This is the newest addition to the excellent series published by Pisces, which, among other regions, has previously covered the Wyre Forest (2015), the Malverns (2018) and the Somerset Coast (2022). Like those titles, it is lavishly illustrated and focused on the area’s special plants, animals and invertebrates. It is written by Clive Chatters, who has lived in the Forest for forty years and has been involved with its conservation throughout that time, initially with the then Nature Conservancy Council and the Hampshire Wildlife Trust. He helped to set up the New Forest National Park and more recently sits on the Court of Verderers, which regulates grazing on the common. He probably knows the Forest and its wildlife better than anyone and is an experienced and critical natural history writer. Not surprisingly then, this is a very good book.

It is not a portrait of the National Park (which has wider boundaries) but of the Open Forest, that is, the common land, grazed by ponies and cattle, and the inclosures made into it, around 30,500ha in all, making the New Forest easily the largest common in lowland England. This ‘Forest’, which, as Chatters reminds us, is a legal term, not a habitat, consists mainly of heath and pasture woodland, with natural grasslands and various wet bits, from streams to puddles, and including the foreshore of the Solent. The overall point is that the Open Forest is a dynamic ecosystem, grazed by free-ranging animals owned by commoners. We are more used to nature reserves that are micromanaged according to a plan. Here, by contrast, nature is essentially unplanned; the animals make the decisions where to graze and at what times. Is the Forest overgrazed, as some believe? In part it depends on which wildlife you mean. For woodland butterflies it is overgrazed, but for many other insects it is not. Natural regeneration is patchy, but probably adequate in recruitment terms. Some of the Forest’s epic biodiversity, including rarities, depends on periodic disturbance: eroding tracks, muddy gateways, sand and marl pits, and even puddles.

