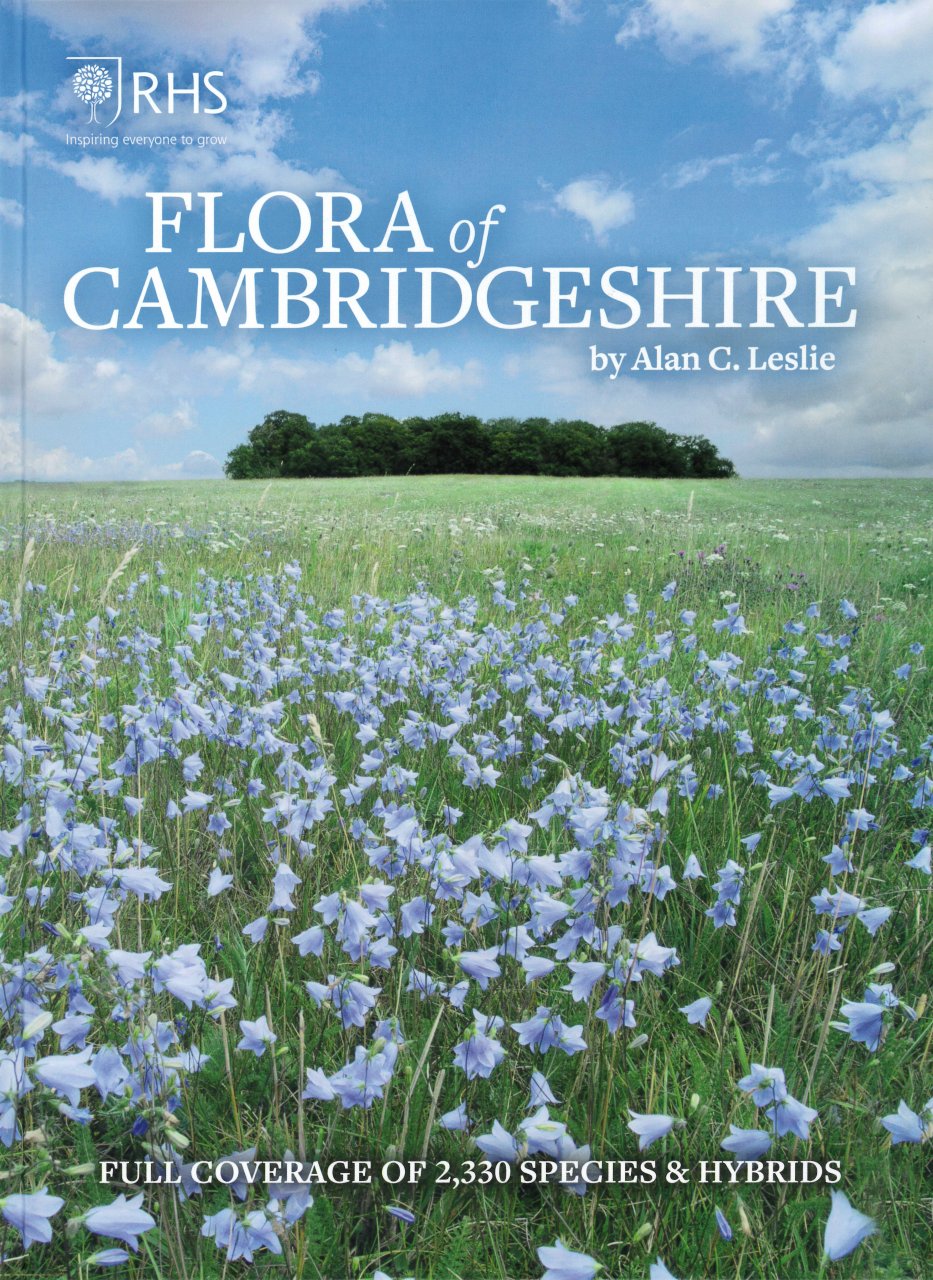

Cambridgeshire has the longest and most detailed record of wild plants of any county in Britain, and quite possibly in the world (by Cambridgeshire, botanists mean the old pre-1974 county, before it was amalgamated with Huntingdonshire and the Soke of Peterborough). Its first flora, the famous Catalogus Plantarum Circa Cantabrigiam by John Ray, was printed in 1660, and there have been many others since then, notably the magisterial Flora of Cambridgeshire by Charles Cardale Babington in 1860, and the surprisingly modest-sized flora of the same title by Perring, Sell, Walters and Whitehouse in 1964. The county has for long been a powerhouse of field botany, rooted in the Cambridge Botany School, now the University’s Department of Plant Sciences, and its 250-year-old botanic garden.

