In my experience, naturalists tend not to think about fish very much. This is a pity, because, apart from being beautiful (most of them, anyway), many have extraordinary lifestyles and form a key element of our wetland ecosystems. In this book, Mark Everard is on a mission to open our eyes to the fascinating world of fishes and to think of them as wildlife just as much as we do the dragonflies, Flowering Rushes, Water Voles and Kingfishers that share their environment. This is quite a challenge, because without donning a wetsuit it is hard to appreciate fully the colours, patterns and shapes of fishes in the wild. Nonetheless, bankside observation can produce rewarding results, as explained in a chapter on ‘fish twitching’, though there is no advice on what to do if you are desperate to see an Arctic Charr in the deeps of our glacial lakes.

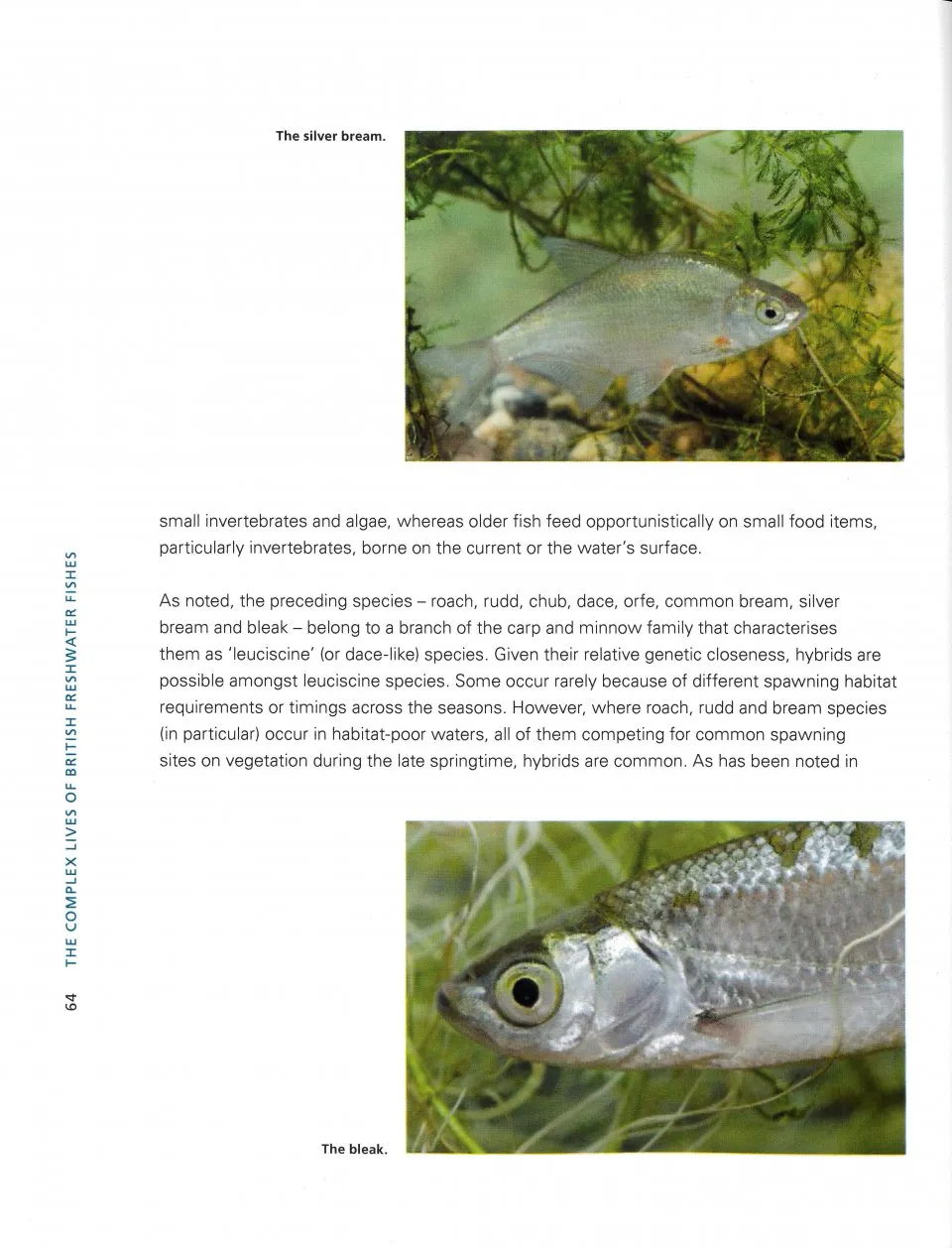

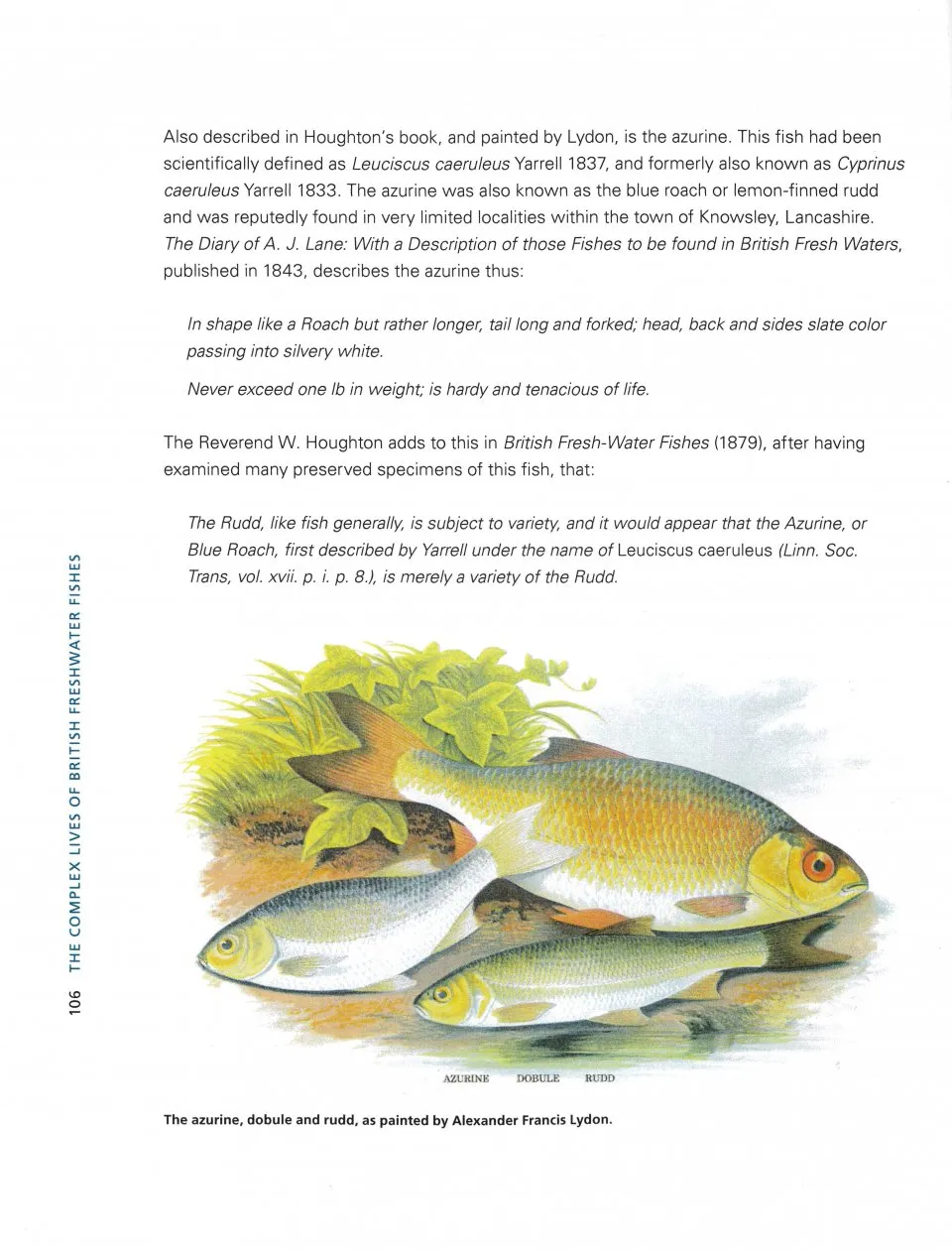

There are 52 species of freshwater fish with established populations in Britain, including seven marine species that venture into the lower reaches of rivers and 12 non-natives. The splendid underwater photography by Jack Perks shows many of these in their true proportions, rather than laid out on a slab or clutched in human hands – my personal favourites were the portraits of Roach, Perch, Pike and Grayling. The remarkable diversity of appearance, behaviour, movements and ecology of our freshwater fishes is well captured in a chapter entitled ‘The piscatorial dramatis personae’. The history of fish taxonomy is full of spurious species; several of these get an entertaining mention at the end of this chapter. Additional information about most of the real species is widely scattered through the book, with frequent excursions into cultural and historical aspects.

View this book on the NHBS website

The European Eel is simultaneously familiar and mysterious, with complex saltwater and freshwater phases in its unique life cycle, earning it the distinction of a chapter all to itself. It would have been interesting to balance this with a chapter dedicated to that other threatened long-distance migrant with an extraordinary life cycle, the Atlantic Salmon.

