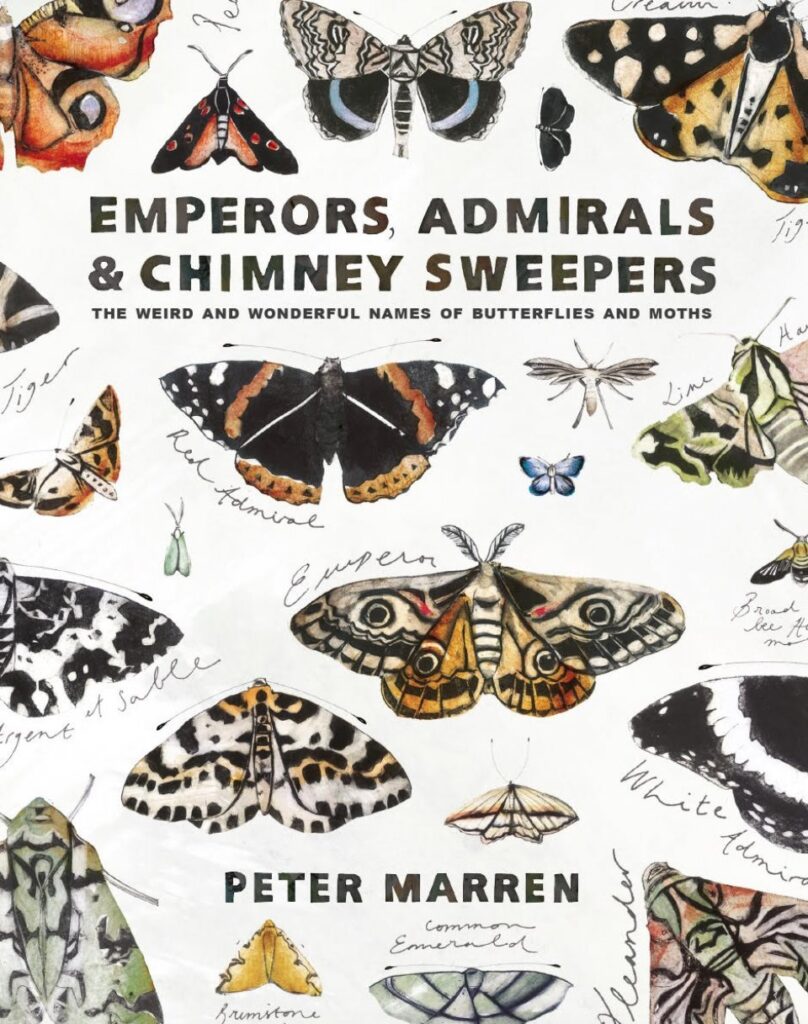

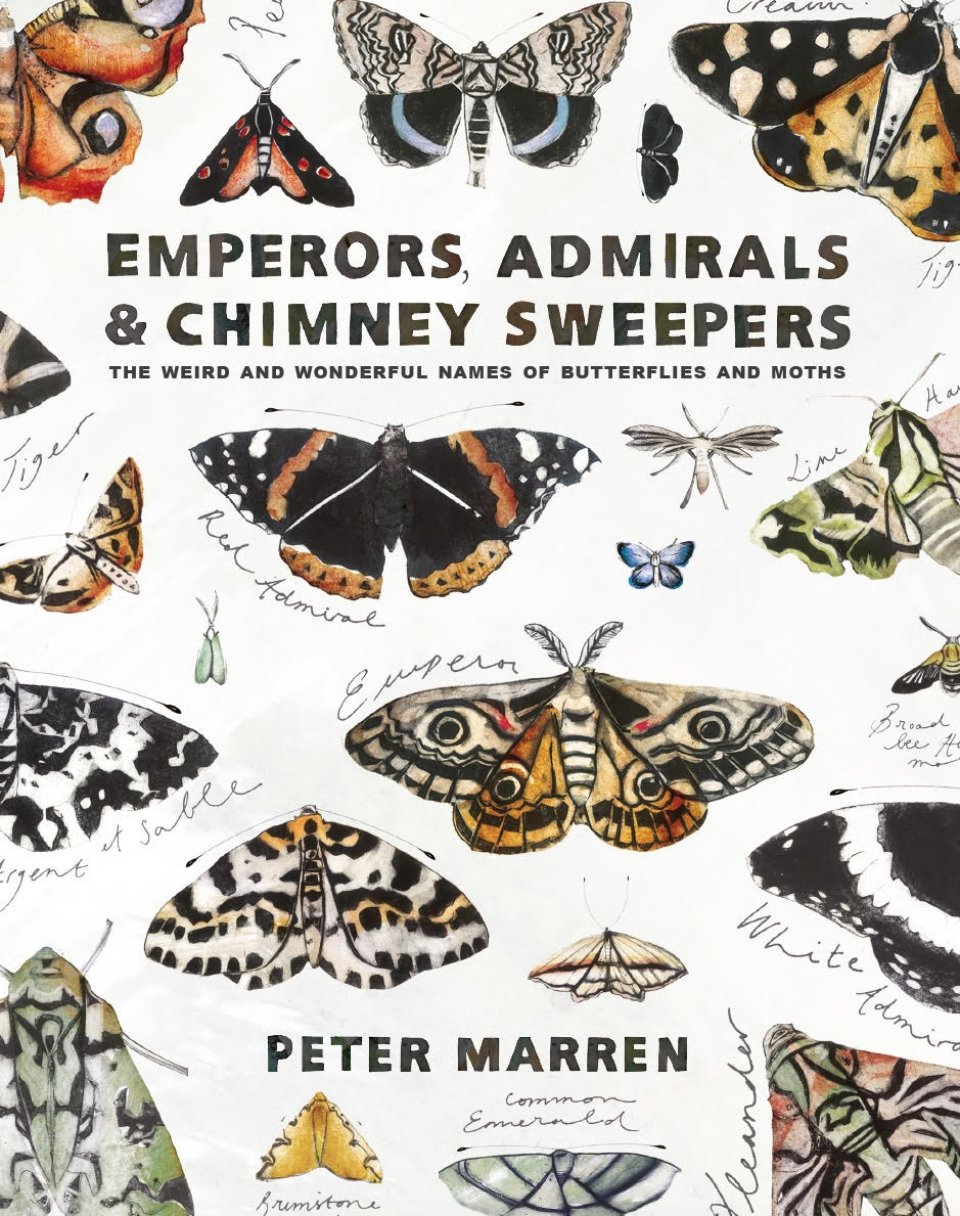

There are some books that could have been written only by one person and this is one such. Who else but Peter Marren could combine such deep expertise on moths and butterflies with such a wide-ranging knowledge about the origins of their wonderful names and the lives of the characters who invented them or appear in them. Who else, for example, could have written this comment on an obscure micro-moth:

The cruellest joke in entomology was played on Ottmar Hofmann, a blameless nineteenth-century German physician and an authority on very small moths. Other entomologists have been honoured by colourful, boldly marked, feisty species. Hofmann got the Brown House-moth, a scurrying nuisance of less-than-clean places. Worse, they named it Hofmannophila, or ‘I like Hofmann’, which is dangerously close to ‘I am like Hofmann’. Its species name is pseudospretella, or ‘false and despised’. Poor old Hofmann.

The whole book is a veritable treasure-trove of such curious and fascinating knowledge, a thesaurus where entomology is stored alongside etymology and both are enlivened by history and biography. Marren is the genial curator of this unique collection, and he offers here a guided tour in his usual learned but conversational style.

