The name Trevor Beebee has been known to and his writing admired by me for many years. Not only has he forged an eminent academic career but, as I know from colleagues, his advice to those at the sharp end of conservation has been much valued. From his scientific papers I had not realised that he is such a fine writer capable of rendering readable and perceptive prose about even such arcane subjects as computer modelling.

Climate change, with sustainable food production, will be the great environmental challenge of this century. What is not so widely understood is how globally important the data gathered by British naturalist is in understanding climate-change impacts. In no similar-sized part of the world is biodiversity as well recorded over so many generations. This book draws on this important body of evidence and the latest research, with some well-chosen examples from Europe to fill the gaps.

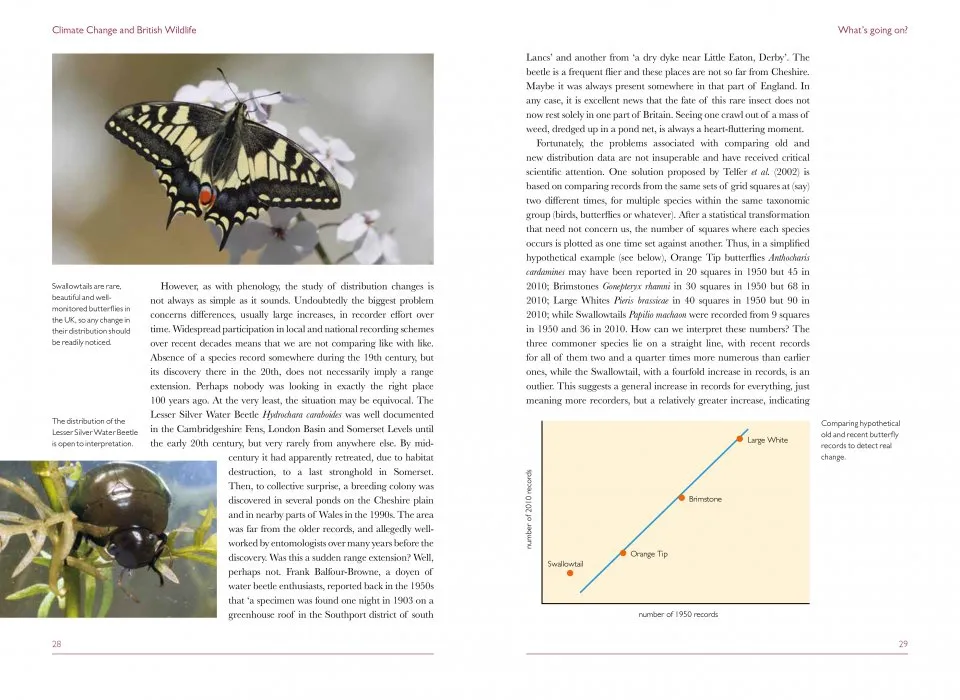

This is not, however, a dry read and it will appeal to the general naturalist as well as the specialist. In the tradition of climate-change science, the first chapter introduces the various types of evidence available about climate change, their value and their limitations. Throughout the book the reader is encouraged not to indulge in over-interpretation of the evidence.

