All birds are great, of course, but Hen Harriers are just that bit better! Whether you get to watch them ‘skydancing’ over the moors in spring or, like me, you wait for them to come into a winter roost, seeing a Hen Harrier is always an ‘expectation plus one’ experience. I have therefore been awaiting this book with interest.

Ian Carter and Dan Powell collaborated in 2019 to create The Red Kite’s Year, which was a great mix of Ian’s specialist knowledge and Dan’s minimalist but powerful illustrations. Now the same two individuals have combined to tell us about Hen Harriers. The texts of both author and illustrator are run in tandem but with different typefaces, allowing Ian’s facts to be supported by Dan’s field notes. Dan’s wife Rosie also contributes some extra illustrations.

View this book on the NHBS website

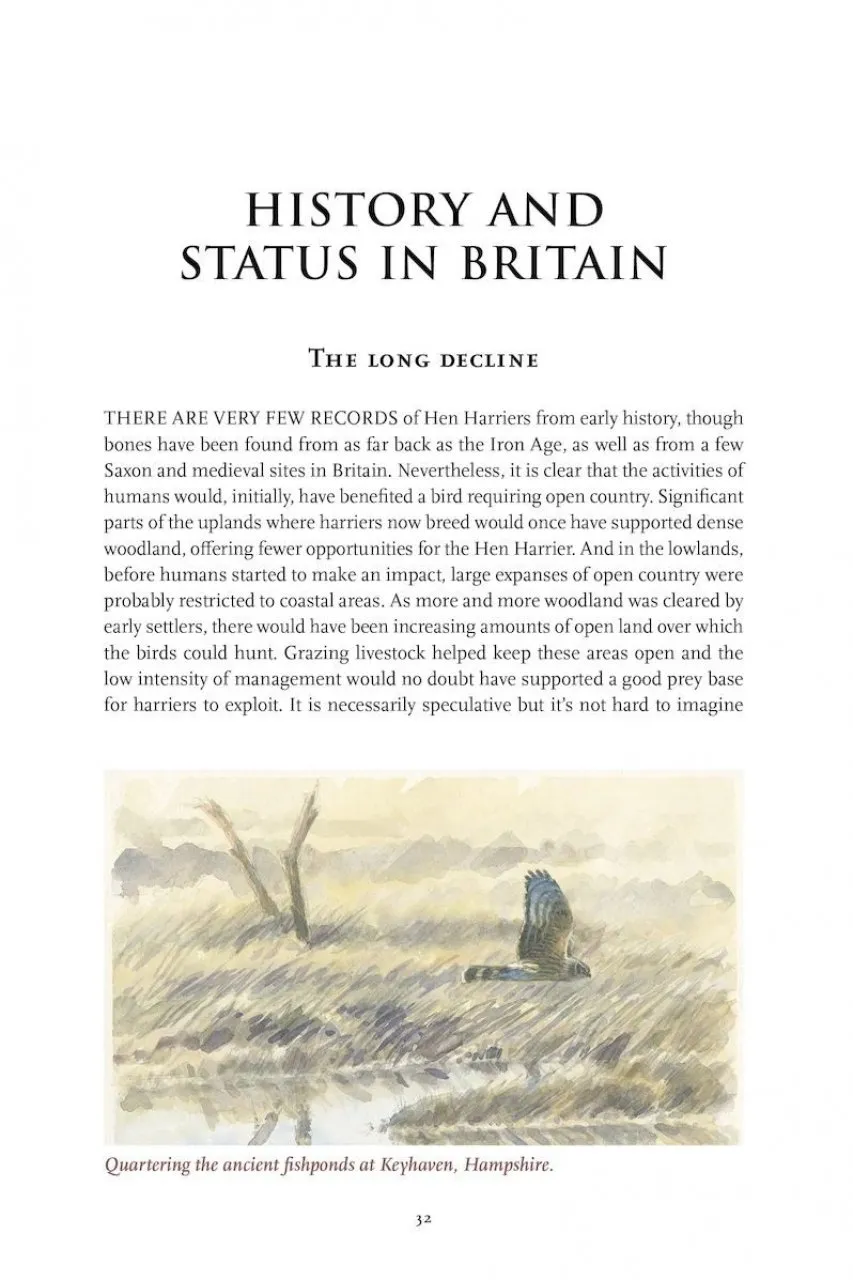

The book is created around one year in the harrier’s life, and, while we learn about what the birds will be doing in each month, additional facts are included within each chapter under clear headings. So, within January and February we learn about communal roosting and the typical hunting behaviour in winter haunts – the females pursuing rather larger prey than the slimmer male. We get to understand why roosts are important, and how the birds use them – not snuggled together, but spaced out. In between the months there are other chapters charting the long decline in this species’ numbers, mainly in areas that are used for grouse-shooting.

Chapters on the breeding season are spread from March to June, with much information about diet and the challenges of hunting, along with the famous food passes that are typical of all harrier species. For those who watch breeding Hen Harriers, these passes in June are valued on a par with seeing the male ‘skydancing’ to advertise his territory in April.

The joy of all these wonderful things is brought into sharp contrast by the severe challenges that Hen Harriers face in the uplands, against those who take delight in seeing a Hen Harrier only when it is dead. Ian Carter describes the problem of persecution and assesses some of the possible solutions, including diversionary feeding, brood management and plans to release young Hen Harriers in the lowlands of England. He also reminds us of the other major debate in the uplands: the matter of heather-burning, which is subject to debate on both sides over whether or not it is good for wildlife.

Having dealt with some very depressing issues, the text then moves to the late summer and we learn about the chicks’ development and early flying experiences, and also the threats from other birds of prey at this time. Before long the chapters take us towards autumn, and winter arrives fast. Some Hen Harriers will have moved to Spain for the winter while others will stay closer to home. Indeed, the justification for moving quite so far is diminishing as warmer winters and earlier springs become the norm in Britain. We are reminded that this is a bird that faces many threats, including from natural causes, but the greatest threat is still from human activities, and the signs are clear. If we want to see more Hen Harriers in Britain it is down to us to make that happen. Some might argue that with 24 successful nests in England in 2021 (compared with just four in 2016) the situation for Hen Harriers has been reversed, but whether this growth can be continued lies with the government and how it balances the wishes of moorland-owners with those who worship the harriers. What is certainly true, however, is that the case for this species to be the iconic bird of the uplands has been successfully made.

The Carter and Powell duo have triumphed again. This book is informative and relevant, and a delight both to read and simply to look at. What will be next? Maybe the Golden Eagle’s Year, or the Peregrine’s Year? I, for one, hope that there are more books to come from this team.