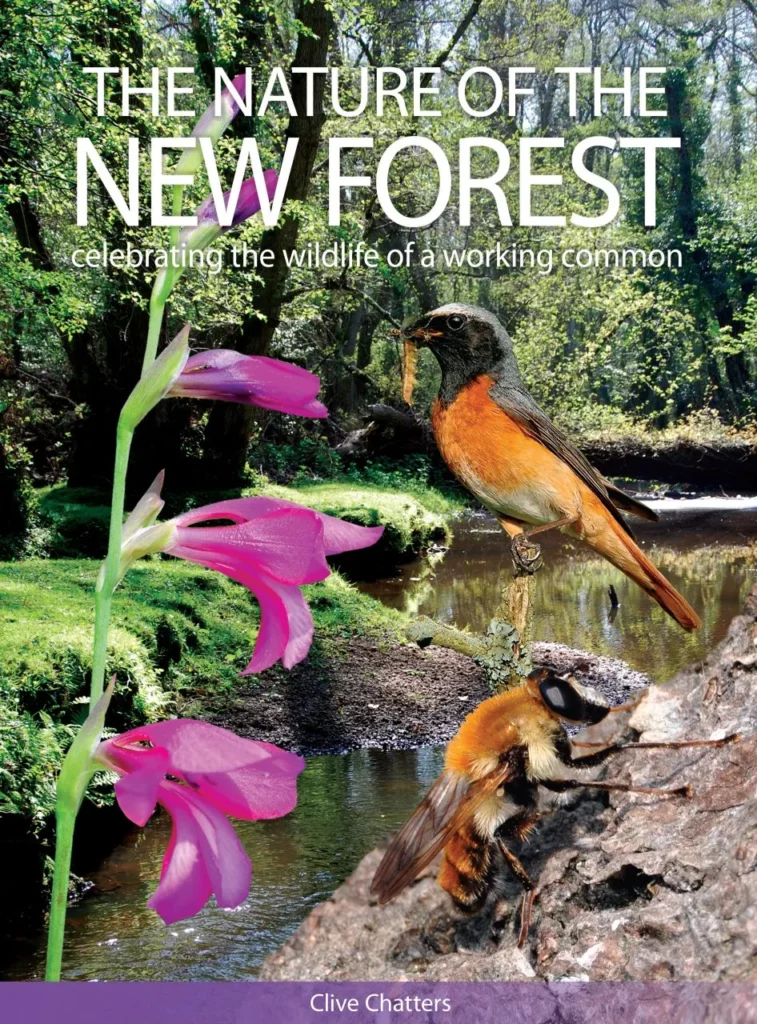

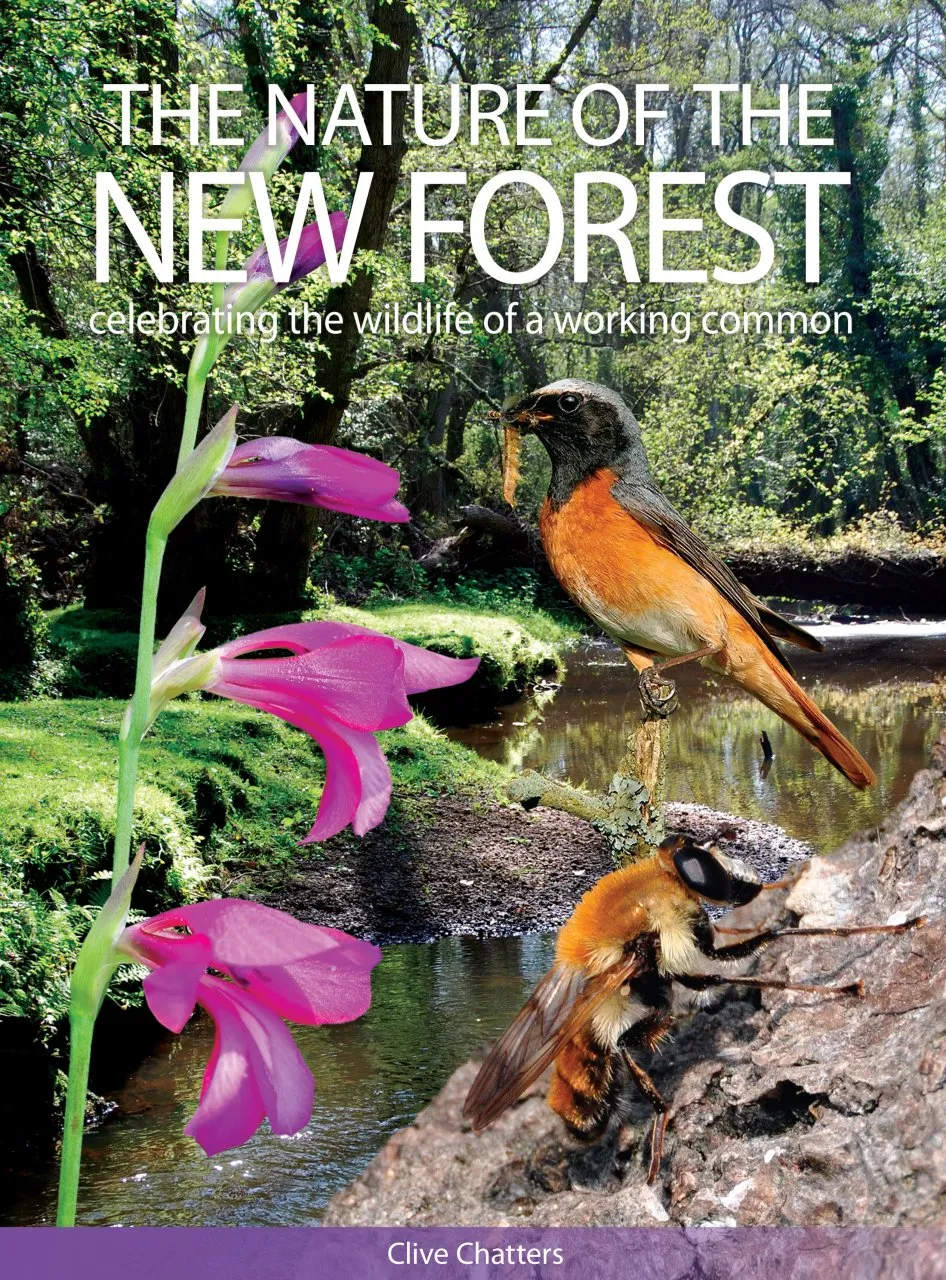

The approach follows other titles in the series by focusing closely on individual species, starting with plants and fungi (flowers & ferns; bryophytes; fungi; lichens) which are as well-recorded here as anywhere in Europe; and then a full 80 pages on insects and other invertebrates, also well studied and recorded, followed by chapters on fish, reptiles and amphibians, birds, and mammals. There are preliminary chapters on the physical forest and on the Forest’s many habitats. Final chapters weigh gains and losses (for there have been losses even here), and a review of the essential dynamism of the Open Forest. It is lavishly illustrated with hundreds of colour images of a high standard, a portrait gallery which gave me hours of pleasure on its own. I am not keen on the cover design, which mashes images of three charismatic species against a Forest backdrop, but I suppose it is a matter of taste. Those who know Clive Chatters’ other books will warm to this one, which is characteristically confident, very well researched, richly detailed, and thoroughly ecological (i.e. of species in their place). He has not felt the need to repeat the historical detail in Colin Tubbs’ book, The New Forest (1985), but as a review of the Forest’s wildlife in close-up it is unrivalled. As the subtitle proclaims, it is a celebration of the tremendous biodiversity that can survive on a common, so long as it is robustly defended. With a foot in both camps, conservationist and verderer, Clive Chatters is not only the Forest’s leading naturalist, but also its champion.