The great success of Isabella Tree’s Wilding and the Knepp Wildland project which it described now leads to a book designed to promote and guide rewilding as an approach to nature conservation everywhere. The authors’ experience at Knepp remains prominent, but we also hear about rewilding projects elsewhere in Britain and abroad. Guidance is given not just for rewilding farmland, but also for the full range of semi-natural habitats, gardens and urban environments, all backed up by advice from a substantial cast of practitioners from all walks of conservation life, copious citations and lists of organisations that can help. In short, this is both a review of the idea and benefits of rewilding and a well-illustrated recipe book for its implementation that brings together the experience accumulated by the authors and a wide range of land managers and specialists.

At first glance The Book of Wilding is about a particular and still novel approach to nature conservation, but, as the first chapter makes clear, it covers the whole of nature conservation and the underlying concepts, but from a new and refreshing standpoint: it advocates hands-off, proactive site stewardship based on natural processes, especially where nature has been greatly diminished by industrial farming, plantation forestry, engineered rivers and urban development. Here we have conservation on the offensive where previously it was defensive and only partially successful. No wonder rewilding is attractive: conservation becomes creative and expansive, rather than just taking the hits.

View this book on the NHBS website

A conclave of Knepp advisers having failed to agree a definition of rewilding, this book wisely accepts that rewilding is a broad spectrum of measures applied according to circumstances. Full-fat rewilding (‘Pleistocene rewilding’) would involve reinstating a full set of megafauna in a vast Highland reserve, within which vegetation and watercourses etc would function naturally (without management) and species would interact according to their needs, capabilities and adaptability. The outcome is unpredictable, but it is likely to fluctuate and to be biodiverse. It would not be completely natural, given the all-pervasiveness of human activities, but it would be close.

