To call this work an ‘atlas’ does not do it justice, as it is far more than that. It includes accounts of 104 species based on about 149,000 records. Unlike some distribution atlases, this one includes the whole of Ireland, which has 70 known species, and the Channel Isles, which have 63 species. Five families are covered, these being Hydrophilidae, Helophoridae, Hydrochidae, Georissidae and Spercheidae, the last two of which have just one species each. The identification of these families is covered by the RES Handbook, Volume 4, Part 5b: Keys to Adults of the Water Beetles of Britain and Ireland (Part 2). While many of the species are true water beetles, most of the subfamily Sphaeridiinae of the Hydrophilidae are associated with dung and decaying material, where they are often the most abundant beetles, while a few Helophoridae are entirely terrestrial and may be found in very dry habitats. Despite the challenges of identifying water beetles, they have been remarkably well recorded over many years, perhaps owing mainly to the long-established Balfour-Browne club and the existence of relatively good (for their time) identification works from the 1950s onwards. Evidence for changes in distribution and abundance is therefore often stronger than for most other beetles. It is noted that the non-aquatic species are less well recorded and hence the data perhaps do not reflect their distribution so accurately as they do for the true water beetles.

There are introductory notes for each family and detailed information for each genus. Each species account includes a map of the expected distribution at 10km-grid-square resolution, with two date classes, pre-and post-1980, together with some subfossil records. These maps are, of course, interesting in themselves, as many species have restricted distributions, but much more information is supplied in the text. For each species this is divided into four sections: taxonomy and identification, life-cycle, habitats and distribution, and natural enemies (where known). In effect, these provide complete accounts of the biology of the species so far as is presently known. Hydrobius fuscipes, split into three species in the latest checklist, is still treated as a complex because it was considered that more genetic analyses were required in order to establish exactly how many species there really are. In addition, Megasternum concinnum and M. immaculatum, for which individual maps would be misleading, are not mapped. For many people, the most interesting section in the species accounts is likely to be that on habitats and distribution. Together with the maps, this provides a very good indication of where to search for particular species. The information on taxonomy is detailed and complete, but of interest mainly to specialists, while the section on natural enemies refers mostly to laboulbenian fungi, nematodes and mites, which, again, are perhaps of limited interest to the more general reader. Nevertheless, the inclusion of such detail is to be commended.

View this book on the NHBS website

The accounts of scarce species comprise, naturally, those that are most immediately interesting. The map of the Lesser Silver Water Beetle Hydrochara caraboides, for example, clearly shows the loss of the species from eastern England, the only extant populations now being in the Somerset Levels and around the Cheshire Plain. The latter population has been known only since 1990. Perhaps surprisingly, only one species is believed to be extinct, this being Spercheus emarginatus, which was the sole British representative of its family. Considering the species’ apparent preference for highly eutrophic sites, often with abundant duckweed, its disappearance cannot be easily explained. At the other extreme, it is interesting to note that the widespread and abundant Helophorus brevipalpis, perhaps one of our commonest beetles from any family, does appear to be absent from some areas, particularly uplands, but also some chalk and limestone districts.

