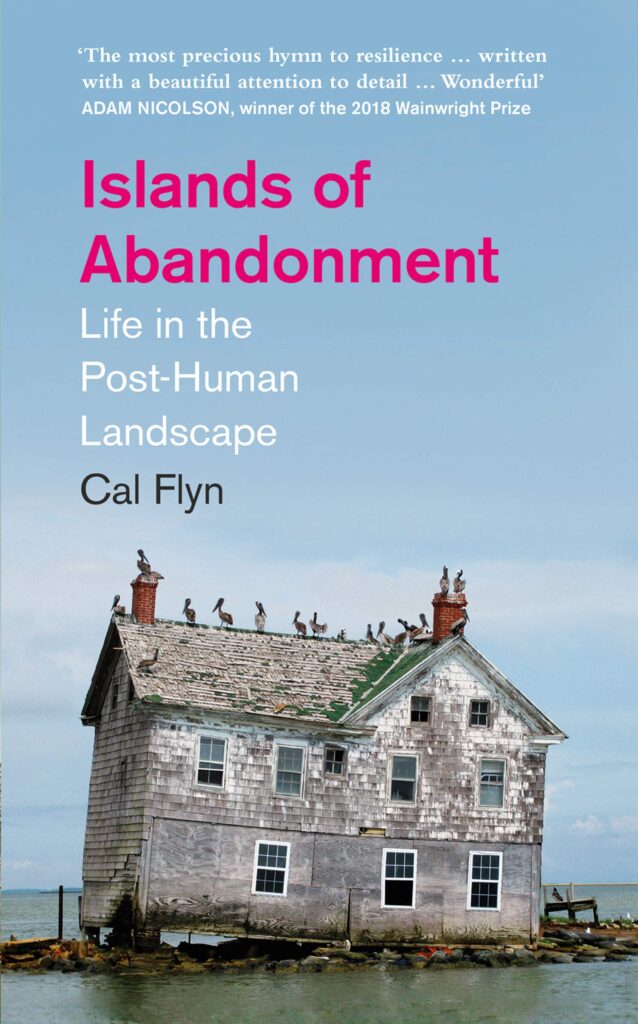

Nature reserves and National Parks strive to be the best examples of their kind: the wildest and best-preserved, the places with the greatest biodiversity. But unspoiled places are disappearing from the earth. The process of ecological decay is advanced and probably unstoppable. Instead, Cal Flyn, a young Scottish author and journalist, has explored their opposite: man-made wastelands, places made uninhabitable and from which the people have moved out. These are her ‘islands of abandonment’, our junk-piles and warzones and polluted, post-industrial hellholes. You could call them the new wild: deserted land in which new ecosystems might evolve and stabilise. Time is a healer, but it begs the question: how long does it take? And that raises another question: how much time have we got?

In some circumstances, environmental recovery may happen quickly. Canvey Wick near Canvey Island, designed as an oil terminal, is now insect heaven, and attractive, too, with its mixture of native and alien flowers, like a wild garden. The former open fields of Chernobyl have turned into developing forest harbouring wolves, elk, wild horses and even bison. As Flyn points out, as many acres of Soviet farmland were abandoned after the fall of communism as were lost to deforestation in the Amazon over the same period.

She visits a dozen of these ‘islands’ across the world, starting close to home with the shale bings in West Lothian, known as the Five Sisters, and proceeding through abandoned fields in Estonia, urban wilderness in Detroit and New Jersey, the cratered battlefield around Verdun where it is still unsafe to tread, the island of Montserrat half-buried by a volcano, and the ‘alien invasion’ of Amani in Tanzania, a once-rich natural ecosystem trashed by introduced bamboo and sugar-cane.

She spends a few lonely nights on the island of Swona, off the north coast of Scotland, abandoned by its last human residents in 1974, but their herd of cattle left behind. Half a century on, the descendants of those livestock are turning wild, prompting thoughts on what it means to be domesticated and what it means to be wild, and whether true wildness can return or be bred back. ‘They moved as one animal, comfortable in each other’s company… They don’t see me. It doesn’t occur to them to look.’ The book is full of deft and telling touches like this.

Islands of Abandonment is thoughtfully and sensitively written, at turns haunting and hopeful, and prompts us to rethink what we mean by wild and natural. Perhaps such places have the potential to become the functioning ecosystems of the future. Whether we ourselves survive that long is another matter. Climate change is making pessimists of us. As Flyn concludes, quoting the Book of Revelation, ‘the enemy may already be inside the walls. But we must find faith enough to fight. For in one hour is thy judgement come’.