Peter Marren has already bewailed the current state of England’s National Nature Reserves (NNRs) on these pages (BW 29: 314–319), and I suspect that he is correct to suggest that the situation is just as dire in Scotland. The problem is often one of scale. Small reserves demand fewer resources to manage but are highly vulnerable to outside pressures. It is easier to ensure primacy of nature in larger reserves, but their management requires a huge commitment of time, resources and scientific expertise, and staff probably need to be based on site to ensure genuine custodianship. On that basis, I would question whether any large state-owned reserve in the UK is currently under secure, long-term management.

The Abernethy Reserve in the Scottish Highlands, owned and managed by the RSPB but designated as an NNR, is a breath of fresh air in this context. This book is a magnificent celebration of the reserve, its ecology and the management lessons that have been learnt over the past 30 years. A Swedish forest ecologist once described Abernethy as ‘but a dot’, yet the reserve’s woodland covers around 38km2, including the largest British remnant of semi-natural woodland dominated by Scots Pine. The author defines this as Caledonian pinewood, arguing that the term ‘native pinewood’ has become devalued in forestry usage.

View this book on the NHBS website

The 8,500ha Forest Lodge Estate was bought by the RSPB in 1988 from the Naylor family, who managed it as a shooting estate (more land was added to the reserve subsequently). At the time, it was the largest land purchase ever made by a voluntary organisation in Europe. It included a large hunting lodge which now provides offices and accommodation for RSPB staff. Because staff spend so much time in the reserve, they have an affinity with the land and its wildlife which greatly informs their management of the site. I also wonder whether the arrival of the first Pine Martens on the reserve would have been noted in 1994 were it not for this regular presence.

The size of the reserve is matched by the RSPB’s ambitions for the land. The aim is to return the entire area to as near-natural a state as possible. The author uses a term here that I have not previously encountered: ‘present-natural’, defined as ‘the state which would prevail now if people had not become a significant ecological factor’ (compared with ‘original-natural’, a primeval state that we cannot now observe). I understand the concept but wish that there was a more elegant term for it. To achieve that ambition, staff have been engaged in tree-thinning to establish a more natural structure in former pine plantations and have greatly reduced the Red Deer population in order to restore understorey vegetation.

The book’s author, Ron Summers, is currently a Principle Conservation Scientist at the RSPB. He writes with scientific authority, partly drawing from his own work (he is the lead author of 35 papers cited in the references), but the extent of his background research into topics beyond his own expertise is impressive. Iconic birds like the Capercaillie, Crested Tit, Osprey and three species of crossbill take centre stage, but Summers writes just as authoritatively about plants, fungi, lichens and invertebrates, about the history of the forest and its place in a wider European context. He is remarkably modest about his own work, but I could not help imagining the man hours that must have gone into a 15-year study on the level of cone production and seed fall in the forest, the conclusions of which are boiled down to a single, informative paragraph in the book.

Chapter four is dedicated to the important work, begun in the reserve in 2002 and led by Summers and Mark Hancock, on the role that fire plays in boreal forests as ‘the most important process that disrupts, and thereby shapes and diversifies the woodland structure’. Again, it is difficult to imagine the physical labour that must have gone into the fire experiments the conclusions of which are succinctly summarised in just two pages of text.

Beyond the forest, large parts of the reserve are effectively open savanna. The eventual aim is to extend the forest across these areas into the more mountainous parts of the reserve and re-establish a natural altitudinal treeline. Surveys of pine establishment suggest that it may take 500 years to achieve this, although managed fires may accelerate the process. Broadleaf trees, however, are virtually absent because of past over-grazing, so patches of local provenance broadleaves are being planted to act as a seed source for the surrounding area, a proposal that provoked considerable local controversy, as Summers notes.

