For those interested in orchids throughout Europe, rather than just those of their own country, it has not always been easy to find just the right field guide for the job. This wholly new guide to the orchids of Europe and the Mediterranean is a substantial tome that clunks through the letterbox at about 1kg. Is it just what European orchidophiles have been waiting for? Well, yes and no…

The immediate impression is that it is comprehensive and lavishly illustrated, both of which are borne out by further study. The authors write that ‘all European and Mediterranean orchids are included in this field guide’, which is reassuring, though it does depend on your definition of species, and a number of other authors’ species are not included. It covers a huge area, nowhere precisely defined, but, if we assume that it is the greatest extent of the variable distribution maps, it covers Europe as far east as the Caspian Sea, and the whole of a broad coastal strip along the southern shore of the Mediterranean, thus including, for example, Israel, Georgia, Armenia and the northern parts of Africa from Morocco to Egypt.

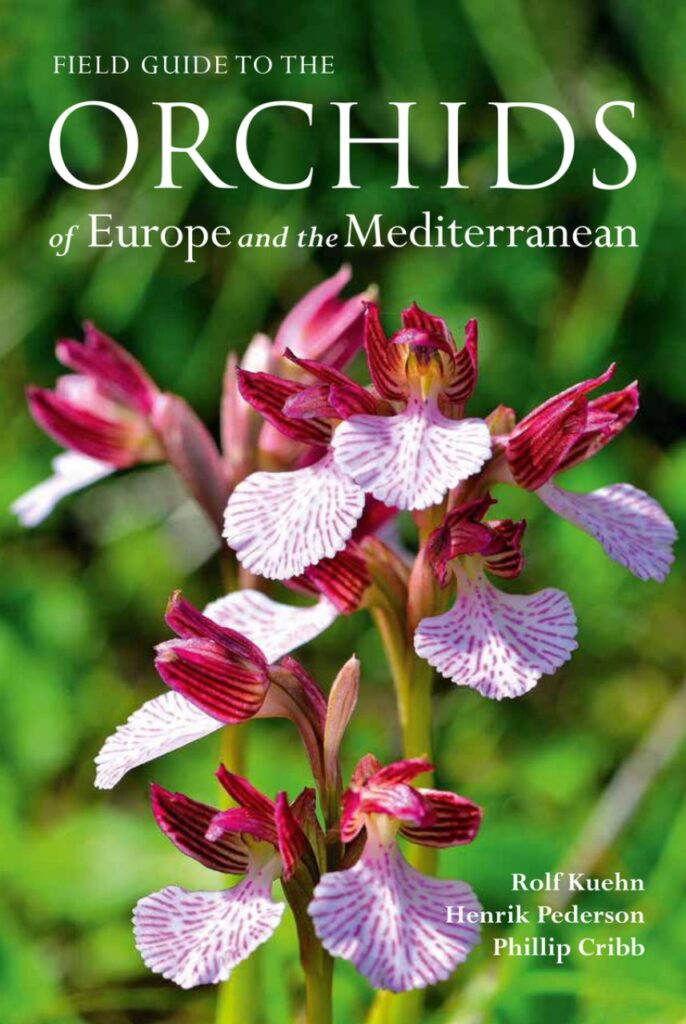

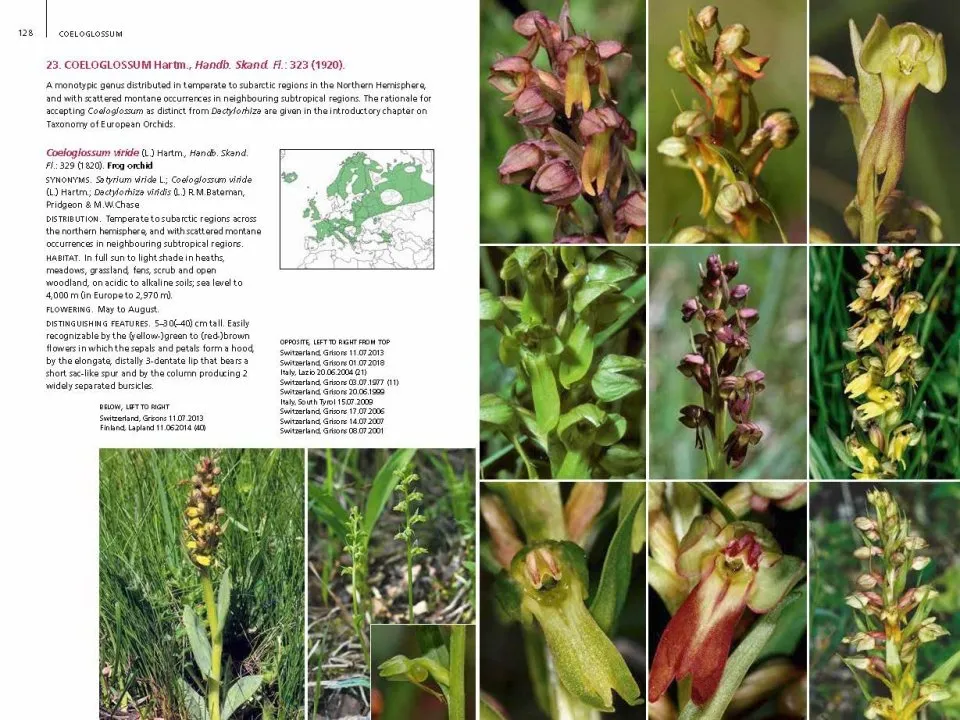

The authors indicate that this is essentially a photographic guide, with lots of pictures for each species showing the variability. These are generally clear, and large enough for the reader to see the detail. Then, under each species or subspecies, there is a section entitled ‘Distinguishing features’ which should help you to confirm or reject your initial diagnosis. There are no keys at all, and I think that this is such a pity. For small to medium-sized genera, such as Epipactis or Dactylorhiza, this would be the ideal way to get close to an answer. For the larger genera, notably Ophrys, this could help to bring down the number of possibilities, and perhaps lead you to groups within the genus, where there could even be further keys. Keys may not suit everyone, but without them you are left to work through the photographs. Suppose that you have an unknown Ophrys in Greece. Initially, you need to check through about 120 pages with over 1,000 photographs, from which you might get a shortlist of, say, six to ten species or other taxa on scattered pages. These may or may not be resolvable to species by using the maps and textual details, but in any event it is a long process. And the unfortunate thing, without keys, is that you learn very little each time about what the basis for separation of species is.

