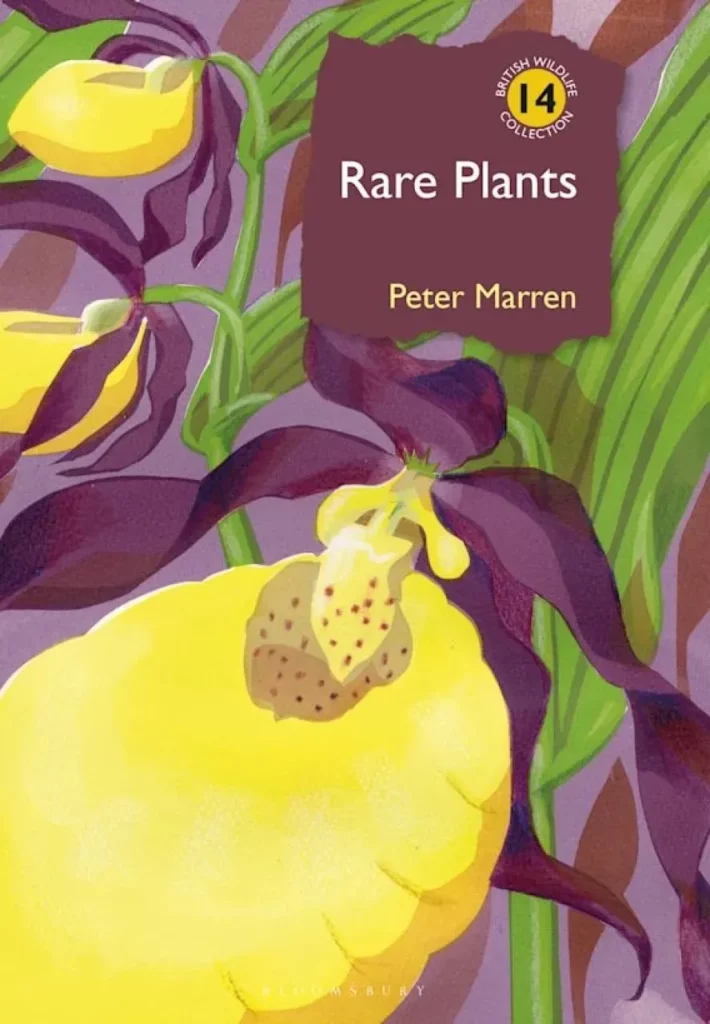

As a passing interest in wildflowers turned into something more, one of the books that nudged me over the edge and into obsession was the publication of Peter Marren’s Britain’s Rare Flowers in 1999. His engaging, conversant prose was far removed from the rather dry academic texts on similar subjects that served to inform, but lacked soul. This was a book rooted in decades of personal observation, the joy of discovery, and an appreciation of place. Twenty-five years later, it has been revisited, with Rare Plants published as the 14th volume in the constantly excellent British Wildlife Collection, complete with a stunning front cover by Carry Akroyd of one of our rarest orchids, the Lady’s-slipper.

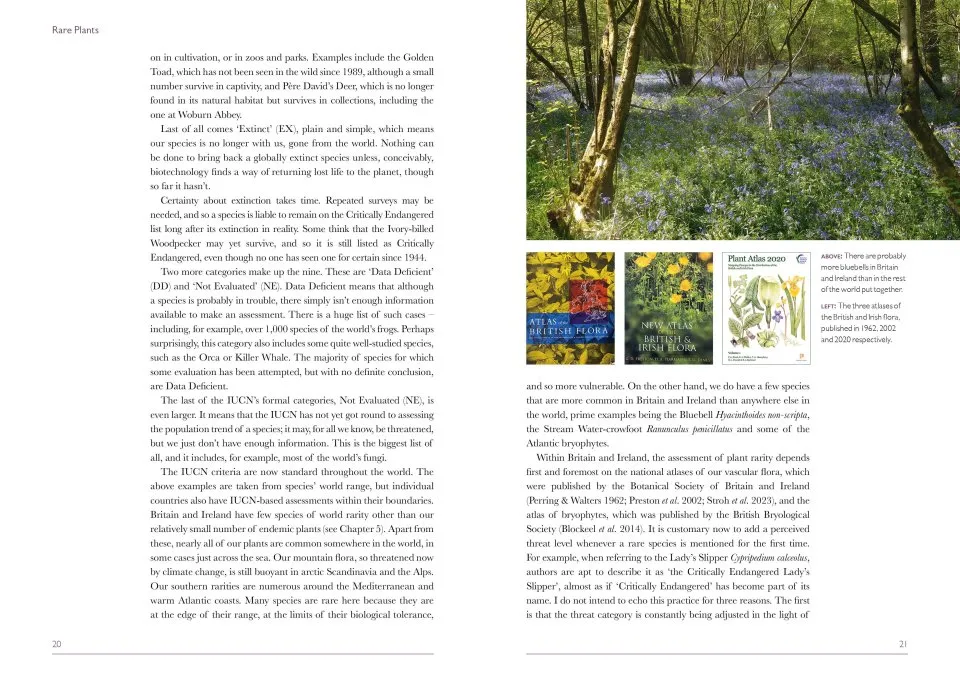

Marren has fashioned something that is substantially more than simply a revision. The geographic scope of the book is expanded so that it now covers Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands, or ‘the British Isles’ in old money. The text has been completely rewritten, and its scope significantly broadened. For example, there are now chapters detailing the delights of non-vascular plants (bryophytes, stoneworts, seaweeds and desmids), the challenging world of our apomictic flora (dandelions, hawkweeds, lady’smantles, whitebeams, brambles, sea-lavenders), and an examination of the crucial role that hybridisation plays.

