British Craneflies is the third in a series of books published by BENHS covering British flies, and a long-awaited one. The test keys have been in circulation for several decades and have much increased the popularity and recording of these insects during the long production phase. Craneflies are a fantastic group of insects for any naturalist wishing to gain a deeper understanding of habitats: ‘a significant element in description of ecological communities’, according to the author, and one that complements a vegetation-led approach. Many of the scarcer species have specialised requirements. These might relate to ancient hollow trees of pasture woodland, freshwater cliff seepages on specific geology, or the finest spring-fed wetlands. Cranefly ‘assemblages’, i.e. the collections of species present at a site, can also form a good basis on which to evaluate sites for nature conservation.

The book provides introductory chapters explaining what a cranefly is, why you should study them, their biology, behaviour, body structure, key habitats, and how to observe, collect and record them. It covers more than 350 species, including all the true craneflies (families Cylindrotomidae, Limoniidae, Pediciidae and Tipulidae) plus the more distantly related fold-winged craneflies (Ptychopteridae) and winter gnats (Trichoceridae). This is a sensible approach that makes the book a lot easier to use for any less experienced naturalist taking the leap into the unknown and unclear of where the boundaries might lie.

View this book on the NHBS website

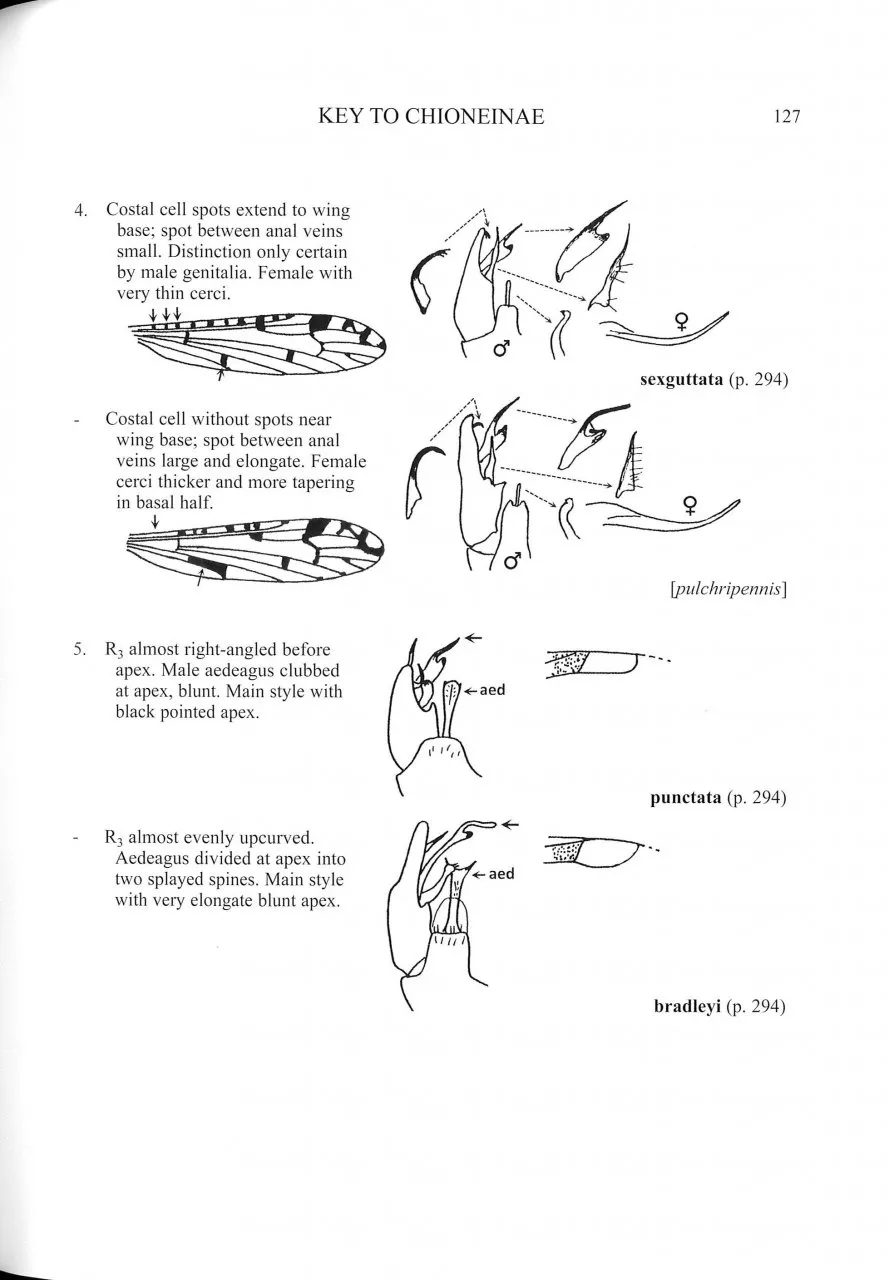

The main ‘meat’ of the book, as with the others in the series, is the identification keys and species accounts. As noted above, the test keys (which are standard dichotomous keys) were trialled for several decades and are probably as user-friendly as is possible without losing the rigour required to bring about accurate species-level identification. You will need specimens and a stereo microscope to see some of the features, but the book also emphasises how much can be achieved in the field with just a 20× hand lens. The keys are very clearly presented and illustrated – a master class in key construction. I particularly like the way in which the keys and species accounts work in tandem, the accounts expanding upon what is in the keys with reassuring summaries of what makes something distinct and how to avoid confusion with similar species. Keys can become very unwieldy if you over-complicate couplets with too much of this information. I also like the way in which the large genera Tipula and Dicranomyia are broken down, using several bite-size keys rather than a single long one. These simple decisions can radically improve the user-friendliness of a key. It also reveals the extent to which the author understands the mindset of an amateur naturalist and cares for the novice as much as for the expert. Not all identifications will be easy. You will still have some wrestling matches with legless or damaged specimens, and at times you may need to refer a specimen to an expert for verification or compare it with another reliably identified voucher specimen in order to be certain of what you have. That is no different, however, from the challenge you encounter in identifying many other wildlife groups, and in no way does it represent a shortfall of the book.

The species accounts generally cover two aspects. First, a general description of a species is given, with an emphasis on what makes it distinctive and the pitfalls to be aware of. As noted above, this information is designed to be used alongside the keys. It is invaluable for novices but is also a useful aide-memoir for more experienced recorders. The second part of the accounts concentrates on distribution, habitat preferences, biology, flight period, and how best to find the species concerned. These, again, are a master class of writing – highly authoritative, yet engaging and not overly technical or wordy. Throughout the book, the author’s deep understanding of geology, habitat, ecology and nature conservation creates a vocabulary, pitch and cadence to the text that make it wonderfully engaging, giving it a sort of ‘New Naturalist’ flavour. Every species is provided with a vernacular name.

The final sections of the book are dominated by a checklist of British species, an extensive bibliography, diagrams of male genitalia, wing plates, and a selection of photos of live craneflies. The identification of many superficially similar species can be confirmed by reference to their male ‘bits’, even when the rest of the specimen is badly damaged. With practice, you will soon learn to identify many craneflies quickly and reliably by knowing which key feature or combination of features to look for. You may even acquire a photographic memory of male genitalia and wing venation!

I would strongly recommend this book (and the others in the series) to anybody wishing to broaden his or her natural-history interests and keen to gain new and exciting perspectives on the sites, habitats and landscapes which they visit. Like all such books, it is one you will need to grow into, but in time it may become a treasured item on your bookshelf.