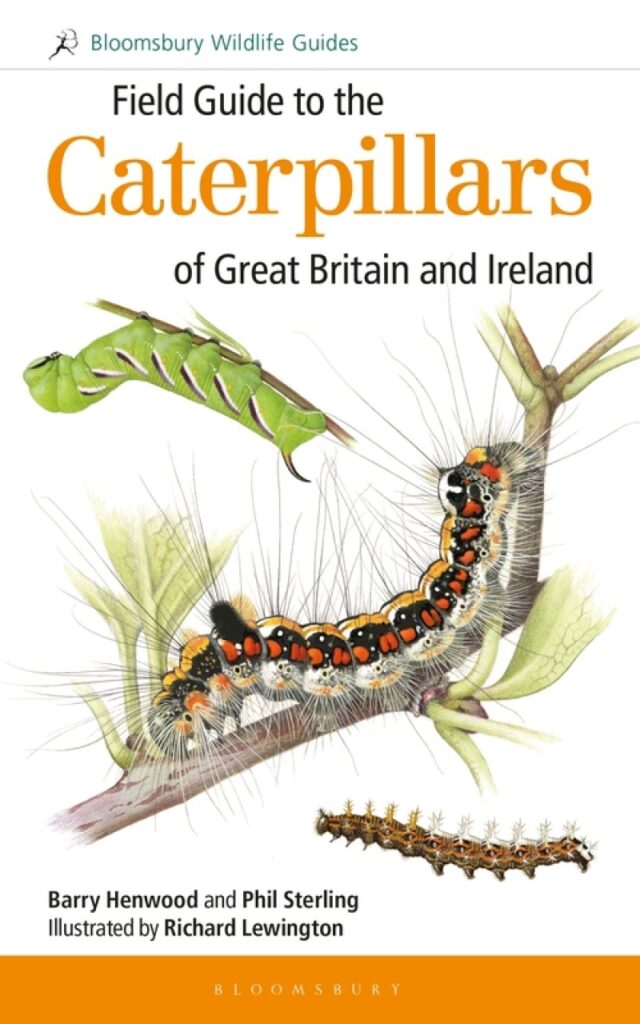

We are living through a golden age of insect field guides, and much of the credit is due to British Wildlife Publishing (BWP), begun a quarter of a century ago by Andrew Branson. This book, the latest in that stable, forms part of the Bloomsbury Wildlife Guides series, although the format will be familiar from the earlier BWP guides. The layout matches that of the Field Guide to the Moths of Britain and Ireland by Paul Waring and Martin Townsend, to which it makes a natural partner. Like it, the present book’s pride and glory are the illustrations by Richard Lewington. There are 828 of them here, all drawn from live specimens collected in the field, for museum specimens of caterpillars are usually too distorted or discoloured to work from. Some caterpillars are beautiful, some are bizarre, and some are downright ugly. But all of these drawings are perfect.

