I cannot think of a better place to bring people into close contact with nature than a rocky shore. Most visitors are soon searching rockpools for small fish, crabs and prawns and are captivated, even if they first had to be dragged there by their children. John Archer-Thomson and Julian Cremona have both spent many years in taking school and university students and the general public into this fascinating environment. I wish that I had been one of the latter, because the ability of these authors to communicate in a lively and memorable way shines out clearly in this beautifully written book. They state that their aim was to produce an accessible guide to rocky shores. Without a doubt they have done this. The book is a worthy addition to Bloomsbury’s British Wildlife Collection series.

The first chapter explains what rocky shores are and where they occur around Britain and Ireland. I much enjoyed their descriptive tour, which takes the reader on a journey around our coasts, though I would contest that East Anglia is bereft of any rocky shores – there is a small one at West Runton! This section is an excellent resource for planning a trip and, having myself done Hebridean shore surveys, I would thoroughly agree with their assessment of Islay as an excellent juxtaposition of delightful rocky shores and equally delightful small whisky distilleries.

The second chapter (Patterns and Zones) provides an excellent overview of the zonation and patterns of distribution of rocky-seashore denizens. This is one of the most fascinating ecological aspects of any rocky shore and is fundamental to what lives where and why. I can think of few, if any, other habitats that are subject to such dramatic changes in living conditions each day. Chapter three is devoted entirely to rock pools, arguably the most important microhabitat on rocky shores and decidedly the biggest draw for people. I thought that I knew my rock-pool flora and fauna, but I did not realise that some chironomid midge larvae are regular and abundant inhabitants. Very few insects can survive submergence in seawater, but Clunio marinus larvae live there perfectly happily, providing an important food resource for rock-pool fish and other creatures.

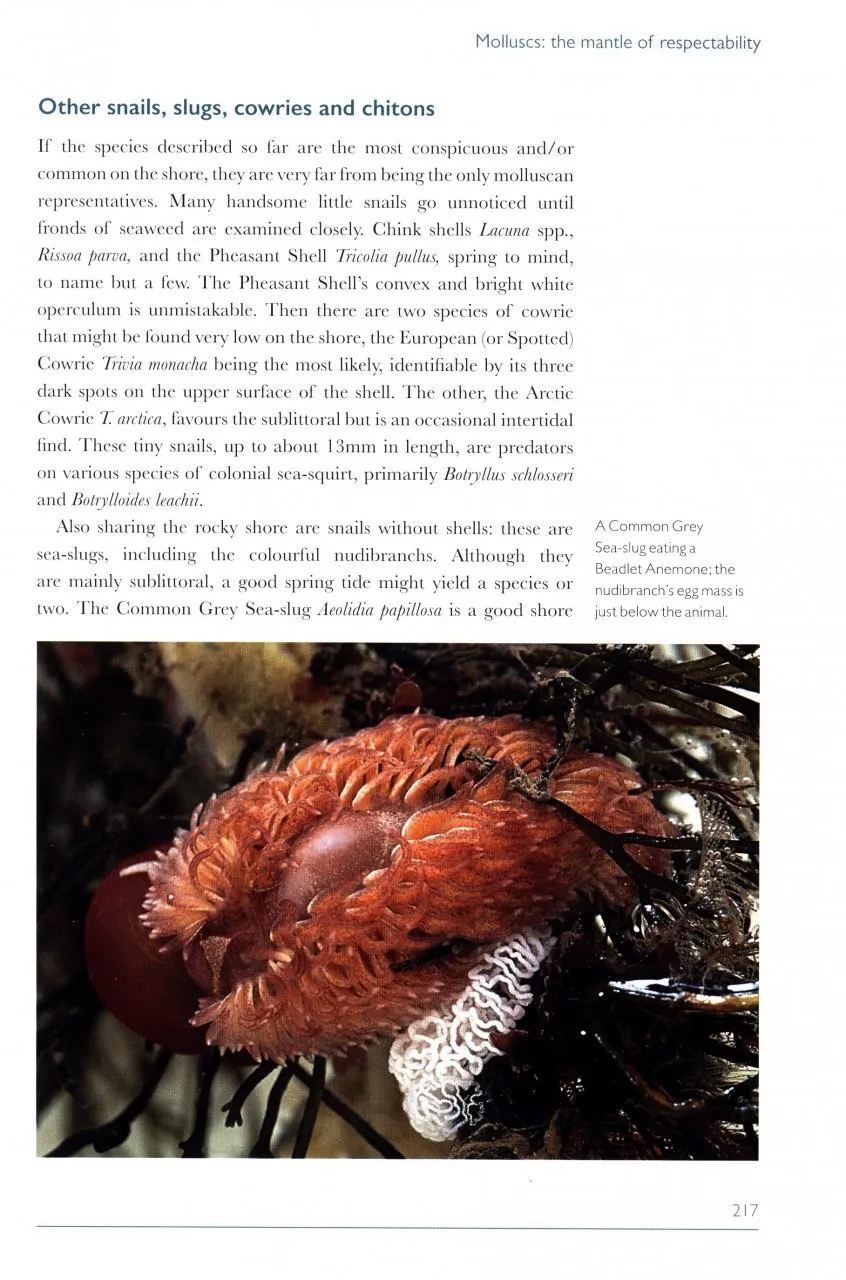

The next eight chapters describe the huge biodiversity of rocky-shore inhabitants, with chapters on lichens, seaweeds and plankton, as well as animal phyla from sponges and other blobby, squishy and wriggling things (one chapter on stingers, squirts, sponges, mats and worms), through molluscs, arthropods (insects, arachnids and crustaceans) and echinoderms, to the vertebrates (mammals, birds and fishes). Each chapter provides a fascinating overview of just what each type of creature is, what they do, and how and where they live and survive. Commonly encountered species are used as examples, along with others that require a bit more searching, such as the tiny pseudoscorpion Neobisium maritimum. These chapters are where the ‘accessible text’ really shines through. Reading the section on periwinkles, for example, has not instantly made me an expert, but it has told me which ones I can and cannot distinguish in situ and where I might find them, and provided fascinating information on their ecology and life history.