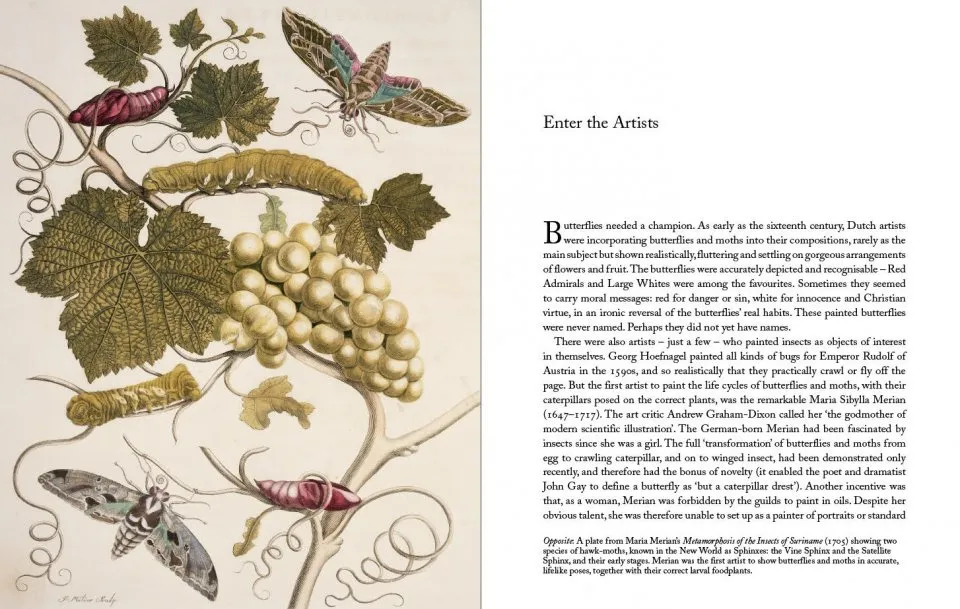

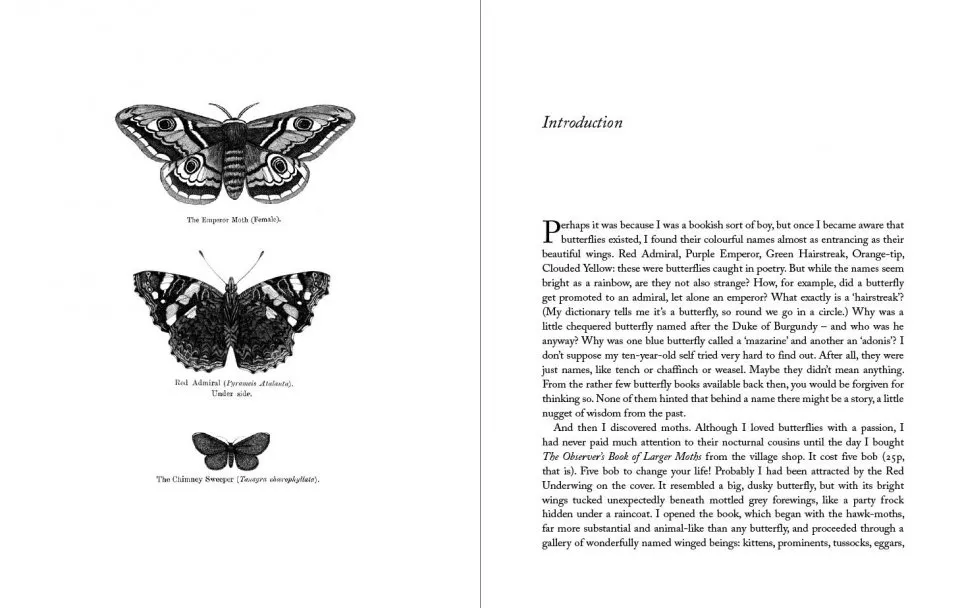

The book begins with a long but very readable introduction on the history of our interest in butterflies and moths, from the ancient world through to the modern day. We learn of: the English naturalists who first described and named the different species (such figures as Thomas Moffet, John Ray and James Pettifer); artists and Aurelians who popularised them (Maria Merian, Benjamin Wilkes and Moses Harris); the great taxonomists who gave them their Latin/Greek scientific names (Linnaeus, Fabricius and Hübner); and, finally, more recent collectors, such as the obsessive Ian Heslop, who have at last – though controversially – been awarding common names also to the ‘tinies’, the 1,627 (and counting) micro-moths on the British list. At the end of the book there is a very useful set of tables that list all these evolving English names and their variants.

View this book on the NHBS website

The core of the work is an A–Z section explaining some of these weird and wonderful names and their history. It is arranged as an alphabetical series of topics or categories which group together different names. So, ‘Birds’ includes the Magpie Moth, the Phoenix, the Hummingbird Hawkmoth and, more speculatively, the Slender Brindle Moth (whose Latin name is scolopacina, suggesting a possible connection with Scolopax, the Woodcock); while ‘Doubt and Confusion’ brings together those enigmatic moths splendidly entitled The Suspected, The Confused, The Doubtful, The Anomalous and The Uncertain; and if you want to go further in this direction there is always the section ‘Meaningless’, where even Marren cannot explain what the scientific names Bena, Tyta and Daraba could mean (are they possibly a firm of solicitors?), though he raises the deep philosophical question of whether names have to mean anything at all. You can read these topics in any order and they are ideal for just browsing. If you want to find if a particular moth or butterfly is mentioned in one of these mini-essays, you can do that easily through the indexes (Latin and English) at the end of the book.

