For me, this was the most outstanding bird book of 2024. It covers 733 species recorded at least five times in Europe and comprises a hefty two tomes. Volume 1, non -passerines (632pp), weighs 1.8kg, while Volume 2, passerines (424pp), is just 1.3kg. Using photo montages with no background is now becoming the trend for those field guides that want to point out identification details. Each species is shown perched and often in flight with the main identification features marked with pointers. A very succinct text summarises the main features, including moult, age, and gender. If you are looking for information about ecology or distribution, however, you will be disappointed. The lack of any maps is my only criticism.

View this book on the NHBS website

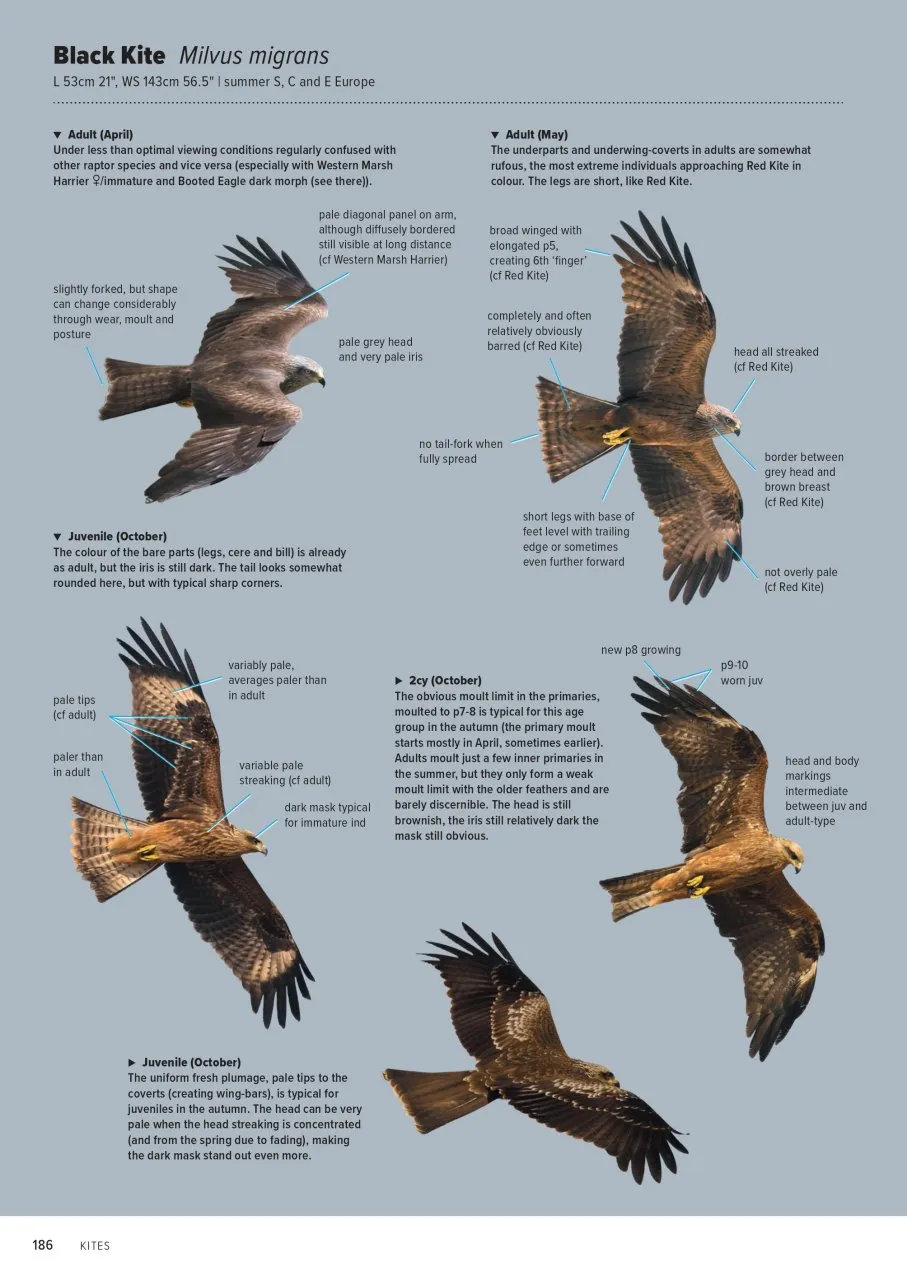

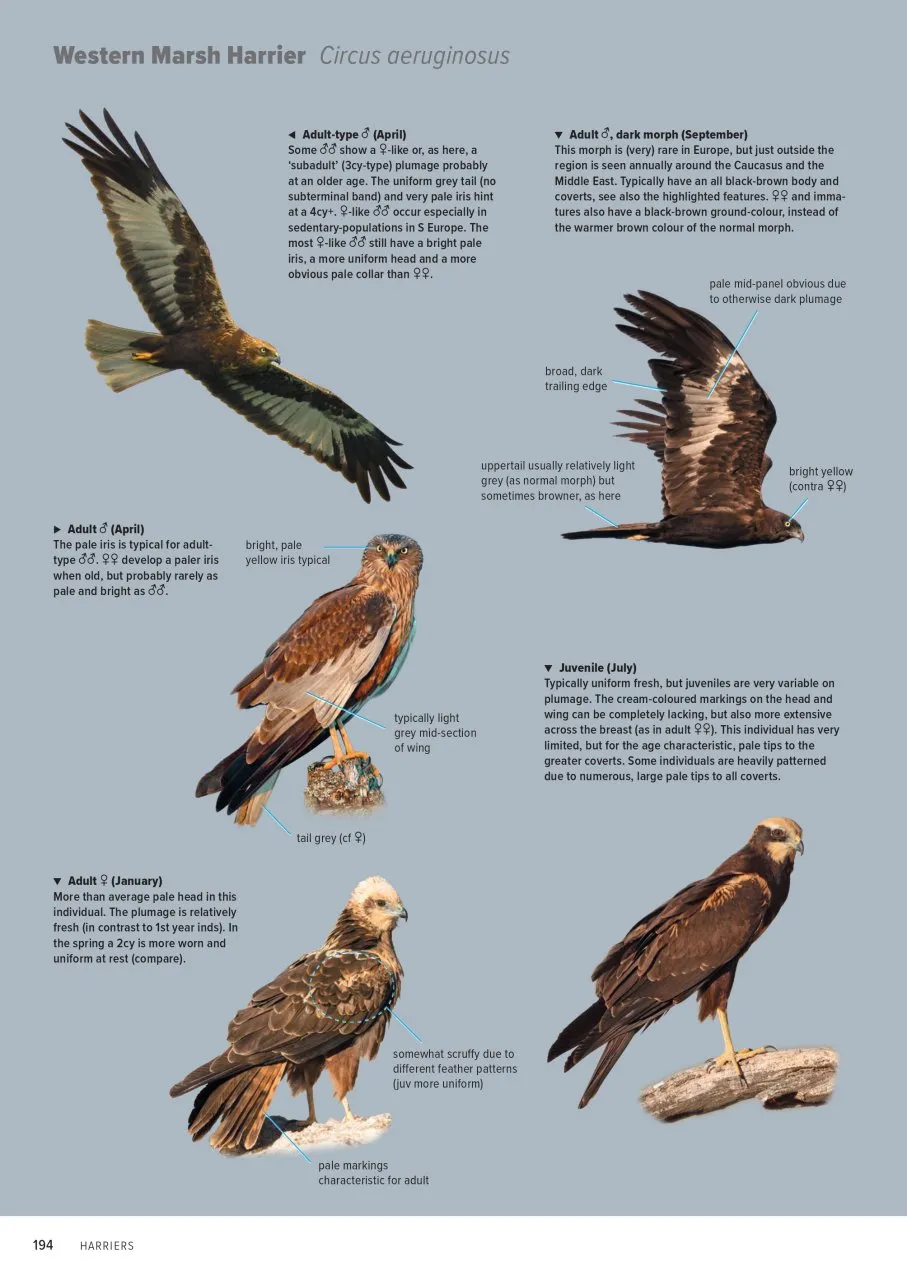

The photos have been digitally manipulated so that each is a cut-out with little (if any) vegetation shown. This takes a while to get used to as it feels rather clinical, but that helps you to focus on the crucial features to look for. Some photographs are of birds in the hand, but edited so that you almost do not notice this. The detail in this book is impressive. For example, I study Red Kites and I have never before seen information on how to tell a second-year bird from a juvenile, but this book explains the differences. Similarly, if you want to spot the differences between a first-year and adult female Hen Harrier, this guide explains the things to look for. The book also allows you to make similar comparisons with Northern Harrier, the North American sister species of our Hen Harrier.

The names used are generally those used by the IOC, with a few tweaks. Each volume has an index, but these are based on the bird’s first name. That is not too bad if you want to find Black Kite, because you can understand that it will be under ‘B’. But what about Penduline Tit? It will not be under ‘T’, so you might assume it must be in the ‘P’ section – but no! It is listed under ‘E’, for Eurasian Penduline Tit. If you want to find the bird that we have always known as Reed Bunting, it is under ‘C’, for Common Reed Bunting. Personally, I like an index where the buntings are under ‘B’ as it allows you to find them faster. This is, however, a small gripe for an outstanding production.

So, who should buy this book? It is aimed at the more experienced birder, but even those who have been watching birds for decades will find ID features of which they were not aware. If you are new to birding, you would probably find Princeton’s two softback photographic guides to Britain’s birds and Europe’s birds more to your liking. Indeed, the latter covers more than 900 species with 4,700 photographs at a fraction of the cost.