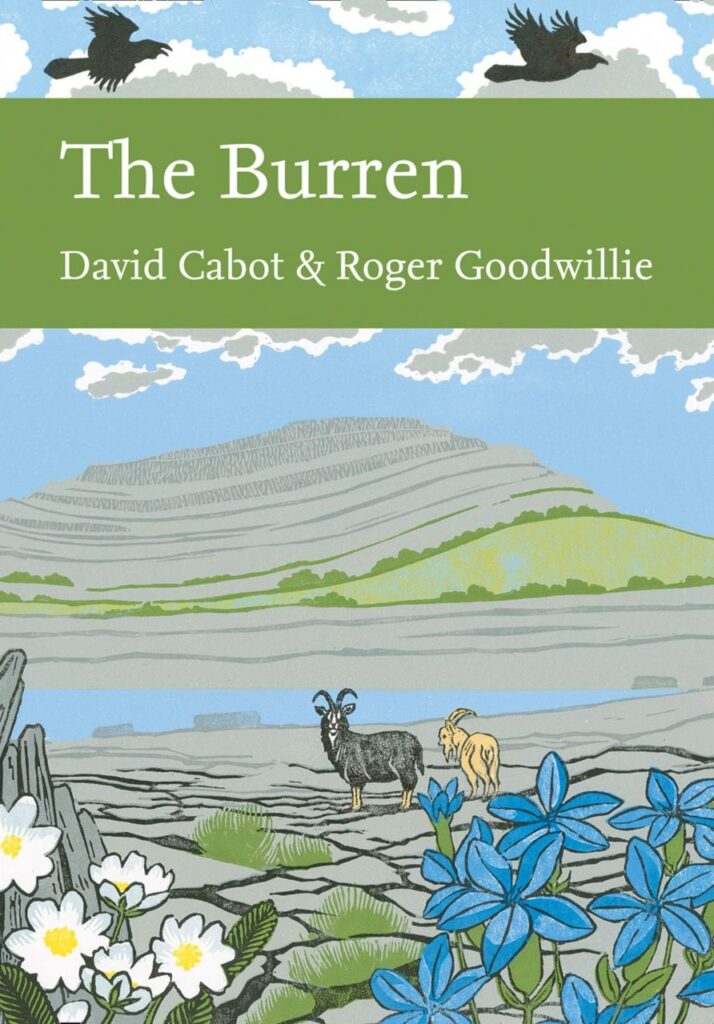

Several New Naturalist volumes have referred to the Burren, that swirl of bare limestone rock to the south of Galway Bay, including David Cabot’s own Ireland. But this is the first to do the area full justice, and indeed the first volume in the series to deal with a particular region of Ireland. It is also one of the best-presented New Naturalists so far, exceptionally well illustrated with colour photographs, most of them commissioned specially and by Fiona Guinness. It is very strong on botany and plant ecology, but does not neglect animal and insect wildlife nor the place’s history and the factors that make it unique (and for once the word is justified). The book is detailed (with 460 pages it would be) but readable, and between them the authors cover the setting, the science, the way of life and every kind of plant, beast or beastie, with special reference to those characteristic of the Burren. Given that David Cabot is primarily an ornithologist, it is surprisingly light on birds, but that is because birds are its least exceptional aspect.

