Twenty years ago, Peter Marren described the Woodland Trust as one of conservation’s ‘surprise successes’. It has grown from tiny acorns (perhaps quite literally in this instance?) planted in Devon by its founder, Kenneth Watkins, to one of the largest and most influential conservation charities in the UK today. It has 340,000 members, employs some 400 people, and owns some 25,000ha of woodland across the UK. It has grown in influence to challenge the Forestry Commission in its adopted role as advisor and advocate on all matters regarding trees, woods and forestry, and now plays quite a key role in advising government and public bodies. Its excellent work on veteran and ancient trees has been pioneering, forging the path for their recording and protection. It is the go-to charity for numerous celebrities, magazines and corporations. Not surprising, then, that it is looked on with envy by other environmental charities!

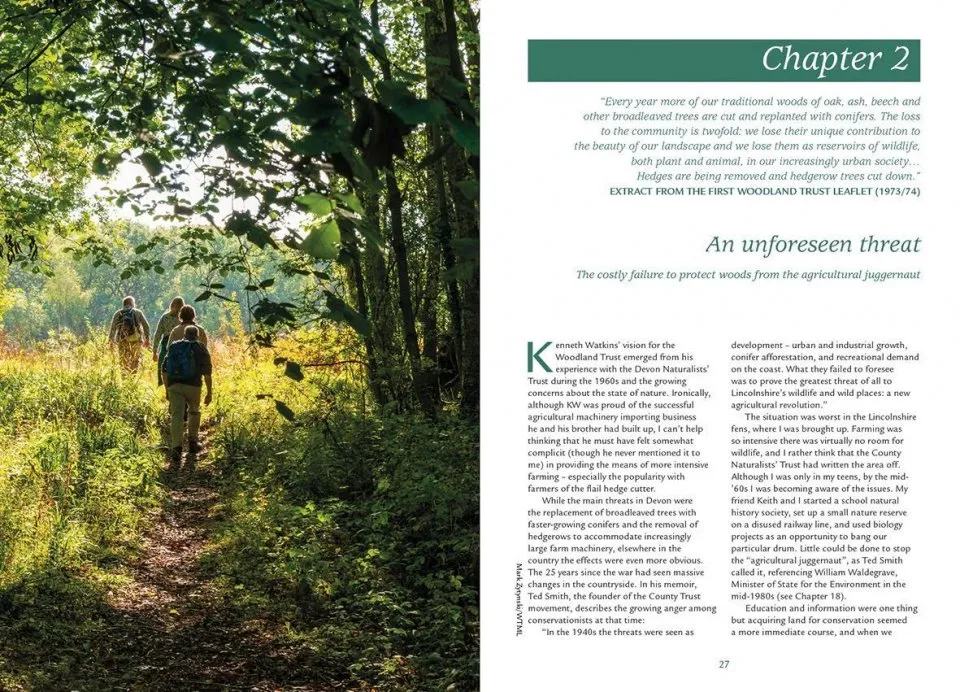

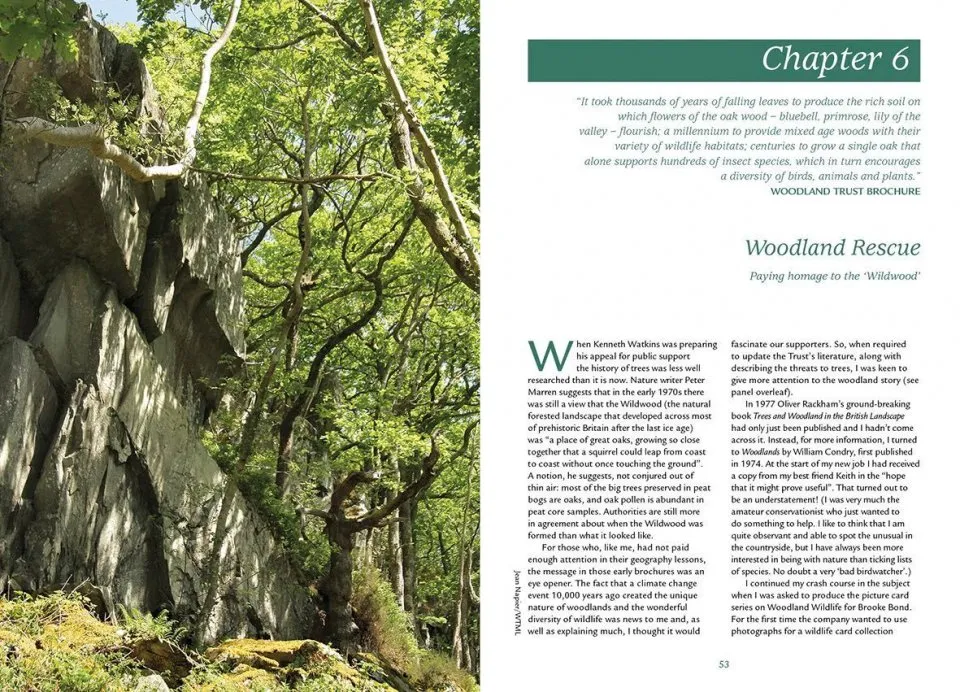

This book details the origins of the Woodland Trust over its five decades of existence, as experienced by its author, John James, its first full-time employee and Chief Executive. As such, it is a personal account as well as a history, with a quirky but very engaging style. It goes further though, setting the context within which, decade by decade, the Woodland Trust was operating as Britain emerged from post-war austerity into the ‘Locust Years’ of the 60s and 70s. It was the loss of trees, hedgerows and woods from the landscape that led to the Trust’s formation, that shaped its straightforward aims of creating or securing woods and, ultimately, its extraordinary success.

View this book on the NHBS website

Early chapters chart the origins of the Trust, its growing role in planting trees and establishing woods (it has planted over 50 million trees since its inception in 1972), its growing skills at handling appeals, membership and the use of modern technology and marketing methods, and its increasing involvement with community woods and people. The novel way in which a very large legacy specifically made for the provision of park benches was transformed into an art-based project is a lesson in creative thinking that many could benefit from.

Later chapters look at the Trust’s growing role in advocacy, campaigns and policy of expansion, moves not always comfortable with its trustees and staff.

Oddly, the book’s final chapters, essentially those covering the years after the author left the Trust, are treated merely as sketch summaries, as if they were of far lesser import and interest. A great shame, as the Woodland Trust has been hugely active since 1997. This very sudden shift in style and treatment is not explained.

The book provides a keen understanding of the Woodland Trust, its style, sometimes described as ‘aggressive’ in its marketing, and in particular its approach to woodland management. It has long suffered from the well-founded criticism that its ancient woods are not restored fast enough, and that its woods are not managed as well as they could be for wildlife and nature conservation, being far too shady, dark and cold, especially for many woodland butterflies. Where the book is strongest, reflecting the Trust’s greatest achievements, is in describing the enviable record of engaging with communities, people and places, and in establishing a huge raft of new woods as permanent features in the landscape. The Woodland Trust is very likely to be with us for at least another 50 years, and this book does a good job of setting out the records of its origins. Its prospects look good in a world that certainly needs far more nature.

From Little Acorns is well illustrated, and well written in an engaging and useful fashion. It suffers from a lack of an index, and from several of the photographs being unlabelled, and it stops short of being a full and engaging history with limited coverage after 1996. For those with an interest in the challenges of establishing a large environmental organisation, however, and those with an interest in the history of conservation as a movement, this book is well worth purchasing.