This is the second volume of Geoffrey Kibby’s master class on the identification of larger fungi. The first (reviewed in BW 29: 72) was about the non-agarics – brackets, boletes, puffballs, club fungi and others, plus the large genera Russula and Lactarius. This new volume covers the white-spored, and some of the pink-spored, agarics, some 750 species in all, including the waxcaps and the large genera Tricholoma, Mycena, Clitocybe, Amanita, Pluteus and Lepiota among a myriad of smaller ones. A third volume will be devoted to the agarics with pink or dark-coloured spores.

View this book on the NHBS website

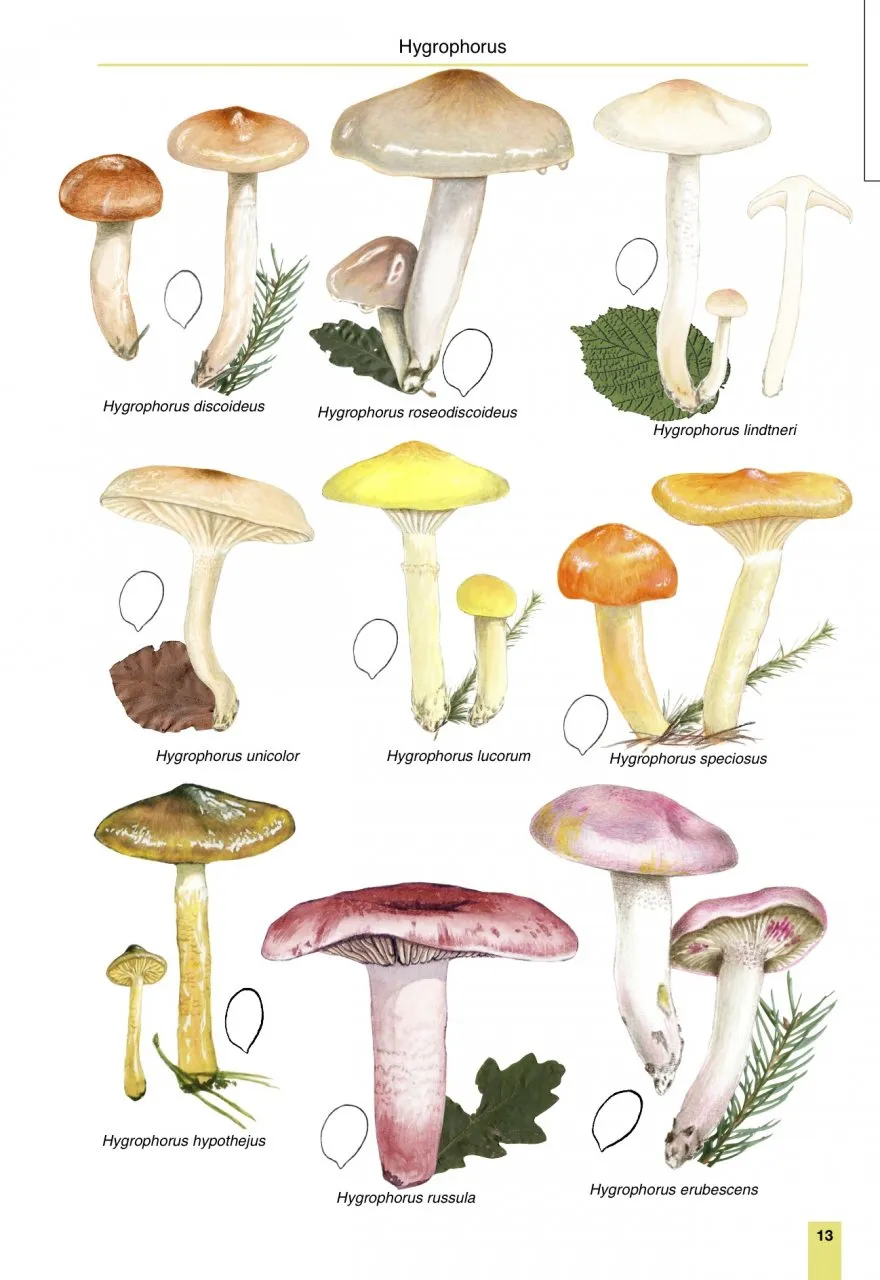

This second volume maintains the surpassingly high quality of the first. The illustrations are magnificent. Kibby reveals that all the drawing and painting was done by computer, using Apple’s iPad Pro and its Pencil 2 app (but I cannot imagine how he managed to capture the subtle colours and textures so well). In addition, he has designed and published the book himself. He modestly writes that, when the book is used in combination with a good set of keys in Fungi Nordica or Fungi of Temperate Europe, ‘I hope you will have a good chance of putting a name to your collections’ (in other words he is writing for fairly experienced field mycologists, but that is quite a lot of us these days). With that in mind, keys are at a minimum in this volume, and after a short, well-illustrated introduction (there is a more general introduction in Volume 1) we dive straight into the species accounts and the matching illustrations on the opposite page. This is the fullest treatment available of white-spored agarics in a single volume, and it is clearly the work that the author wishes he had had to refer to in his youth, but did not. Spore shapes are shown as well as the whole fungus, and, where relevant, other diagnostic features such as substrates, or a leaf from a mycorrhizal partner, or highly magnified cap cuticle, as well. Many of the species illustrated are rare – or at least rarely recorded – and a minority are foreign (though some of them may well be here unrecognised).

For the text descriptions, each visible part of the mushroom is run through – cap, gills, stem, flesh, spores. Proper attention is given to diagnostic scents and tastes, though I suspect that our noses differ; Kibby suggests that Tricholoma sulphureum smells ‘gas-like’, while I would suggest that the experience is more like sticking your nostril right over the tap and turning on the gas. His Clitocybe odora is ‘slightly anise-like’, but the chef to whom I once sold this species told me it knocks star anise clear out of the ring. Kibby’s Echinoderma aspera smells ‘rather unpleasant’; mine stinks like a burnt rubber tyre (though I quite like it). Anyway, you get the gist; Kibby is relatively restrained (though I look forward to his take on stinky species of Inocybe and Cortinarius).

As I say, reasonably experienced field mycologists will get the most out of this guide. Kibby does not use English names except where they are well established (though he does tell us what the Latin names mean). He does not care whether a species is edible or not, but he does mark the more notorious poisoners with a red cross. Like all mycologists, he never says oak or birch but Quercus or Betula. We say ‘farinacious’ when we mean smelling of raw pastry; or ‘raphanoid’ instead of smelling like a radish; or ‘nitrous’ when a fungus reminds you of the smell of bleach or swimming pools. This resistance to normal English is part of mycology’s tribal ethic; its roots lie in scientific internationalism.

I do not know how many copies Geoffrey has printed, but if you want a copy of the best field guide to fungi ever made you should probably make haste.