The first edition of Dobson’s lichen guide was published in 1979, so a lifetime of experience has gone into ‘Dobson 7’, and the author must be congratulated on his dedication to updating this guide to what is probably the most diverse, challenging and complex group of organisms. Mark Powell is given generous acknowledgement for his help in this latest edition, and has been bequeathed oversight of future editions as coordinating editor of a team of British Lichen Society (BLS) members. Powell has also added a section on lichenicolous fungi, and this is a tremendous boost from the previous editions – recognition of lichenicolous fungi is becoming more common now, and folk are frustrated by the lack of easily available literature to attempt identification, so the addition of 15 of the most commonly encountered species, with good photos and diagrams, is welcome.

The layout of this edition closely follows the 2011 version, but with significant updates. The Introduction is concise, and has incorporated recent changes in definition as to ‘what is a lichen’ (see BW 30: 155–156). The world of lichenology continues to amaze in the complexities that are unfolding through more detailed research into DNA and the use of fluorescence techniques. It seems that the act of putting names to species and assigning them to genera is in a state of flux, so where does that leave those who are taking up an interest in lichens? How useful is this latest edition of Dobson?

View this book on the NHBS website

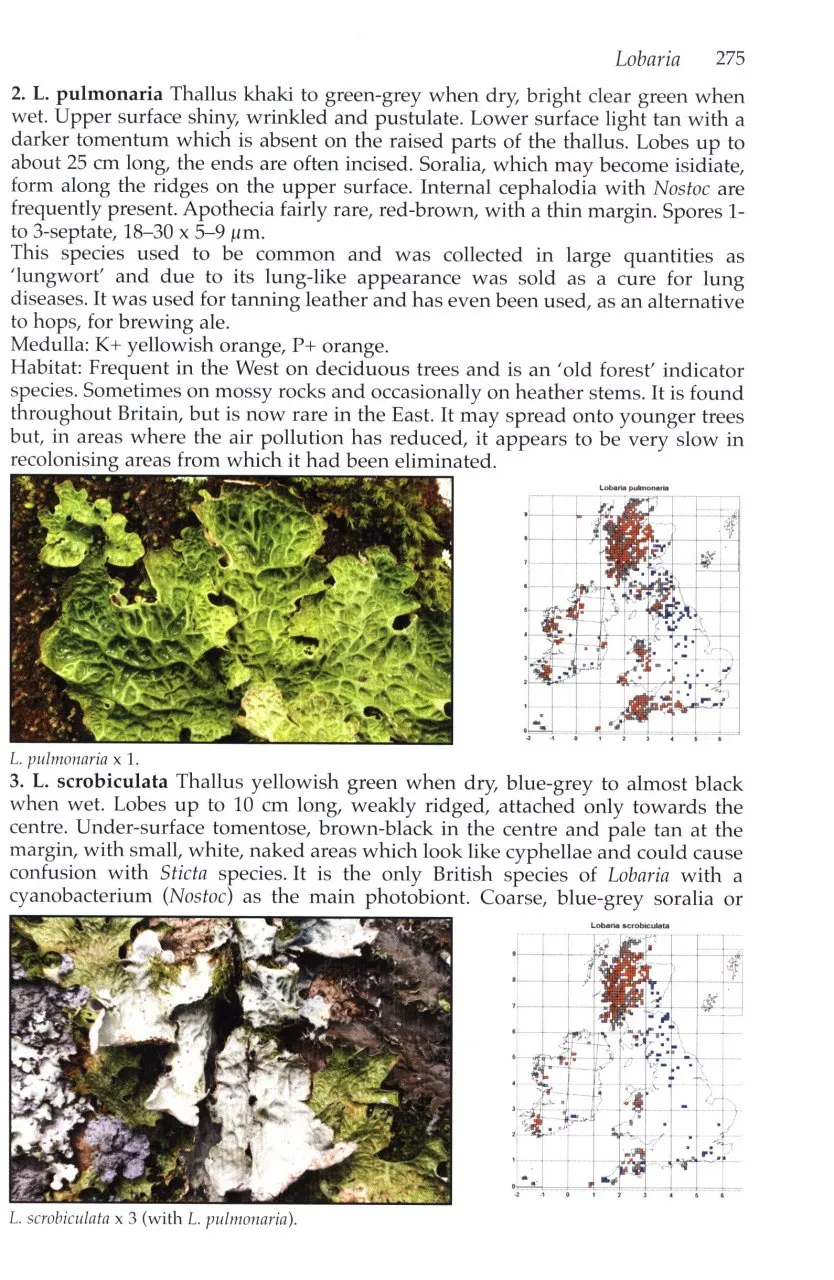

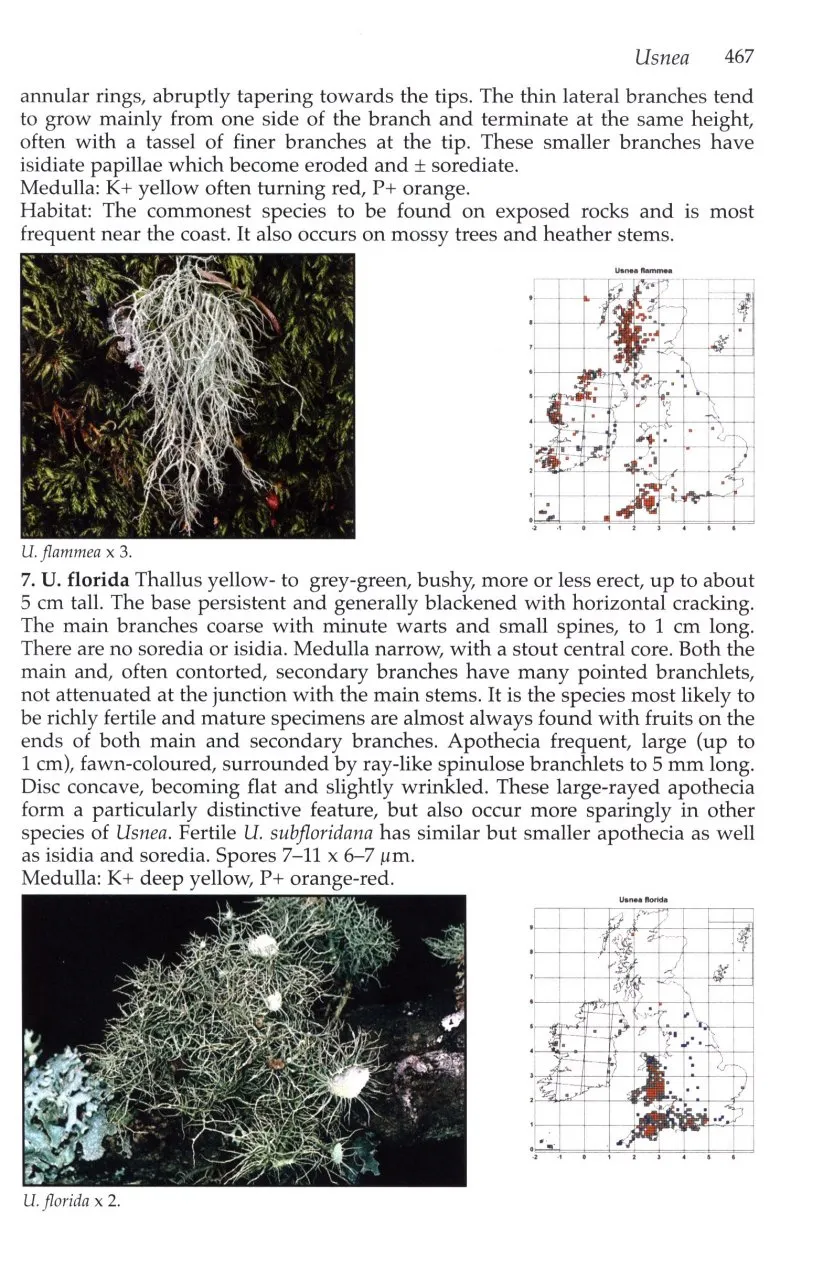

There is an awful lot packed into the 520 pages of this volume. In an effort to be as comprehensive as possible, there has been some compromise on layout, the index, for instance, seeming to run on from the glossary. But once one becomes acquainted with the compactness, it does become more comfortable to use and it remains the best available field identification guide for lichens in Britain and Ireland. Nearly every species has a colour photograph and a distribution map. There is much useful information on how to study lichens, including the use of microscopy and chemical spot tests. There are quite detailed and useful descriptions of the role of the photobiont (the algal partner), and information covering physiology, ecology, lichen communities, and the significance of air pollution.

Dobson 7 brings up to date many of the nomenclatural changes and includes useful cross-referencing to species and genera names that are ‘new’ since 2011. The brief etymology of each genus name is a nice touch which adds to the general interest, while another enjoyable feature, one which sets this book apart from other ID guides, is the occasional mention of uses, both current and historic, of some species. In the account for Evernia prunastri, for example, we learn that, among other things, it was used as a fixative for perfume, as wadding in shotguns, and by Long-tailed Tits as a favoured material for nest-building.