View this book on the NHBS website

There are requisite chapters defining rarity, the various reasons for why a species is rare (it is not always our fault, but often is), a marvellous telling of how and where rare plants were discovered, and by whom, and the continued discovery of new natives, some only recently recognised as ‘true species’ following phylogenetic studies that led to an upgrade from lowly varietal or subspecies status. The relatively good news of this latter chapter is contrasted by the inevitable examination of species that we have lost, although some, like Cottonweed, persist in Ireland after vanishing from Britain by the 1930s, and others, such as Purple Spurge, might yet return.

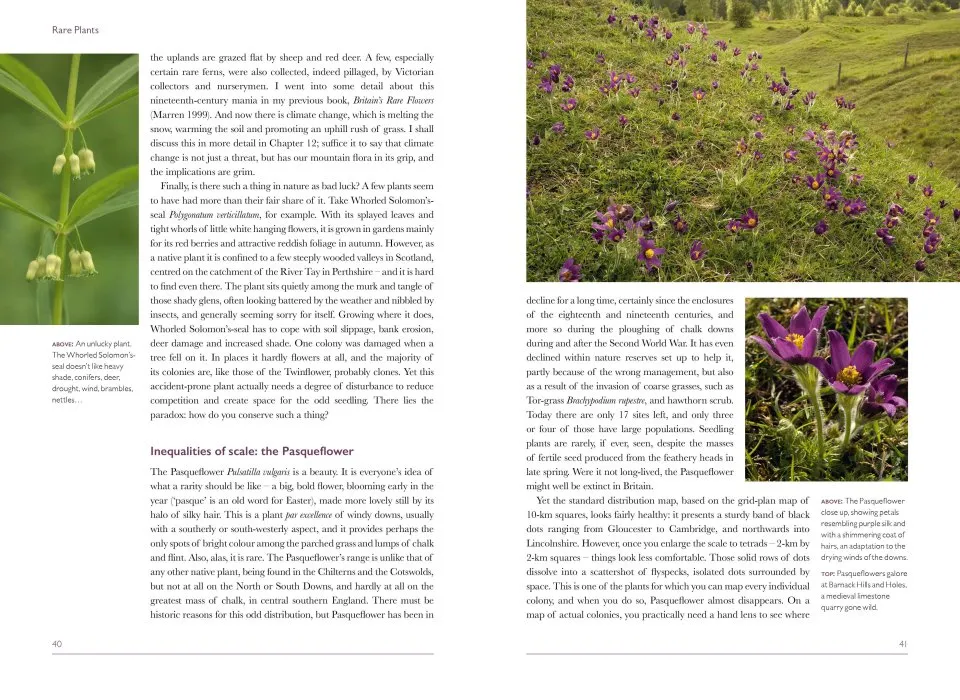

Inevitably, a book about our rare native flora must contain some doom and gloom, and examples are not hard to find. It seems probable that some of our rarest arctic-alpine plants will join the list of the ‘lost’, succumbing to the effects of a changing climate, as will other species in a variety of differing habitats due to a decline in the quality and/or quantity of the specific niche they require. But there are also tales of success and of hope, a detailed chapter about our endemic flora, small though it is in number when compared with other countries who were not under ice 10,000 years ago, and a thoroughly engaging account (‘Plants and people’) of how plants have inspired art, literature, cultural identity and a love of the natural world.

The liberal use of case studies adds clarity to the topic under discussion, and each was clearly selected with care. Marren’s extensive experience of searching for rarities in the field is often related in a perfect search image not available in your average field guide, my favourite being Ground Pine, which is described as ‘a fuzzy, grey-green object, often with a touch of ginger, about the size of a golf ball’. Spot on. And the wealth of illustrations and photographs, many of which were taken by the late, great Bob Gibbons, are constantly excellent. I challenge you to look at Small Cow-wheat on page 356 and not want to make plans to see it.

Marren’s writing helps to remind us, and I suggest that we do need reminding, that an appreciation of rare plants has nothing to do with designations, targets and spreadsheets, and everything to do with how we approach and interpret and value the landscape that we live within. His final chapter, distilling considered thoughts about the current state of nature conservation, should be made compulsory reading. On finishing this fresh and ultimately uplifting celebration of our rarest plants, a quote by Norman Moore from over 40 years ago came to mind: ‘It cannot be said too often that it is as much the conservationist’s job to keep common species common as it is to ensure the survival of rare species.’