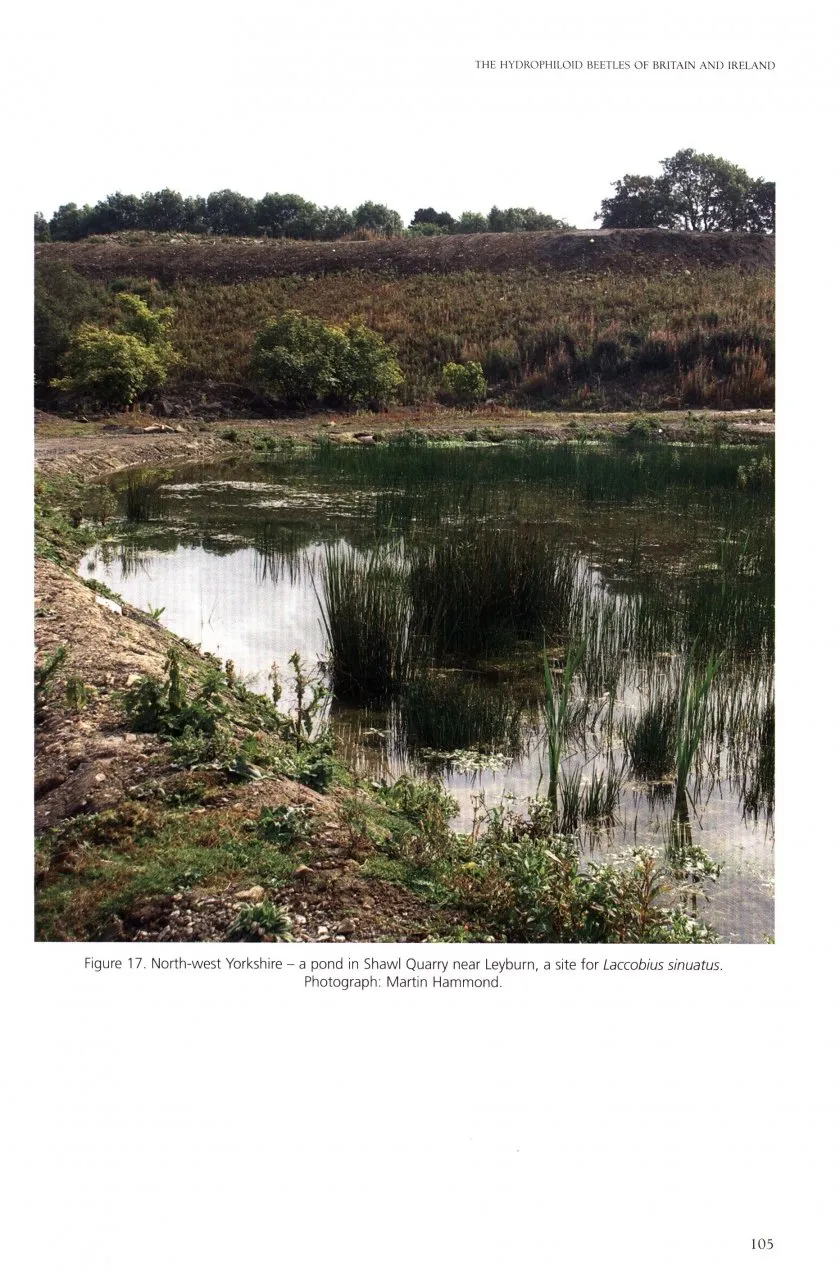

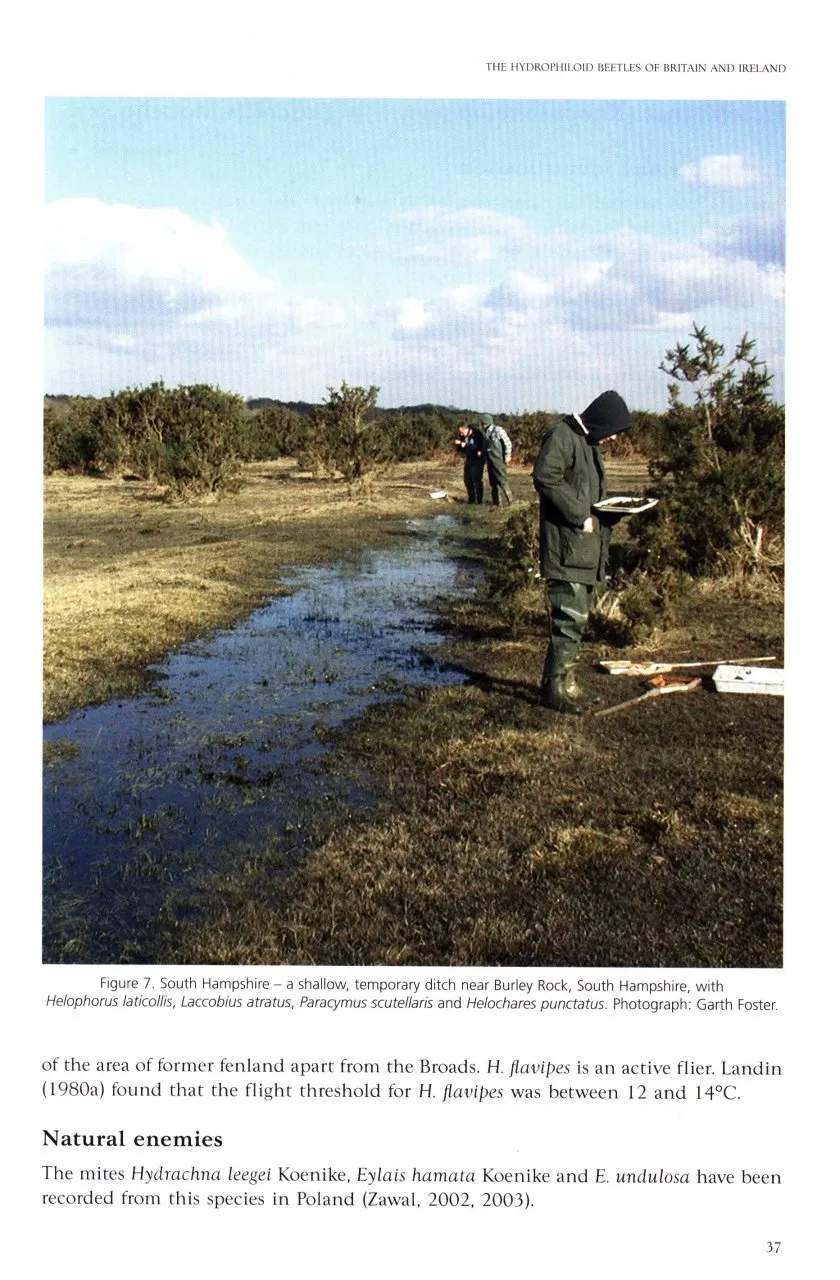

No photographs of the species are included, but anyone with enough of an interest in these beetles will surely also own the RES Handbook, which includes images of all species. What this book does include is a number of photographs of aquatic habitats, with lists of some of the species found there. I was particularly interested to see an image of ‘a drainage ditch on black mud in the Thames marshes’ with a list of six species, including the Great Silver Water Beetle Hydrophilus piceus. This looked almost identical to a pool that I surveyed this year on the Isle of Grain, where I recorded five of these six species, including H. piceus. These photos do indeed give a good idea of the type of waterbody that is likely to support a particular species.

This is the second volume in this series to cover water beetles, the first dealing with the aquatic Adephaga (the diving and whirligig beetles), and anyone with an interest in these insects will surely wish to obtain both books, along with the relevant RES Handbooks for identification. A review of scarce and threatened species can be freely downloaded. Together, these provide as detailed an account as is presently possible for the majority of our water beetles and allied species, and far more information than is easily available for most other groups of beetles. We now eagerly await the final volume, which will cover the remaining water-beetle families, particularly the Hydraenidae and Elmidae.