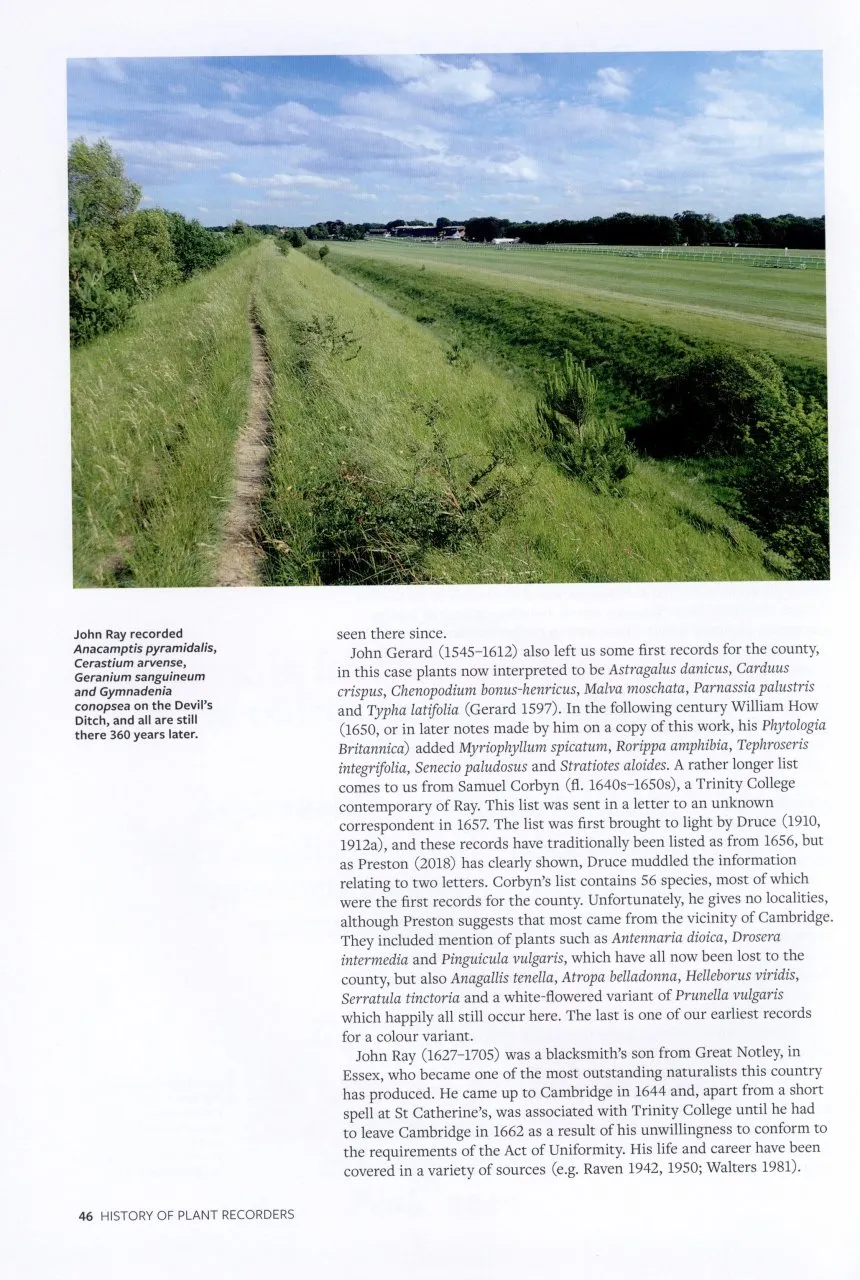

At the same time, few counties are as thoroughly transformed as Cambridgeshire. The remaining hotspots for native plants are tiny islands in an ocean of farmland or built-up land. As many as 120 species of native vascular plant have been lost since Babington’s day. Wicken and Chippenham Fens are the sole remaining relics of the old Fens. The once extensive chalk grassland is confined to chalk pits, or the Devil’s Dyke, the one place too steep to be worth ploughing. When I lived in the county, half a century ago, there were a lot of ponds around the village. They, too, have mostly gone. And yet this new Flora of Cambridgeshire dwarfs its predecessors. Field botanists have become increasingly specialised, and are as likely to look for plants on walls and churchyards as in nature reserves. Hybrids, micro-species and garden escapes are now routinely given the same treatment as native plants, and variation within a species is also minutely documented. Hence, Alan Leslie’s new Flora details 2,330 plant ‘taxa’, twice as many as the 1964 Perring one – and in a great deal more detail.

