This book made me think. Many writers of the current decade have bemoaned the loss of nature, presented a variety of anthropogenic reasons for the decline (not only in species but also, importantly, in abundance), and hinted at what a more positive future could resemble if we do the right thing. This template makes very straightforward reading for someone like me, who has worked in nature conservation for 40 years. Ben Macdonald’s thesis, on the contrary, is not straightforward at all, and challenges much of the received wisdom about how to bring back Britain’s birds.

The book charts a history of the British landscape, starting with what it was like before humans arrived – a very natural Britain. Ben’s take on the time since then – the Anthropocene – is subtitled ‘The killing of the countryside’. Decade by decade he works through the changes we have wrought: the loss of strip-farming and margins during the 1760s; the growth of hedges in the 1790s; the draining of the fens during the 1800s; the loss of scrubland controlled by large herbivores; the hunting of big birds across open landscapes as people and sheep took over; and the demise of seabird abundance, portrayed by the extinction of the Great Auk.

View this book on the NHBS website

By the time we reach the 20th century, forestry and agriculture are having a devastating effect on Britain’s birds. We have heard these arguments many times before, but Ben injects real catch-your-breath views about what we have lost: Cirl Buntings chattering on Wimbledon Common; Swifts nesting in Abernethy’s old-growth pines; and the car windscreen ‘splat test’ as a measure of insect abundance. Later, my organisation, the BTO, comes into the spotlight. It is widely recognised that the BTO Atlases of the 1970s onwards have demonstrated changes in bird populations in Britain on a national scale. But in Ben’s passage, subtitled ‘Recording extinction’, we get a sniff of his opinion that current conservation effort is failing Britain’s birds, much like Mark Cocker’s view that most organisations have been fiddling while the British countryside burns (literally, in some cases).

So, what to do? The first challenge is to own up to where we are, and to stop pretending that the situation is as bad all across Europe. Ben gives us statistics on losses – birds such as Wrynecks, Red-backed Shrikes and, of course, Turtle Doves – here in the UK compared with other European nations, some of which are also heavily industrialised. Second, let us get out of the ‘crowded island’ syndrome and admit that we have the space. After all, ‘wilding’ the countryside and ‘landscape-scale’ conservation are the latest buzzwords, appearing even in the Government’s 25 Year Environment Plan. And, third, we have to remember the role of the large herbivores, the landscape architects that have been shown to generate diversity at Oostvaardersplassen and Knepp. But there is one conservation tool that Ben believes we should rethink entirely: reintroductions.

For me, this is the most interesting element of his argument, and I am not sure of the reliability of the evidence used to support the diversity of reintroductions that are advocated. Ben’s view is that local extinction brings a loss of birds’ memories, and, once that happens, the species involved are unlikely to return unaided. Hence, Ben argues, we should focus on reintroductions, which should be much more widespread and involve not just charismatic mega-birds, such as White-tailed Eagle and Crane, but trickier species such as Wood Warbler, Willow Tit and Cirl Bunting, the last of which has already been successfully moved from Devon into Cornwall by the RSPB.