View this book on the NHBS website

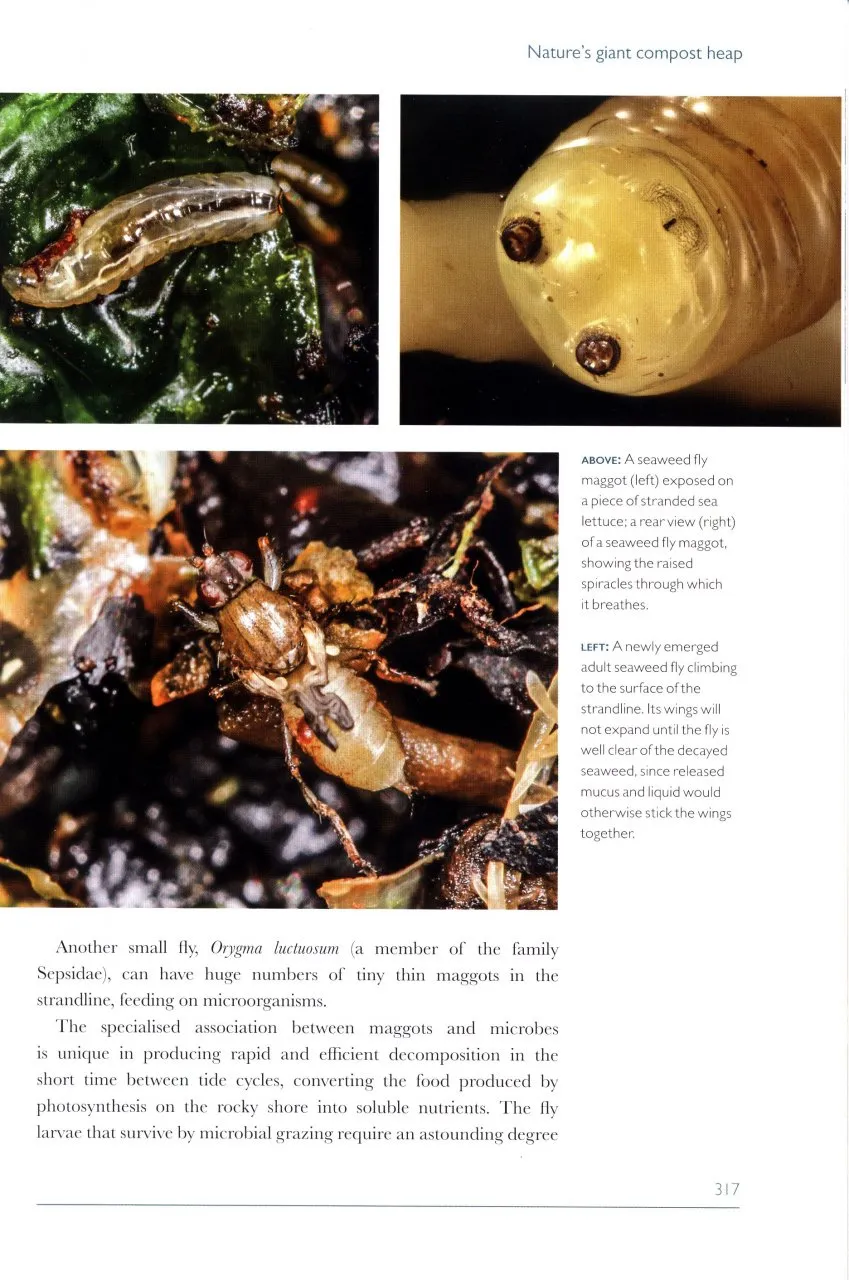

The penultimate chapter will help all those who enjoy beachcombing and presents an account of the importance of strandlines – vital breakdown factories, which supply quantities of mostly seaweed-derived particulate detritus and nutrients into the seawater (something that civically proud authorities often fail to appreciate). The final chapter covers some of the threats that rocky (and other) shores face. The authors also highlight the importance of data collection and records, explaining how the data on the size and numbers of limpets, collected over many years by their students, suddenly became extremely relevant as pre-oil-spill information when the Sea Empress spilt crude oil over ‘their’ rocky shores.

It is obvious that almost all the material included in the book comes from the two authors’ personal experience. In fact, the authors state this in their preface, and it really does make this a ‘living’ and lively book. They also include plenty of relevant material taken from recent research, and a knowledge and appreciation of local history is apparent throughout the book, which gives an added dimension and interest.

A well-known English-language idiom is that ‘A picture is worth a thousand words’. I find, though, that books with an emphasis on glossy photographs, without enough information, are very frustrating. In Rocky Shores, however, the layout of the text and photographs is excellent. The quality, size and number of photographs allow the reader to ‘get the picture’ and understand concepts such as vertical zonation or the mass march of Spider Crabs Maja squinado. The text is further clarified by a number of graphs and diagrams, used sparingly and effectively to illustrate specific points, such as temperature variation on the shore.

My future visits to rocky shores will be greatly enhanced by reading this book. Do I have any criticisms? No, not really – this is a book to enjoy as well as to learn from.