Seasoned myrmecologists will probably want this review to answer one fundamental query: ‘I’ve got “Donisthorpe”, do I really need another book on ants?’ The answer is, in my opinion, a resounding ‘Yes!’ Horace Donisthorpe’s classic work British Ants was published nearly 100 years ago and for many decades was the definitive work on the biology, identification and behaviour of this group, focused, of course, on British species. In this new tome you will not find technical diagrams of internal organs nor excessively detailed identification tables (although a relatively simple identification key is appended towards the end of the book). What it does contain is a wealth of information about the evolution, biology, sociology and ecology of the global ant fauna, though still with a bias towards British species. This is all served up in a very readable, popular and amusing style. On discussing energetics and activity levels, Richard summarises the situation: ‘They only forage when absolutely necessary. A bit like teenagers.’ One cannot imagine Horace talking in such terms, although it is possible that the average teenager of his time was a distinctly different beast from that which has evolved today.

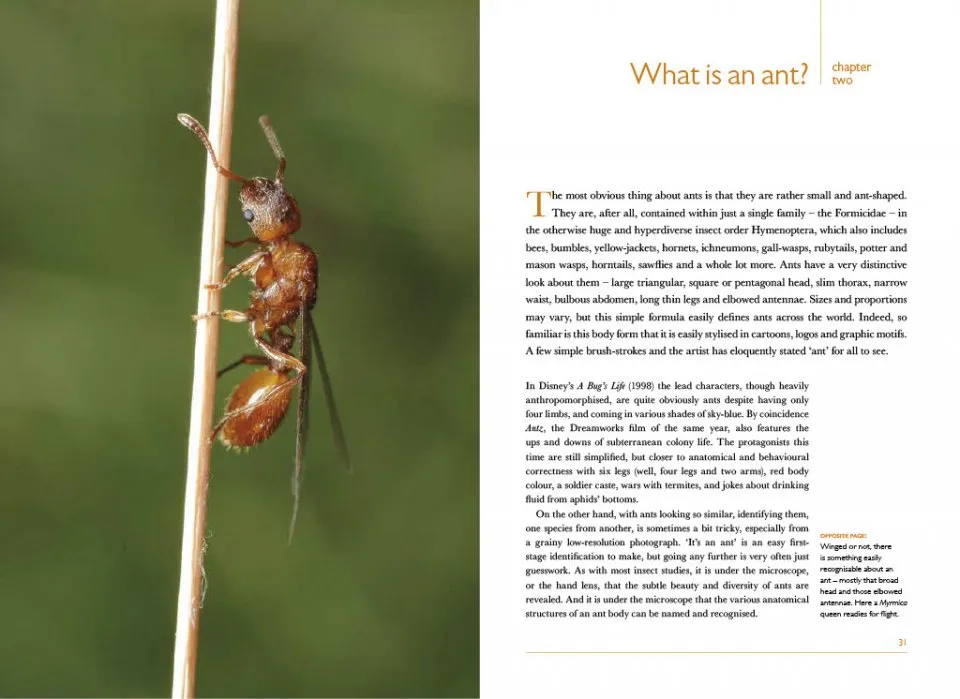

The book is richly illustrated with colour photographs and packed full of fascinating facts, such that, while the beginner might be surprised to discover that there are upwards of 50 native British species, seasoned naturalists can still be surprised by the fact that just over The Channel, in France, this number leaps to over 200 species. The numbers of individual ants claimed for tropical super-colonies are mind-boggling, and there are plenty of examples of how such masses of ants can have an impact on the local ecology and even landscape. There is, as one might expect, a lesson in ant anatomy, but this is served up in a very digestible manner and with interesting examples concerning the extremes of mandible and head size and how these fit in with one’s role in ant society.

View this book on the NHBS website

Chapter 3 is devoted to a discussion of British ants, providing outlines to their identification, ecology and distribution without pretending to be a full descriptive catalogue, as the author himself admits. It is detailed enough to consider recently arrived ‘tramp’ species, such as the Argentine Ant Linepithema humile, Hypoponera ergatandria and Pheidole megacephala. It also considers what the author describes as ‘nearly-British’ species, e.g. Aphaenogaster subterranea and Messor capitatus, which are widespread on the near Continent or regularly found in commercial traffic and so might feasibly arrive on our shores in the coming years. The book attempts to be bang up to date with modern taxonomy, which can be a hazardous goal when the taxonomists of the world still cannot agree. Thus, while Myrmica lonae is given its own entry, it is acknowledged that this may not be warranted and that the ant might suffer being synonymised with M. sabuleti, from which it was split. There is a similar treatment of Lasius myops and the very intricate calculations needed to apparently separate it from the very similar L. flavus. Overall, these accounts provide a very useful, bite-sized account of each species for those not familiar with our fauna.

