Twenty-eight years ago saw the end of an era: the nearly 40-year reign of the then standard British Flora, Clapham, Tutin & Warburg (affectionately known as ‘CTW’), effectively passed with the arrival of Clive Stace’s New Flora. In spite of the best efforts of the late Peter Sell and Gina Murrell, whose five-volume treatment concluded in 2018, Stace has become the default taxonomy for Britain and Ireland, used by amateur and agency alike. New editions are greeted with a mix of excitement and trepidation: which well-loved old names will be lost? What new ones will I need to learn?

This nicely produced book, the first edition to be self-published, has seen perhaps the most comprehensive reworking of the text to date, with updates to keys, descriptions and distributions, as well as the addition of more than 200 species, subspecies and hybrids, five of which are newly discovered natives. Previously treated alien taxa not seen since 1999 have been removed, although they are retained in the keys. This may cause some confusion, but I think that it is a sensible approach. The additions have seen the book grow by 34 pages and yet it looks and feels more compact than its predecessors, which themselves have slimmed with each new reprinting.

View this book on the NHBS website

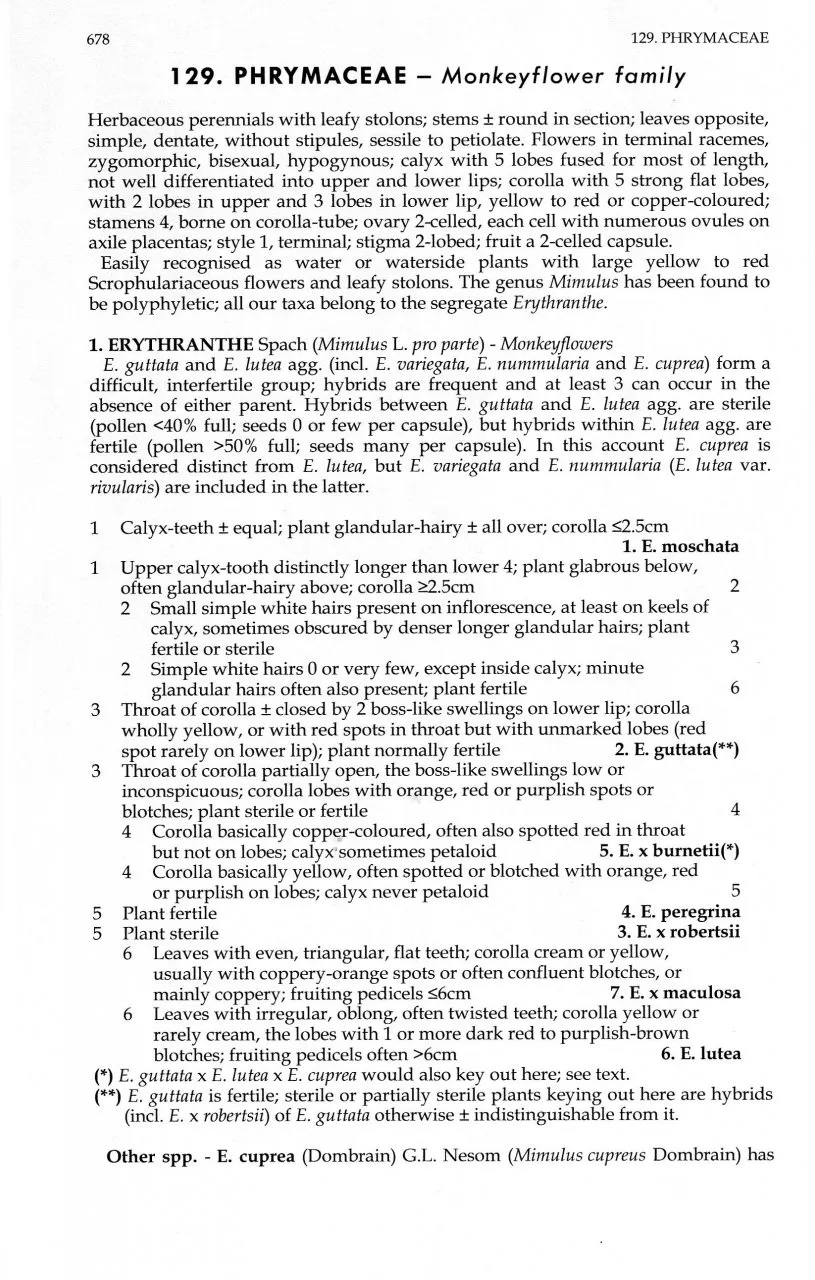

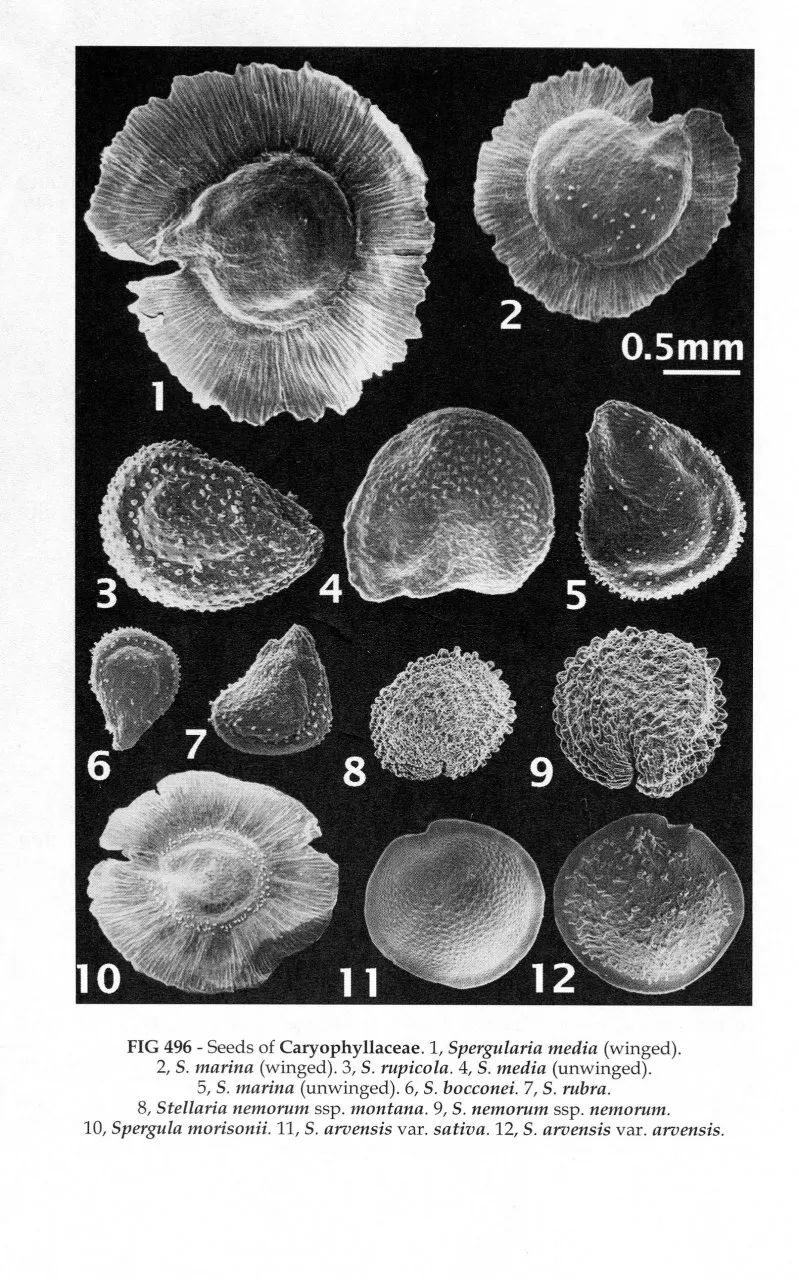

Stace has taken on board the most recent iteration of the Angiosperm Phylogeny group (APG IV), although not slavishly, but curiously he seems not to have followed most of the recommendations of the Pteridophyte equivalent, PPG I, published in 2016. This may lead to charges of a certain inconsistency, although his decisions, where elaborated, show the basis of his judgements. He has always defended the retention of some paraphyletic entities, although one, the Lemnaceae, has finally been sunk into the Araceae. The major changes taxonomically, though, are not at the familial level, where we are approaching greater stability, but at the generic. There seems to be a mood more generally against large genera: existing subgenera and sections now tend to be accorded generic status, and molecular studies have additionally revealed some apparently discrete groupings for which we currently have no morphological support, e.g. the shifting of the saxifrages Saxifraga nivalis and S. stellaris