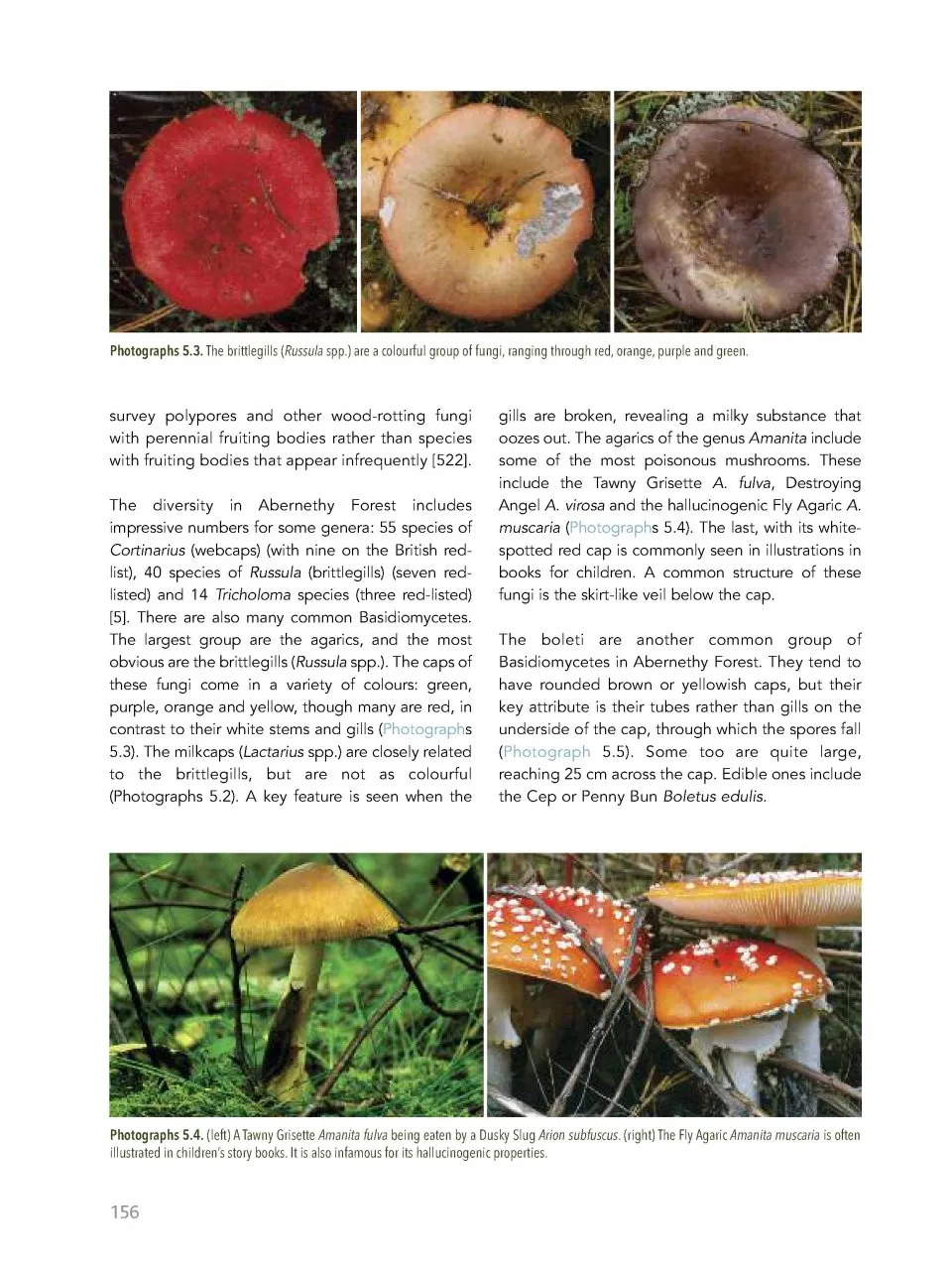

The book is lavishly illustrated with maps, diagrams and photographs, mostly by the author himself. The fungus and lichen photos are especially pleasing. The text is rich in detail, yet remarkably readable. I would have welcomed more insight into some of the main characters who have contributed to the reserve, and a little more personal anecdote to colour the text, like Summers’ evocative account of counting Capercaillie at their leks. I like the simple use of numbers, highlighted in green, to direct the reader to the comprehensive reference list at the end; this greatly aids the flow of the text. Only the index grates; to find out about frogs on the reserve, for example, you need to remember that the species is the Common Frog and search under C.

Anyone with an interest in Abernethy or its component communities should read the book to enhance their appreciation of an inspirational place. Forest ecologists will particularly value Appendix 7, detailing the management methods used on the reserve. Managers of other reserves should read the book as guidance on the level of understanding to which they should aspire in managing their own sites. Resource-starved management staff from the government agencies may simply read it and weep!