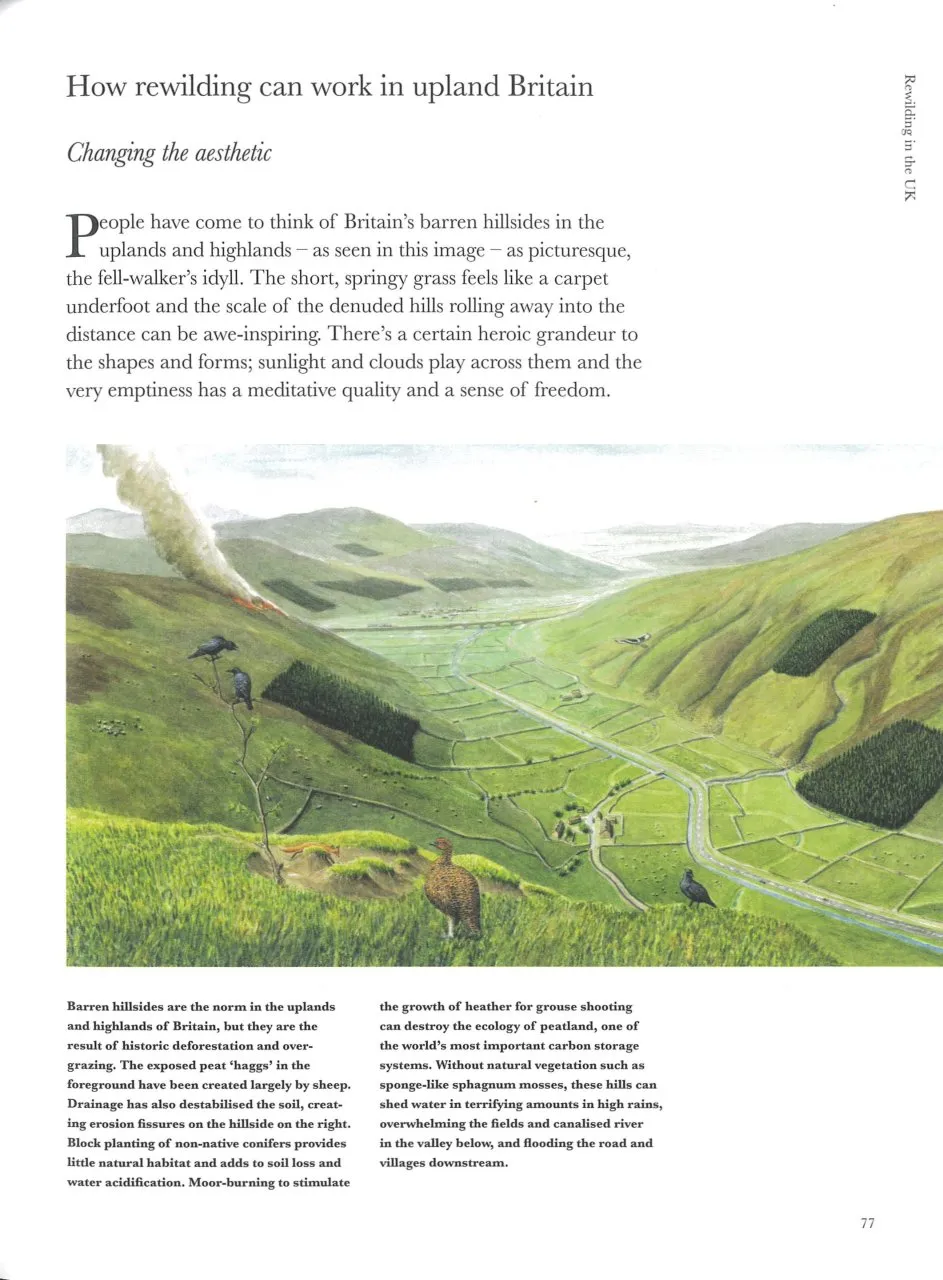

In practice, most rewilding involves permitting natural processes to be more prominent than they are under intensive farming, plantation forestry and the associated close control of rivers and land drainage. The commonest projects involve river restoration and the Knepp model of free-range pasturage with a variety of large herbivores, inspired by the work of Frans Vera and financed by meat sales, subsidies and recreational use. Traditional forms of land management that have long sustained high biodiversity and some natural patterns and processes, such as coppice-with-standards woodland management, are not included, though traditionally managed places like the New Forest have inspired rewilders.

Rewilding is not a damascene realisation that traditional conservationists got it wrong. Rather, it has grown out of research from the 1960s onwards on ecological isolation, metapopulations, habitat networks, disturbances in natural ecosystems, and the realisation that humans had impacted the megafauna long before the Neolithic. Traditional conservationists were well aware of this work and contributed to it, but ‘rewilding’ has crucially given this thinking an identity. The courageous early rewilding projects at Ennerdale and Knepp added practical implementation to an already saturated solution of ideas which quickly crystallised into a vigorous and creative approach to nature conservation. Interestingly, modern rewilders echo the Victorians who managed to safeguard Epping Forest, the New Forest and many other semi-wild places which we now take for granted, partly for public recreation and partly inspired by supposedly natural forests.

The book concludes with a fascinating quiz developed by Benedict Dempsey, a social scientist, that asks ‘How wild are you?’. Answers to ten questions lead to four kinds of nature conservation, namely ‘management of changing nature’, ‘protection of threatened nature’, ‘innovation in nature’ and ‘re-establishment of wild nature’. Most traditional conservationists will surely identify with all four, but in different circumstances, favouring rewilding here, restoration of former management there, and promoting more naturalness elsewhere. Those of us who ‘look back’ do so, not for antiquarian reasons, but to understand better the habitats and wildlife populations we have now. And if we restore traditional management, this is because it maintained rich habitats. In a sense all nature conservationists are rewilders and always have sought greater freedom for natural processes and populations than commercial land management would allow.