View this book on the NHBS website

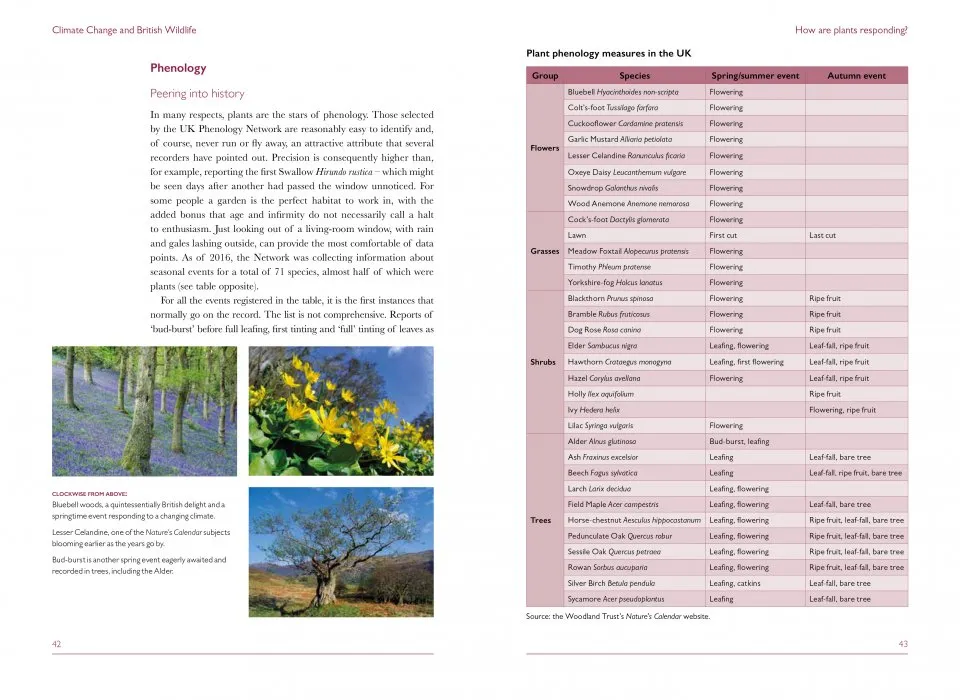

It is often said that lack of information means that most conservation decisions involve flowering plants, butterflies and birds. These three groups and many others are dealt with in separate chapters on plants, invertebrates and vertebrates. For each charismatic group the evidence for phenological change and change in distribution and abundance is reviewed. A convincing case is made for the fact that we have a much richer understanding of invertebrate change through sections on dragonflies and damselflies, the true bugs, bees, wasps and ants, flies, beetles, spiders and molluscs. In the chapter on vertebrates, Beebee begins – perhaps a little naughtily but reflecting a lifetime devoted to freshwater research – with fishes and amphibians, then reptiles, before giving us an overview of the much more extensively researched change in birds and mammals.

Of all the chapters in this book, the one on lichens, fungi and microbes gave me the most pause for thought. Our knowledge of even macro-fungi is notoriously inadequate, and we hardly think of the study of microbes as natural history at all. We often avert our gaze even when it comes to pathogens and parasites. But these are critically important actors on the ecological stage, and by drawing attention to the thinness of our understanding Trevor Beebee lays down a vitally important challenge.

It is, of course, scientifically illiterate to think that we can understand climate change by considering individual species isolated from the community and habitat in which they occur. This is remedied by chapters dealing with freshwater and terrestrial habitats, and coastal and marine environments. Understanding of change at ecosystem level is, in reality, far more complex. It involves a wide set of much less easily interpreted information, confounded by other changes, such as nutrient pollution in fresh waters. Despite this, I think that we get a good sense of the science available and how this can be interpreted. Given the author’s interest, I was surprised that the section on fresh waters is not more extensive. The impact of increased flood and drought on rivers, for example, which is expected to differ markedly between different regions of Britain, is not much examined.

The compilation of information on uplands is especially valuable, while accounts of woodland, heaths and dunes, and farmland complete the picture on land. I was interested to find that heaths and dunes were treated together, this perhaps influenced by the author’s research interest in Natterjack Toads, which, of course, occur in both habitat types. I think that a case is made for the two habitat types having similarities in terms of their response to climate change, with temporary ponds, for example, an important feature of both.

It is true that I am literally allergic to sea water, so I hope that I can be forgiven for a relative ignorance of the marine environment. I found the chapter on coasts and seas informative, but those with a purely marine interest will doubtless be critical, as the earlier, species-based chapters include only examples from terrestrial or freshwater habitats. This is despite the fact that coastal habitats will be most impacted by sea-level rise, and ocean acidification may have an added catastrophic effect.

The inclusion of a chapter on how our own species has responded and will respond to climate change is interesting. It includes discussion of members of the public, scientists, farmers, artists and politicians. I am sure that this subject deserves more research, as we are the ‘ecosystem engineers’ of climate change; how we respond to it will therefore be critical.

When it comes to modelling I am a sceptic, as at times some of the people involved seem to me to have a delusional view of what they are doing. Prediction is treated with healthy realism by Beebee in his penultimate chapter, which includes a timely reminder that experiments are a cornerstone of science. The best experiments, like some mathematical equations, are things of beauty that accelerate our understanding.

The most critical matter of all is how we shall respond to reduce the impacts of climate change. The last chapter deals with this challenge, including the need to reduce the impact of renewable energy and other mitigation and adaptation measures on wildlife.

This is the sixth volume of the British Wildlife Collection and it maintains its established standard of excellence. Based upon its content and style, I think that this is the best environmental book that I have read in a long time.