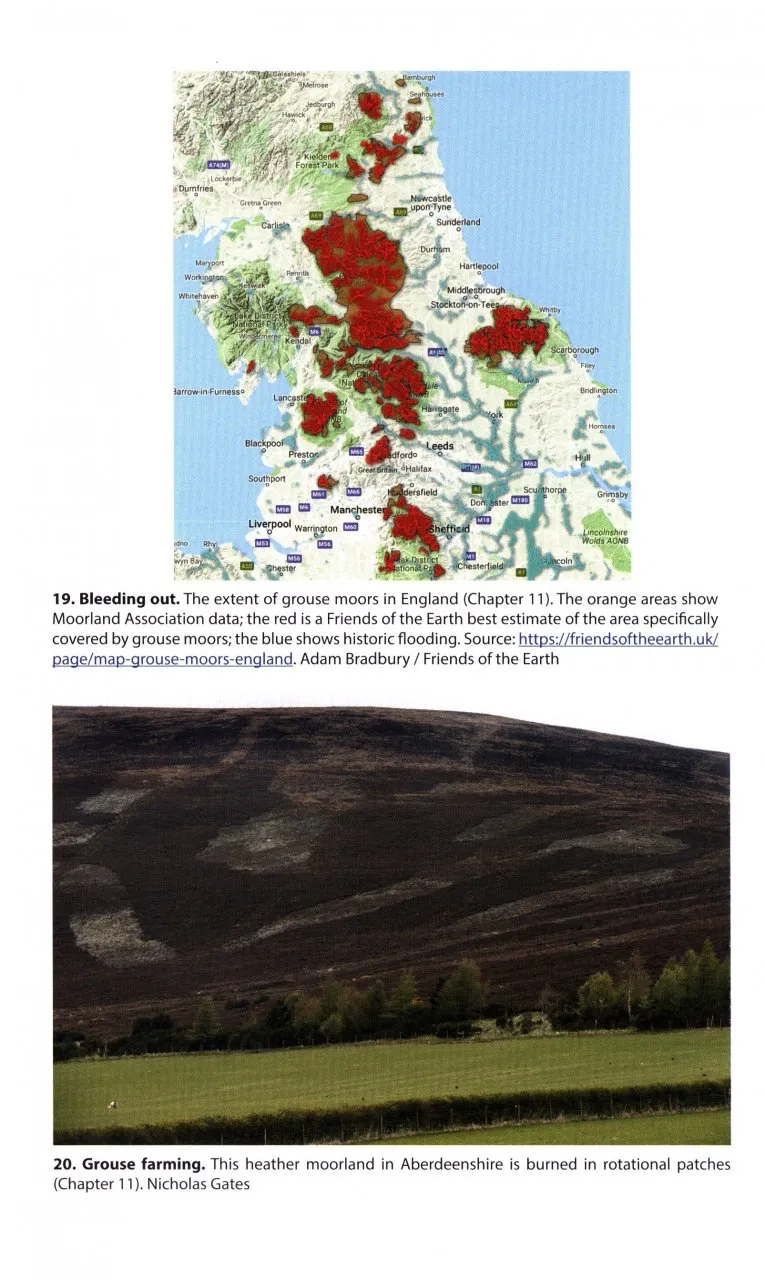

Following this is a series of views about how to restore the landscapes that our birds need. The National Parks come in for some restructuring (in line, interestingly, with what the Government’s adviser, Julian Glover, has said in his recent report on designated landscapes), the wild-deer estates of the Scottish highlands play their role, the forests are rewilded, our urban cityscapes are left messy, and the moorlands of England and Wales become golden, purple, and popular among human visitors. There is a sense here that the polarised fight which we see in action in the English uplands could, in Ben’s eyes, be solved more subtly by championing European-style hunting.

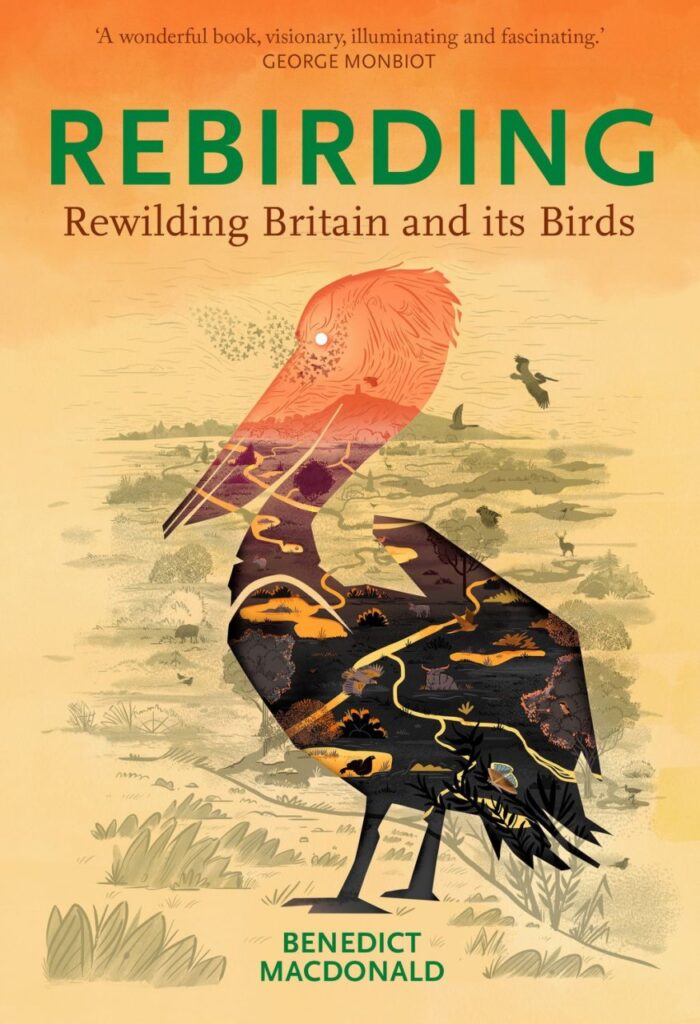

This book’s cover is dominated by an arresting image of a pelican. It is this species that provides an icon of what could be possible in the rewilding of Britain and its birds. If we get the landscapes and waterscapes right, there is, Ben argues, ‘Pelican possibility’ (it is probably just coincidence that this book arrived as Britain’s rare birds committee accepted the first record of a wild Dalmatian Pelican in Britain for centuries!). Rebirding certainly provides food for thought, in any case, and deserves to be read by those interested in a more natural future.