into a new genus, Micranthes. This interpretation of the molecular data has led to a host of common and widespread genera (e.g. Chenopodium, Aster, Gnaphalium etc.) being split into, in some cases, five or more genera, giving us lots more names to deal with. The one instance which bucks the splitting trend is the submerging into Lysimachia of the genera Anagallis, Centunculus, Glaux and Trientalis, although in several cases smaller genera have been subsumed into larger (e.g. Myosoton into Stellaria, Pisum into Lathyrus, Tetragonolobus into Lotus, Lens into Vicia, Conyza into Erigeron, Kobresia into Carex etc.). Will these changes stand the test of time? It is apparent to anyone from the CTW era that many of the ‘new’ names are returns, sometimes welcome, of familiar ones (e.g. Buglossoides, Cherleria, Logfia, Lycopsis, Reynoutria, etc.), reflecting more a change in philosophy than anything else. It will be interesting to see how some of the novel segregates fare, but in the meantime we shall all be obliged at least to be cognisant of the changes that are captured here.

With such a radical and personal reworking it is perhaps not surprising that there are elements that may prove contentious. I regret the decision made to treat the taxa within the Dryopteris affinis aggregate as subspecies, as I feel that this will hamper their recording and better understanding. Status and recognition matter and, with Stace’s taxonomy achieving such dominance, it is important that opposing views are heard and, where defensible, are picked up by the recording and conservation communities. I think, too, that it is a shame that the other critical groups of apomictic taxa are not also treated more fully in a work that sets out to be exhaustive elsewhere. These are minor quibbles, though, over what is an extremely comprehensive and usable work.

So, should you buy it? As with its predecessors, it is essential reading and, in truth, I suspect that most serious British botanists will already have it following pre-publication offers. If you do not already own a flora and have any pretention to study or identify British plants, then it is a must-have. The magnitude of the changes to names, plus the addition of the latest crop of garden and other escapes, also means that an upgrade from an earlier edition is not only worthwhile but probably a necessity.