There is a magic in these names. How wonderful to know that we have among us such creatures as the Setaceous Hebrew Character, Flounced Rustic, Pebble Prominent, Frosted Orange, Merveille du Jour, Powdered Quaker, Dingy Footman and Poplar Lutestring. You can spend hours of pleasure just reading the indexes and rolling these names around on your tongue. Even better, though, is to dive in and learn, for example, that ‘Setaceous’ means ‘bearing a bristle’ and refers to the white line around the ‘character’ mark on the wing. Marren adds the tidbit that ‘A well-known Jewish moth collector, the Baron de Worms, whose thinning hair stood up in stiff tufts, was affectionately known by his fellow moth-hunters by that name’. Not many people know that… There is a wealth of such anecdotes and surprising information in the book. Did you know which is the only moth to be named after a character in the Bible, the only butterfly to be named after a woman, and which two moths are named after the city of Manchester? It is all in here.

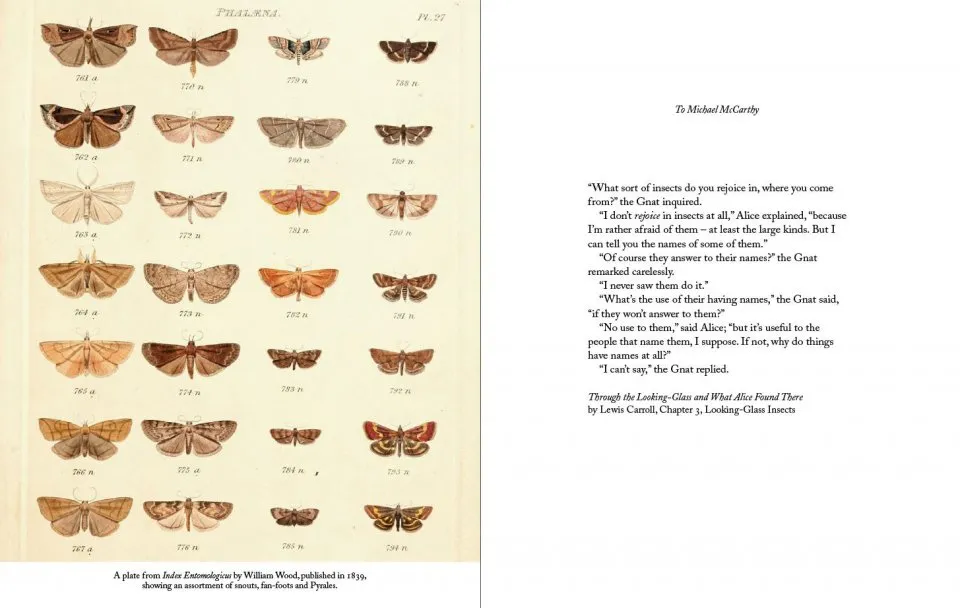

The publisher, Little Toller, branded this book as one of their ‘Field Guides’. I have been field-testing it against the catch in my moth-trap for some nights. The only trouble is that you become too interested in Marren’s text and forget about the more arduous problems of moth identification. Better to consult when you are writing up your notes afterwards and can also enjoy the many illustrations, the best of which are the ones taken from old hand-coloured engravings.

Peter Marren makes a generous acknowledgement to his only real predecessor in this field, the redoubtable Lt. Colonel A. Maitland Emmet, who produced a very scholarly work on the scientific names of moths in 1991. Like the original namers, Emmet had a remarkable grasp of classical mythology, which enabled him to identify many of the minor figures referred to in the often-opaque Latin names. His work remains an important point of reference for specialists, but for a more general audience is austere almost to the point of unreadability. Nor does Emmet deal at all with the English common names, where Peter Marren has been largely on his own. Marren’s real originality, though, is to bring together the art and the science to enrich and enlarge our whole experience of these wondrous creatures. It was said by August Strindberg, a fellow Swede, that Linnaeus was ‘a poet who happened to become a naturalist’. On the basis of this book and the rest of his astonishing oeuvre, I think that we can say in turn that Marren is a naturalist with the soul and imagination of a poet.