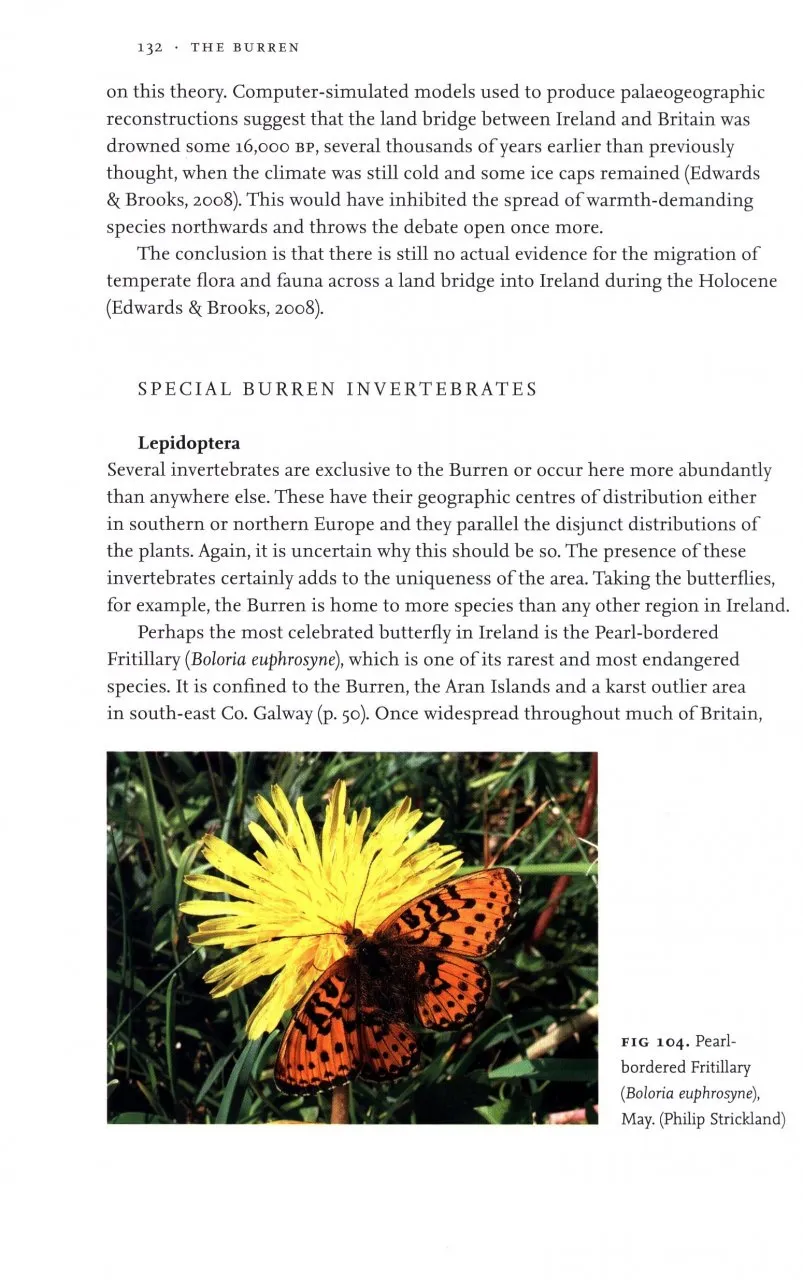

From the road, most of the Burren looks quite bare: a moonscape of hard, pale, fissured limestone. As Cromwell’s man Edmund Ludlow put it, there is not water enough to drown a man, nor trees to hang him from, nor earth to bury him in. But appearances are misleading, and in fact only 20% of the area is rock; the rest is grassland, scrub, coastlands and that quintessential Burren habitat, winter-wet lakes known as turloughs (on which one author, Roger Goodwillie, is an authority). The climate is mild and wet, virtually frost-free but with 60 inches (c. 1524mm) of rain per year, despite which visitors often experience prolonged sunny weather. It is a meeting place for species from different places. Plants from the Arctic and the Alps rub shoulders with others from southern Europe. There is a fine range of invertebrates, too, including two pretty moths, the Burren Green and Irish Annulet, found nowhere else in the British Isles, and the mysterious Land Winkle, and this is the only place in Ireland for Pearl-bordered Fritillary, Brown Hairstreak and Wood White.

View this book on the NHBS website

The last chapter, on the future of the Burren, takes us through the familiar labyrinth of designations, ‘programmes’ and ‘initiatives’, and, as usual, it seems impossible to tell how much difference, if any, it all makes. Farming has become marginal at best, and when grazing ceases scrub invades. Tourism meanwhile is on the rise, with around 10,000 visitors a year. Only a small area, around Mullagh More, is a National Park.