As an accomplished angler and aquatic biologist, Mark Everard has a wide perspective on the lives of fishes. I enjoyed his account of the varied spawning activities and development of young fish. There are well-informed discussions of conservation issues and the management of freshwaters for fish. He does not shy away from some of the more unfortunate impacts that fishing interests have inflicted on our freshwater ecosystems (I write that as a lifelong angler myself). Human-assisted movements of fish have profoundly altered the natural distributions of many native species, with undoubted, and largely under-studied, consequences for freshwater ecosystems. The Barbel, for instance, is a popular sport fish that now thrives in several rivers, including the Wye and Severn, which were never colonised by the fish after the last glaciation. The obsession of so many modern anglers with a long-established non-native fish, the Common Carp, has resulted in heavily stocked stillwaters often becoming turbid and ecologically impoverished. This has also intensified the pressure on our beleaguered native Crucian Carp through hybridisation and competition. Mark’s description of Common Carp as ‘pigs with fins’ is apt. Angling can, however, be a force for environmental good through combating pollution and engaging with habitat-restoration projects, of which there are increasing numbers on our rivers.

The book tells us little about the fishes of mainland Europe. A chapter summarising the main differences between fish assemblages in Britain and the Continent would have been more informative than one presenting curious facts about fish (Chapter 9). A few case studies of British rivers would have been a further welcome addition. Predation of and by fish is well covered, but I should like to have read more about competition between different species of fish. Minor quibbles include the frequent repetition of topics and a lack of diagrams to illustrate concepts mentioned in the text.

Overall, the 14 chapters offer a smorgasbord of information. There are six useful appendices, including a glossary and distribution maps. Everyone, no matter how experienced in matters concerning fish, will learn something from this book. If you want to extend your knowledge of our freshwater fishes, this is a good place to start.