View this book on the NHBS website

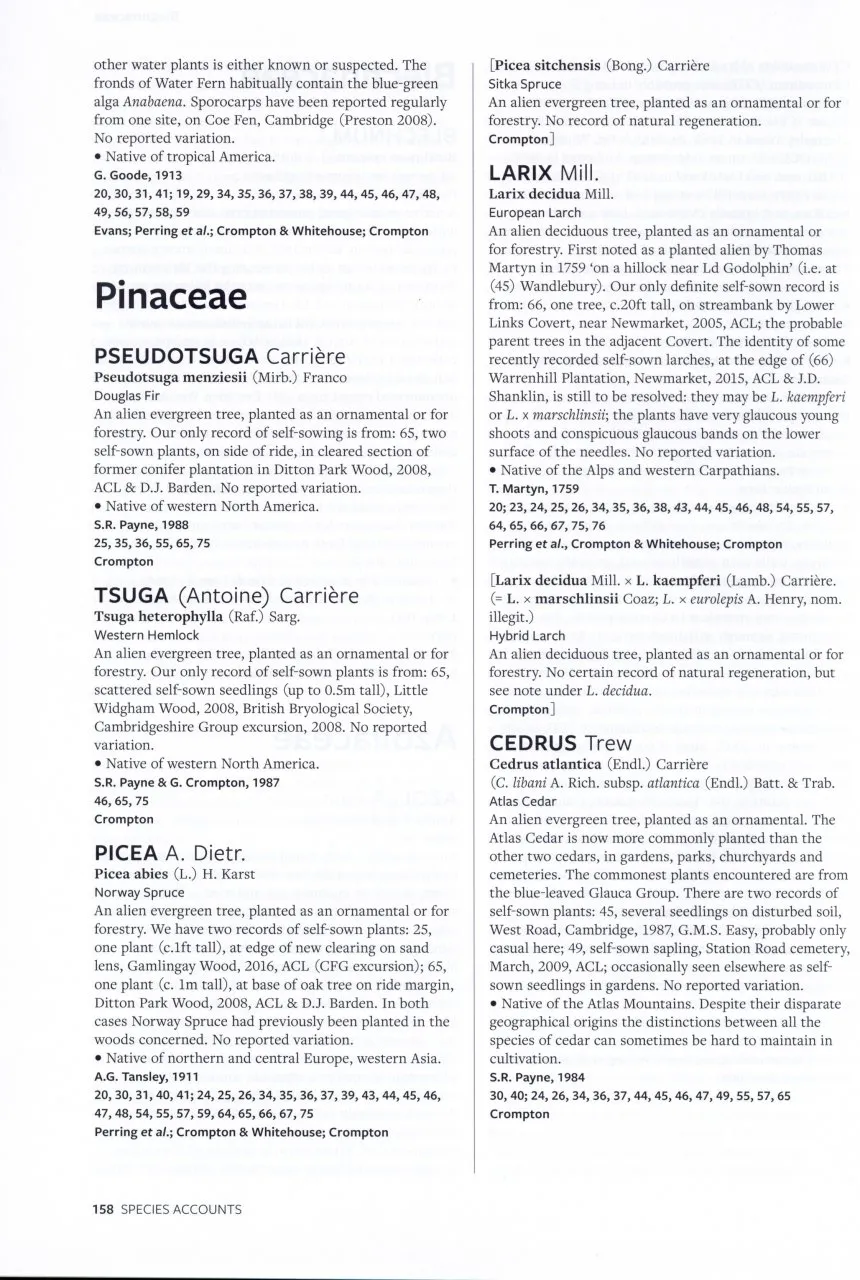

Given the trend in county floras towards giantism, one might have expected a whopper this time, but this one is off the scale. It is nearly a thousand pages long, for a start, and it weighs a ton. And yet, in the main part there are no pictures and no maps, either, but just dense columns of text. Illustration is confined to the first 144 pages, describing the natural features of the county, its best botanical hotspots and the long history of plant-recording there. The author has decided to dispense with the usual dot maps (and also the trend to record on an ever more minute – and increasingly pointless – scale), and simply to list the plant’s occurrence in 10km squares within the text. With the space saved, he chooses to concentrate on a comprehensive ‘discussion’, a minutely detailed historical record, of the fortunes of each plant.

To illustrate just how detailed, let us take one of Cambridgeshire’s special plants, the Pasqueflower. In the Perring Flora it took up just four lines. In this one the species is discussed in a considerable essay of about 1,700 words – more words than there are flowers, in fact. Its equally glamorous neighbour on Devil’s Dyke, the Lizard Orchid, receives about the same space. As for critical species, Leslie’s Flora includes 83 dandelions, 50 brambles, 28 hawkweeds, 36 cotoneasters, 35 goosefoots and, unusually (for Leslie is a specialist in the group), 15 goldilocks buttercups. In each case the entry includes the species’ status (introductions are divided into casual, established, naturalised or planted, all closely defined), habitats, distribution, variation, first records, 10km-square distribution and, in the case of species of special conservation interest, details of actual numbers of plants. The species sequence is set out as in the second edition of Stace’s New Flora of the British Isles (1997), i.e. before molecular advances messed everything up.

If all that sounds a bit breathtaking (and it is), this is a perfectly readable and well-designed flora, full of exactly the sort of information that interests field botanists. It is radical both in its exclusion of the usual maps and in its depth of detail. Like some other recent floras, it forms a kind of testament: to years and years of detailed recording, to the state-of-the-art of field botany, and to a clear intention on the part of the author to leave nothing out (Alan Leslie carries the weight of a great many famous and remarkable Cambridge botanists on his shoulders). While images of plants are fewer than in most floras, it includes four very nice botanical pictures of notable Cambridge plants, none of which I had heard of before.