So, what are the snags? To some extent, the appeal of the book is that nearly every species is represented by a colour photograph, but the quality of some photos could be better. One would not, however, want to use any identification guide in isolation, and checking online or in other books will help if there is any doubt. The main worry, though, is that the scale information (×2, ×4, etc.) appears incorrect in many photos. Hence, as an example, the scale attached to Peltigera membranacea says ×4, yet the description of this species gives the lobes as ‘up to 3cm wide’. When I measured the lobe width in the photo, I got 1.5–2cm, so a scale of ×4 would mean that the lobes would be only 0.375–0.5cm. This is clearly misleading. Unfortunately, the scale for many foliose species appears inaccurate, suggesting that the lichens are much smaller than they really are. This problem was mentioned in the 2011 review of Dobson 6 (Coppins 2012), and it is a shame that it has not been corrected.

The distribution maps, based on data provided by the BLS, are useful and include differently coloured dots to allow you to pick out records made within the recent 2000–2017 period. Dobson clearly spells out caution in interpreting these distribution maps, however, and validation is required if you want to send in a record of what you think may be an unusual or rare lichen, or a species in an unusual locality. You would need a hand lens to see the full detail of the maps, but no lichenologist should be without this essential tool, anyway!

I am slightly disappointed with the selected bibliography, which is virtually unchanged since the 2011 edition and includes no mention of the excellent FSC fold-out guides or the equally excellent Plantlife lichen guides. As with any group, it is useful to be able to consult more than one book.

I was disappointed also that so little mention was made of the BLS. There is a small paragraph tacked on to the bottom of the bibliography which does briefly mention membership of the BLS, and the BLS website. I do feel, however, that, as the BLS can offer so much to anyone interested in lichens, more prominence in the book would be useful. It may have been worth mentioning also some of the lichen courses offered by the Field Studies Council. Judicious and intelligent use of the web can provide sources of help to those starting to take an interest in lichens, and there are also some useful blogs, and the BLS’s Facebook and Twitter pages. But, certainly, there is nothing quite like Dobson 7.

Reference

Coppins, A. M. 2012. Book Review. The Lichenologist 44(4): 563–564.