The chapter on the evolution of ants includes ever-fascinating photographs of ancient insects preserved in amber and discusses the inevitable paucity in the fossil record. This section also includes consideration of how ants fit within the overall order Hymenoptera, evolving from ‘ant-like wasps to wasp-like ants’ over the millennia.

A detailed discussion of the behaviour of species is dealt with in a typically down-to-earth chapter entitled ‘Being an everyday ant’. Topics here include foraging tactics, orientation in one’s environment, the manner in which prey is subdued, and the interesting analogies with human farming in the way in which some ants tend aphids or grow crops of mould on harvested leaf matter. Another human trait, the ability to wage war on one’s own kind, also receives appropriate attention, as does the awkward topic of ‘slave-making’. The ability to punch above one’s weight by forming colonies, sometimes of colossal proportions, leads on from this, discussing the role of ants as predators, as prey, and also as landlords for the numerous other invertebrates that make their home within ant nests.

The ways in which ants have interacted with humans receives a chapter of its own, from biblical reference, through Aesop’s Fables to numerous starring roles in Hollywood films since the 1930s. The history of ant study as a scientific pursuit discusses the early works of John Ray and William Gould, through the 19th century to the aforementioned Mr Donisthorpe and beyond. The subsection on ants in history, literature and art is particularly interesting, with depictions dating back to the 13th century.

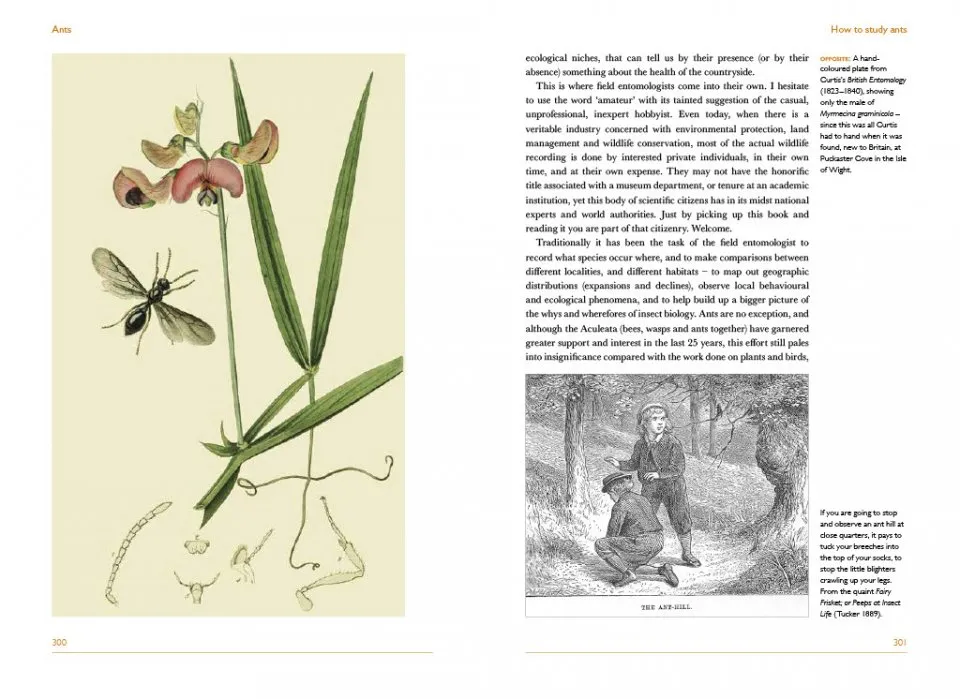

The book concludes with a chapter encouraging the reader to begin his or her own ant studies, giving guidance on how to look for, collect and thereafter study one’s captures to whatever level suits. The experience of many years’ study is encapsulated here, including such sage advice as ‘it pays to tuck your breeches into the top of your socks, to stop the little blighters crawling up your legs’. Advice in rearing one’s own ant colony usefully includes a recipe for serving up ant food in captivity. To aid the novice, an earlier section of the book considers ant mimics and those other insects that might lead them astray in their studies. By the author’s own admission, the identification key is simple and covers only workers, but it is not aimed at the expert. Attention is drawn to the numerous technical papers and books dealing with the matter of identification as a priority. Its aim here is to encourage the reader to ‘have a go’ and see where it leads.

There is something here to suit all exponents of natural history, from the curious beginner to the seasoned entomologist. The author easily captures the attention of the most casual ant-watcher with occasional references to Disney animations, unfeasible ant action in the Indiana Jones franchise and the 1960s Hanna-Barbera cartoon ‘Atom Ant’, but in a way that does not detract from the serious scientific study that underpins this impressive work. Any magnum opus reference book that makes you laugh out loud at regular intervals cannot be all bad! As an aside, I have always thought that Tapinoma erraticum, the so-called Erratic Ant, would make an interesting modern reworking in animation…