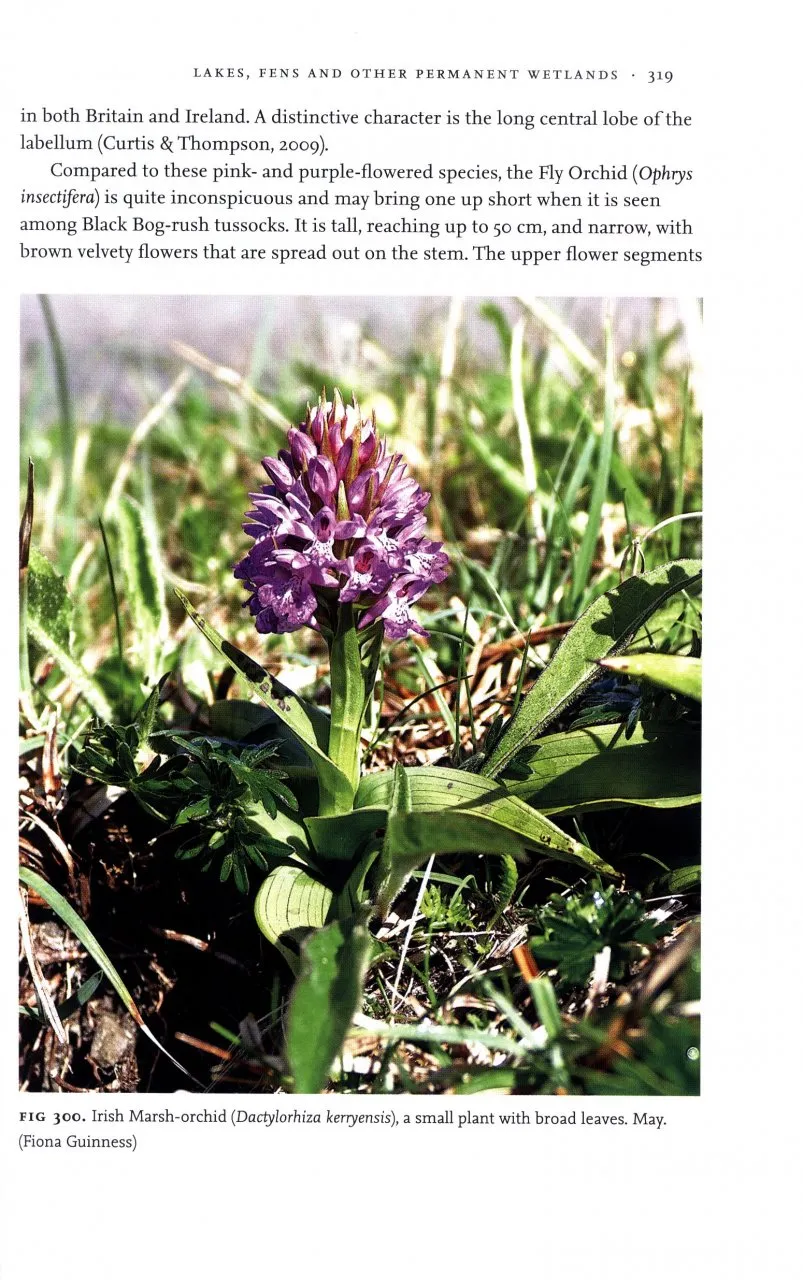

My criticisms of this book are minor. They got the wrong wood white on page 133, but got it right on page 237. Given the interest in them, I was surprised that there was not more on the orchids, especially the special marsh orchids, one of which (Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp. cruenta) is not even mentioned – and why not a picture of the beautiful Dark Red Helleborine growing out of a limestone fissure instead of the several images of Irish Eyebright and Shrubby Cinquefoil? I would not have minded learning a bit more about the remarkable fungus flora associated with the Burren’s wonderful carpets of rockrose and Dryas. It seems to be editorial policy for all species to be given initial capitals, even the most familiar such as Hawthorn, Hazel and ‘Red Fox’ (but not ‘ivy’ or ‘fairy shrimp’). This always looks odd to me, and no one outside the scientific community capitalises hawthorns and foxes. And I may have missed it, but I think that there should also be a health warning somewhere: when I was there, admittedly a long time ago, the turloughs swarmed with ticks and painful biting flies.

This is a fine addition to the series, and beautifully presented inside Robert Gillmor’s atmospheric linocut jacket with a well-balanced text and illustrations. It is the book which this wonderful place deserves, and one which will have many of us instantly planning an expedition to western Ireland.