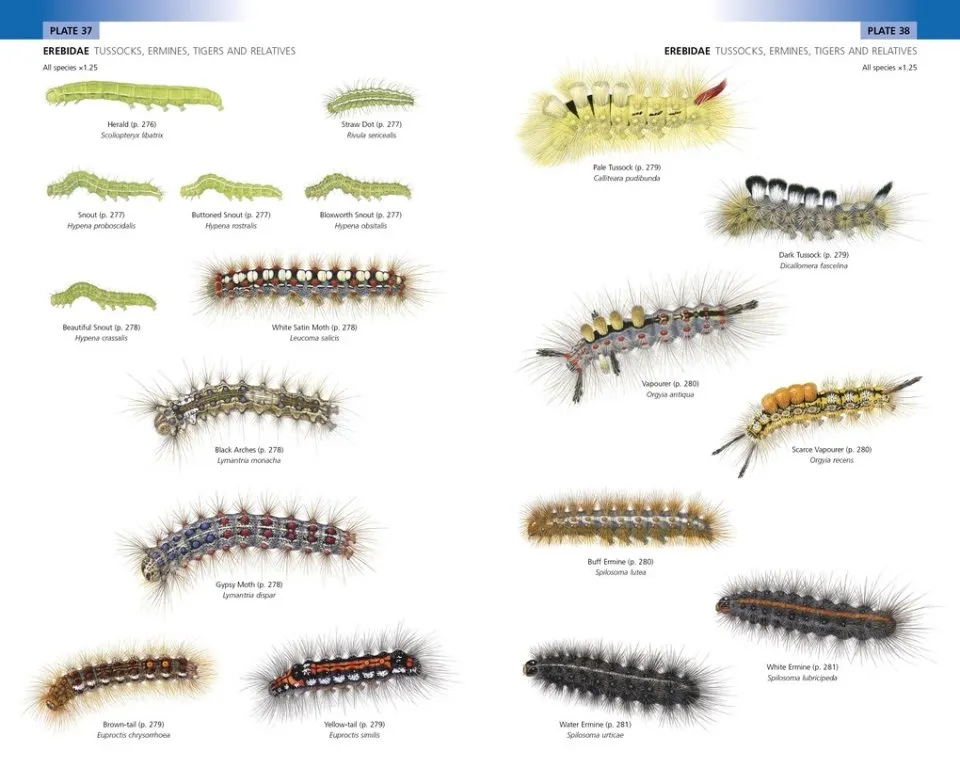

This is an eagerly awaited field guide. The previous guide to caterpillars, by Jim Porter, published in 1997,is long out of print, and it used photographs based on 35mm transparencies. That was quite an achievement for the time, but the present guide should be much easier to use and more likely to lead to a correct identification. Nearly all the breeding British and Irish species are pictured, the exceptions being the clearwings and swifts, whose caterpillars all look much the same, and three species for which caterpillars have not yet been found wild in Britain (interestingly, all three are small snout moths). Lewington’s drawings are of the fully developed caterpillar, the final instar, although younger stages are also shown in some cases. Most are drawn at ×1.25 magnification; butterflies are at ×1.75, as are the pugs. The smaller geometers are drawn at ×1.5, while the hawkmoths are life size. The illustrations occupy a single bank of plates in the middle of the book, with page references to the text. That at least makes comparisons easier, though it will require a lot of cross-referencing.

View this book on the NHBS website

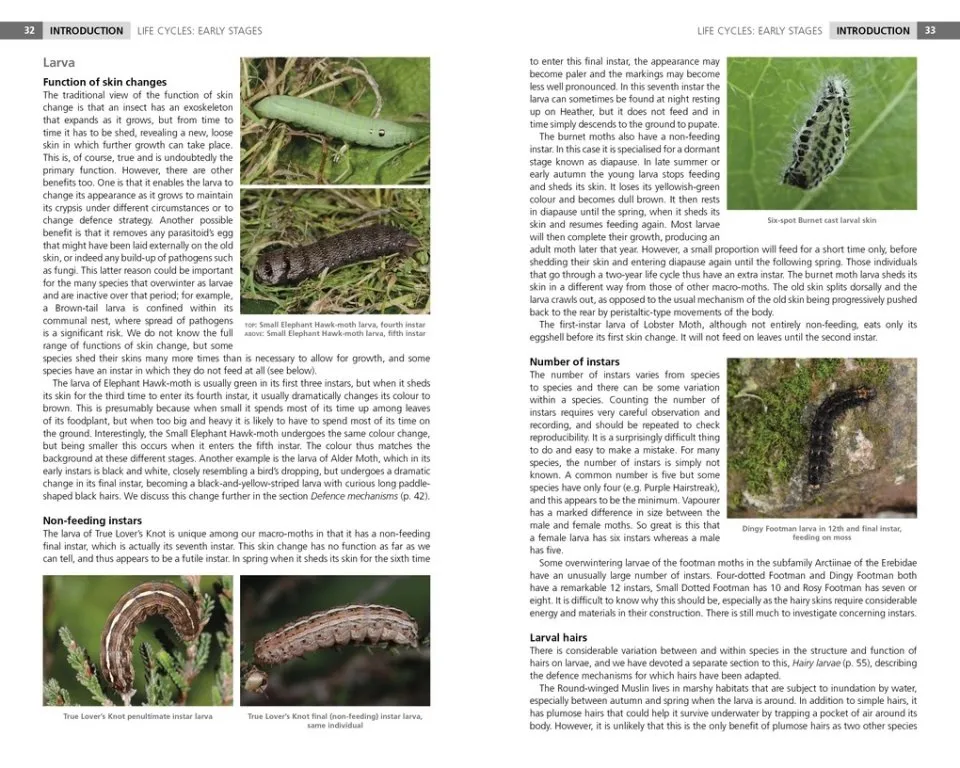

The text is excellent. An extensive and well-mannered introduction includes tips on searching for and rearing caterpillars, information on life-cycles and larval development, and details of foodplants. Particularly fascinating is the section on mimicry and other defence mechanisms, some of which seems to be new, such as the association of the Dotted Rustic with ants, and the surprisingly large number of caterpillars that contrive to look like little snakes. The camouflage of some species is so uncannily good that it is hard to make them out even in photographs. The species entries include field characters, foodplants, habitats, notes on similar species and how to distinguish them, and ‘field notes’, which in some cases, notably the clearwings, are quite extensive. Each is accompanied by an up-to-date distribution map. The page ends are colour-coded, and there is some back-of-the-book stuff: a checklist, a list of foodplants and their associated butterflies and moths, and separate indexes for English and Latin names. As a field guide it is hard to fault. It seems to me well-nigh perfect and a credit to all involved.

I hope and expect that this book’s publication will shift the focus from moth traps and adults to their younger stages (at one time some moths were better known as caterpillars than as adults, as will be obvious from their names). Perhaps the rearing of caterpillars will offer us one more thing we can do while we sit in our homes and wait for the coronavirus danger to subside.