View this book on the NHBS website

Now, as anyone with an interest in European Orchidaceae knows, identification of orchids is quite different from the identification of other plants, both botanically and culturally. The polarisation of ‘lumpers’ and ‘splitters’ is here at its greatest. The authors of this field guide, might reasonably be classed as lumpers: previously named species are frequently now classified as subspecies of another species, although many former species have disappeared altogether. This may (or may not) be more taxonomically appropriate, but it does not make life easier for the simple field botanist. The species or subspecies are no easier to separate, and the names are harder to remember.

In the present book I find some of the authors’ decisions about species, and the use of particular names, hard to understand. A rather undistinguished and limited-distribution version of Elder-flowered Orchid Dactylorhiza cantabrica, for example, is described as a separate species, even though arch-splitter Delforge gives it no mention (it was described first by one of this book’s authors – I wonder if that was a factor?), whereas the pretty and distinctive Troodos Orchid Orchis troodii, recognised by most other authors, no longer merits the status even of a subspecies or variety here.

Coming closer to home, for our Southern Marsh Orchid Dactylorhiza praetermissa they use the name D. majalis ssp. integrata, even though neither Stace (Edition 4) nor Kew’s Plant List (www.theplantlist.org) uses this name. I could not help noticing that this new name’s authority is also one of this book’s authors, but it does not seem to be in general use elsewhere.

For any book of this nature, you have to look at the competition, and really there is very little. The most recent edition of Delforge, Orchidées d’Europe, published by Delachaux & Niestlé, dates from 2016 and is available only in French (and it is certainly not without its faults). Other books are much older. If you are mainly a visitor to one country, it would be worth seeking out more local guides to reduce the number of species. But if you travel widely through Europe in search of orchids, then this is the book for you – it is well illustrated and good value, despite its shortcomings.