Dandelions are funny things. To most of us there is only one kind, the dandelion, and indeed it was this composite, ‘Taraxacum agg.’, that was mapped in the New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora. But busy specialists have identified no fewer than 239 different and distinct British dandelions, about 150 of them native, even endemic, while the others have probably blown in from the Continent or were brought in with animal feed or wildflower seed from continental sources. Virtually all dandelions are apomicts, species which reproduce asexually so that each seedling is an exact copy of its single parent. What they all have in common is a deep tap-root, jagged leaves (dent de lion – lion’s tooth), hollow stems, and a yellow sunshine flower that later turns into a ‘clock’ of featherlight seed. But within that generalised form, miniscule differences can be discovered in the flower petioles, the double row of bracts beneath each flower, the way in which the leaves are lobed or marked, markings on the underside of the flower, and even the colour of the stigma. Such minute observation enables nearly every dandelion to be identified to a named species. That is so long as the material is fresh, and not collected out of season, and so long as you can master the vocabulary and use the keys. Picking by severing the leaf rosette just above the tap-root does no harm to the plant. As gardeners know, dandelions bounce back so long as the root remains undisturbed.

View this book on the NHBS website

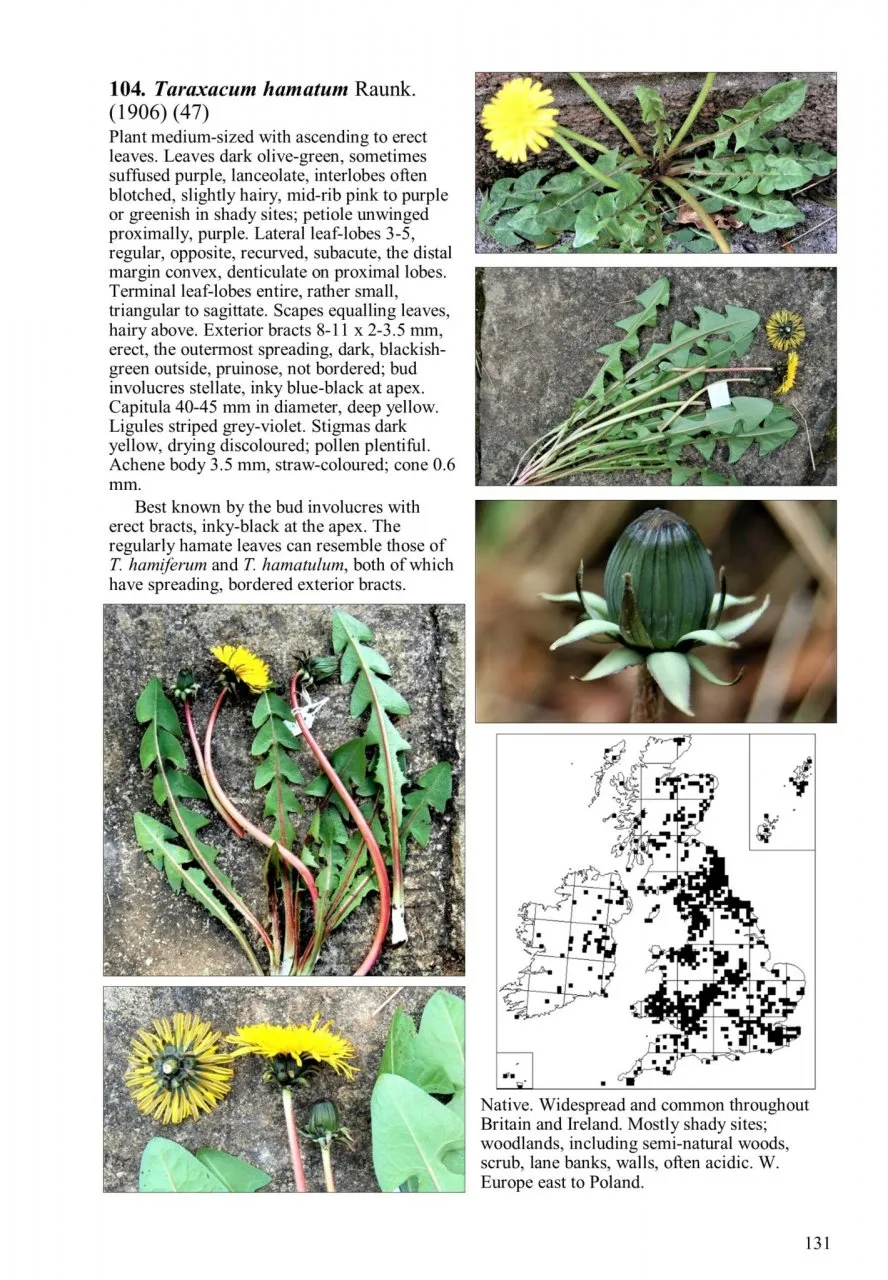

This new BSBI handbook is quite something. The modern miracle of colour printing allows every dandelion species to be reproduced in colour, and with up to five images per page, and at an affordable price. There are 1,000+ images in total. Each species is examined from various angles as well as in situ in the field. The previous BSBI dandelion handbook, published 25 years ago, had to make do with silhouettes, and was really a guide to dry material in the herbarium. This, in contrast, is a field guide, a guide to living plants. Each species is mapped at 10km-square level. Each is minutely described in botanical language, with notes on key identification points and similar species.

Like other BSBI handbooks, but even more so this time, it is aimed squarely at advanced field botanists and plant-recorders who may want to take on this challenging but clearly ‘doable’ group of plants. With the publication of this all-colour guide many undoubtedly will. And the best place to find a good diversity of dandelions? Road verges and urban wasteland, or the banks of an old sunken lane (though they occur in nearly every natural habitat, too). You are never far away from a dandelion.