plants and fungi, which include lichens and mycorrhizal associations. It ought to be common knowledge now that nature nurses us in a web of connection so dense and intricate we cannot view ourselves as separate. The more attentive already realise that the material from which that mesh is woven is largely fungal – or, more accurately, it is mycelial. Mycelia are the networks of microscopic hyphal threads which most fungi comprise, most of the time. There are kilometres of hyphae in a teaspoon of healthy soil.

View this book on the NHBS website

This is Sheldrake’s first book, and, while his expertise means that the readers should feel that they are in safe hands from the off, in truth the experience is more like being whisked down a burrow by a white rabbit, or on a tour of Willy Wonka’s research facility: a trippy, astonishing, and completely exhilarating ride.

Wonders come thick and fast. Explosively discharged fungal spores accelerate 10,000 times faster than a space shuttle at launch and fill the atmosphere with half a million blue-whales-worth of material a year. Fungi nursed plant life on to land more than 400 million years ago, and those early land plants may have ‘learned to do roots’ from the mycorrhizas on which they were already dependent. Fungal networks provide the means for plants to communicate and share resources, like the original Internet of Things, while trading nutrients by using ‘buy low, sell high’ strategies more familiar on stock exchanges. The mutual relationships formed between fungi and other life forms are so intimate that they shatter most concepts of what makes an individual. Fungi can turn living animals into zombie-robots – species of Ophiocordyceps infect and control the bodies of carpenter ants and thereby gain an ability to perform behaviours beyond their own physical capabilities – to climb to a position above the forest floor with perfect temperature and humidity for spore germination before clamping on to leaf veins to ensure a flow of nutrient and then putting out a fruiting stalk that sprinkles spores down on to more hapless ants below. It is a form of extended phenotype whose deviousness is secondary only to its gothic grandeur. Oh, yes, and in their spare time fungal spores make weather and slime moulds solve mazes.

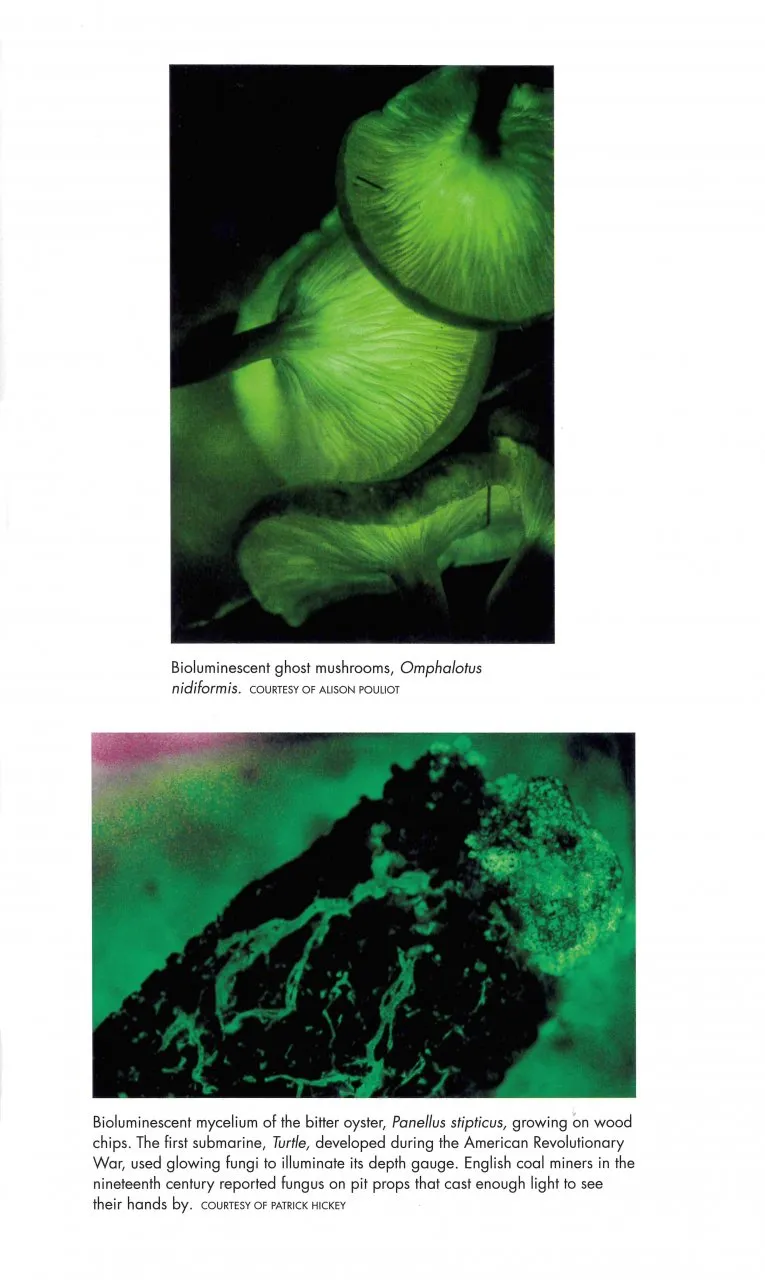

Even the more familiar fungi – those whose mushrooms we eat – have astonishing powers, some of which might help to fix our many mistakes. Fungi can be trained to metabolise spilled crude oil, toxic dyes, synthetic hormones, pesticides including glyphosate and chlorophenols, antibiotics and medical and veterinary drugs, and even DMMP, a neurotoxin used in VX gas. Not only can they survive massive doses of radiation (the first living organism to sprout in the atomic blast zone of Hiroshima was a mushroom), but some can actually eat it – a whole community of radio-trophic fungi now thrives in the ruined reactor at Chernobyl. They can convert waste, including used nappies and cigarette butts, into food that we can eat and into a vast range of materials that we can literally build a future with.

The vibe of the book echoes the effects of psilocybins, the psychoactive compounds found in some fungi that profoundly alter the experience of being. We fly by the hypothesis that consumption of these mind-altering mushies may have played a part in the evolution of human language and creativity. Again and again we glimpse vistas of wonder that border on pseudoscience, and every time we are pulled back on to more empirical rails, wide-eyed and breathless, experiencing a kind of biological vertigo where not only humankind, but all of animal-kind is ancillary to the big picture.

These insights and questions are backed up with 80 pages of notes and references, making the book a feat of collation and synthesis as well as a masterpiece of exposition and enlightenment – all the more extraordinary given that Sheldrake has just turned 33. I lost count of the times I exclaimed out loud, drew and puffed a long breath, reread passages to make sure that I was not imagining too much. Once I got up and danced. This book is likely to change the way you see everything, without having to eat a single magic ‘shroom. Go on, it cannot hurt to try a little bite.