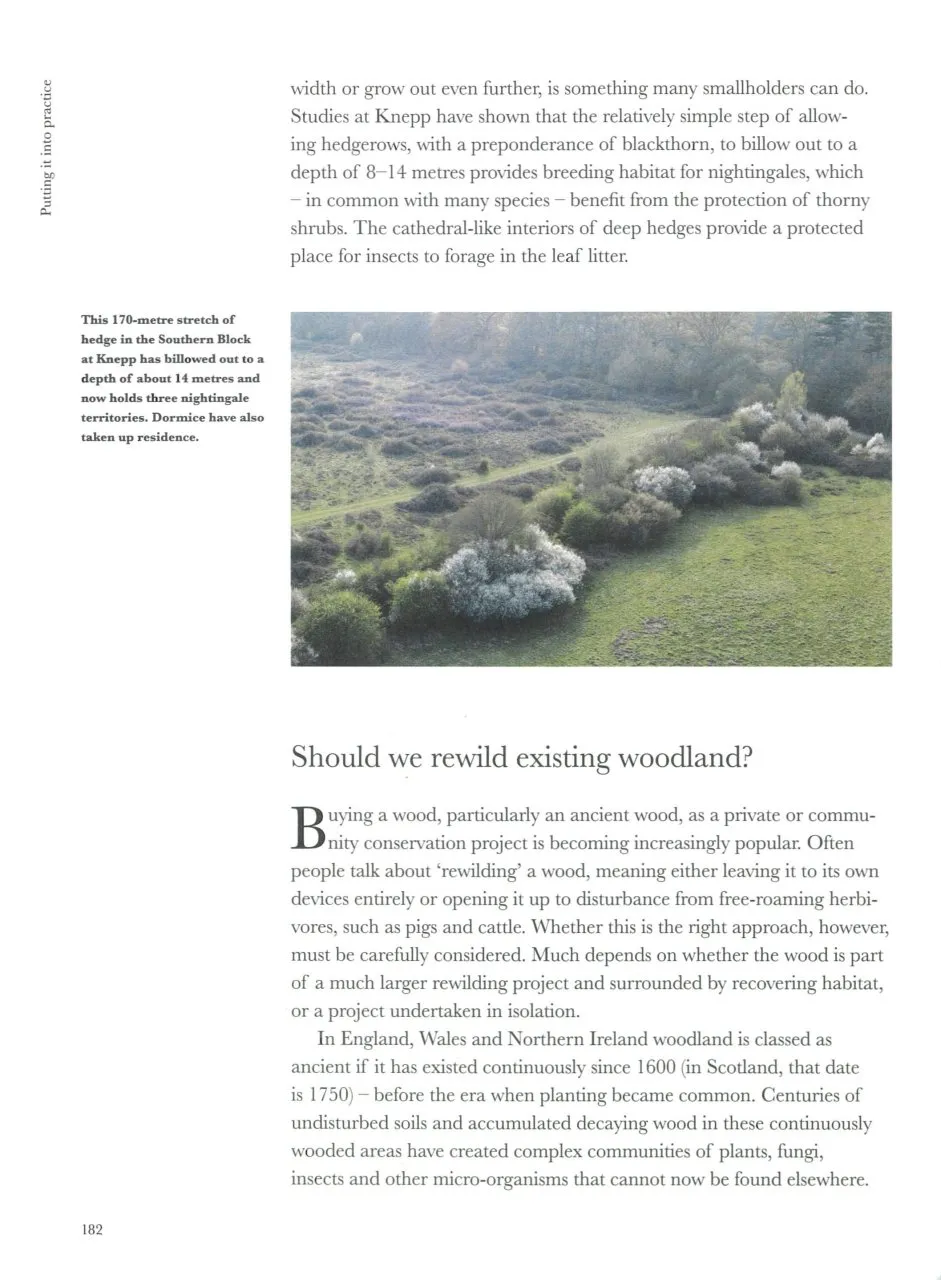

Rewilding generates many questions which the authors address. Can we feed ourselves if rewilding spreads? We can, and we do not have to become fully vegetarian. Will rewilding pay? It has at Knepp, but continuing subsidies remain important. Is rewilding for everyone? Almost, as one would expect from such a broad spectrum of possibilities, but the authors echo my particular caution over isolated ancient woods. Can we stand the uncertainty and open-endedness of outcomes inherent in rewilding? Most can, but one wonders whether auditors and official paymasters will be happy. Will the newly wild places be safe for visitors? Sensibly, the authors are investigating special legal provisions for designated rewilded ground. Does rewilding really make sense in cities? Perhaps the most encouraging chapter deals with urban rewilding, which reaches more people of all social backgrounds than rural rewilding and captures the intensely active, multicultural and innovative character of city life.

This will be an important inspiration and reference work for years to come. It will soon need updating, but for now it offers numerous leads into the background literature and a grippingly readable introduction to many aspects of ecology, wildlife, land management and the many ways in which individuals can improve our environment.