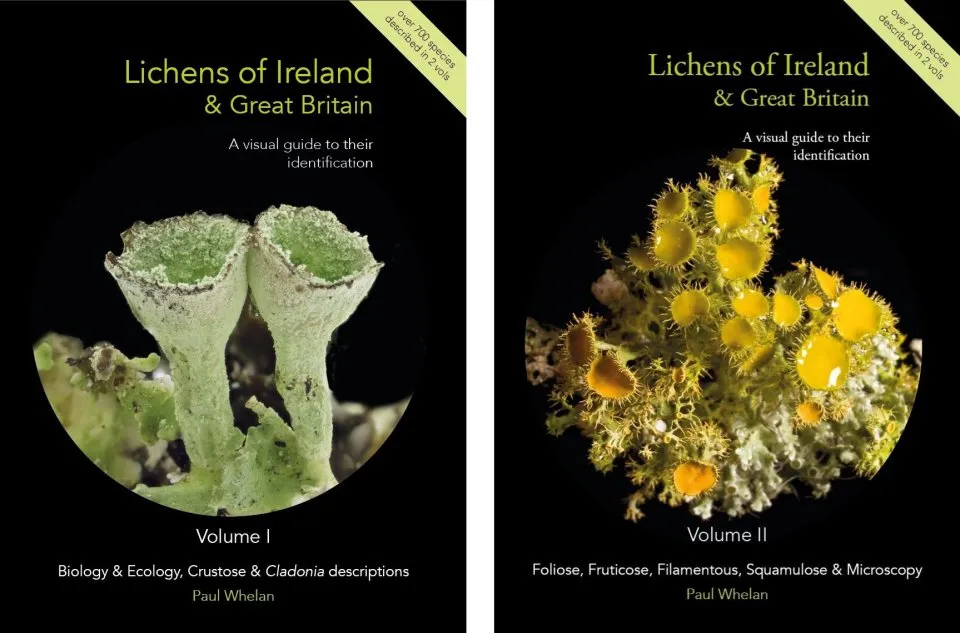

This book contains two volumes, 970 pages, and 6,000 colour photos covering more than 700 species. Spreads available online illustrate the range of topics covered and typical page layouts for the different sections, allowing the scope, high standard and quality of the illustrations to be appreciated. Each species described is accompanied by at least one colour photo, often with additional thumbnail close-up images of significant features to aid identification, and arrows on the main photo to clarify where these features occur. Little symbols are included in the margin of the text to show how one can approach identification of the lichen, such as a hand lens (indicating that ID can be achieved simply by using a hand lens), a microscope, or ‘UV’, indicating UV light. Each of the species described in detail is accompanied by a distribution map. The numerous contributors who provided advice, assistance and shared skills in the production of many aspects of these volumes are generously acknowledged. The British Lichen Society is especially mentioned for sharing data and for promoting lichenology in Ireland.

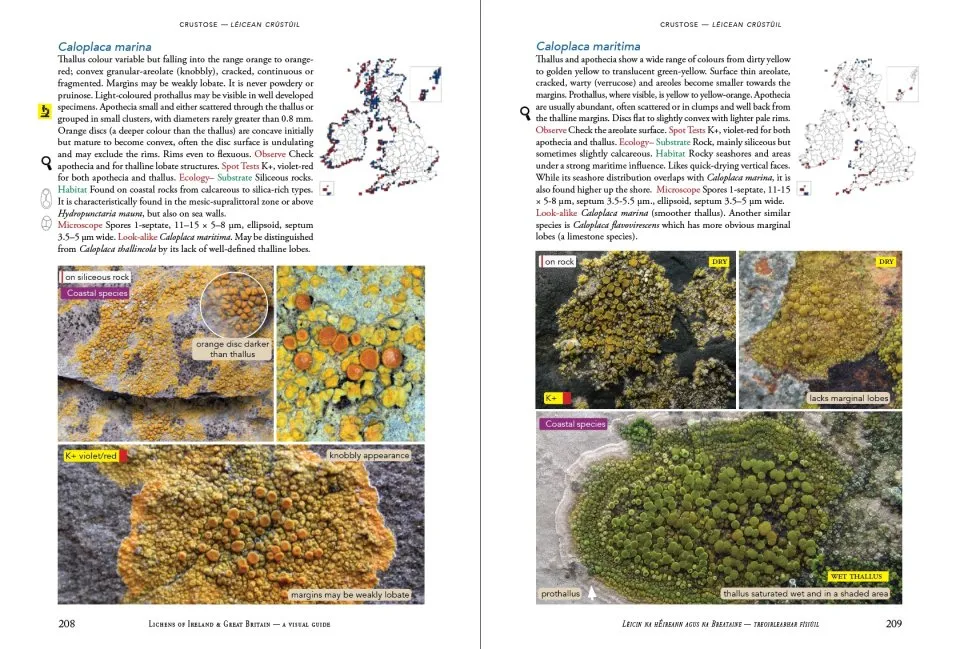

In his preface, Whelan admits that these volumes are a personal view of the lichen world and essentially an educational guide to introduce the public to the rich diversity of lichens found in Ireland. Compared with most introductory lichen-identification guides, Whelan’s approach is unconventional: he has dispensed with using keys and many of the traditional terms used in lichen descriptions, such as ‘shield-shaped’, asking ‘What shape is a shield these days?’ He rightly points out that lichen species invariably display morphological variations – such as the difference in appearance between wet and dry thalli.

He has adopted a novel approach to organising lichen thalli forms based on bauplan, meaning body plan. Originally applied to animals, which are grouped by their different body plans, the author has used this term to distinguish the growth forms of lichens: leprose, crustose, foliose, fruticose, squamulose and cladonia (dimorphic). And it works well; he has taken the division of lichens back to first post – the bauplan. Thereafter, the various bauplans are described and illustrated with photographs and micrographs clarifying features. It is good to find a section on an introduction to lichenicolous fungi, with some useful photos including close-up details.

View this book on the NHBS website

The two volumes are broadly divided between lichen biology and ecology and identification of crustose lichens and Cladonia (volume 1), and identification of foliose, fruticose, filamentous and squamulose lichens, plus lichenicolous fungi, and microscopy and history (volume 2). But there is a whole lot more tucked into these two volumes than lichen identification.

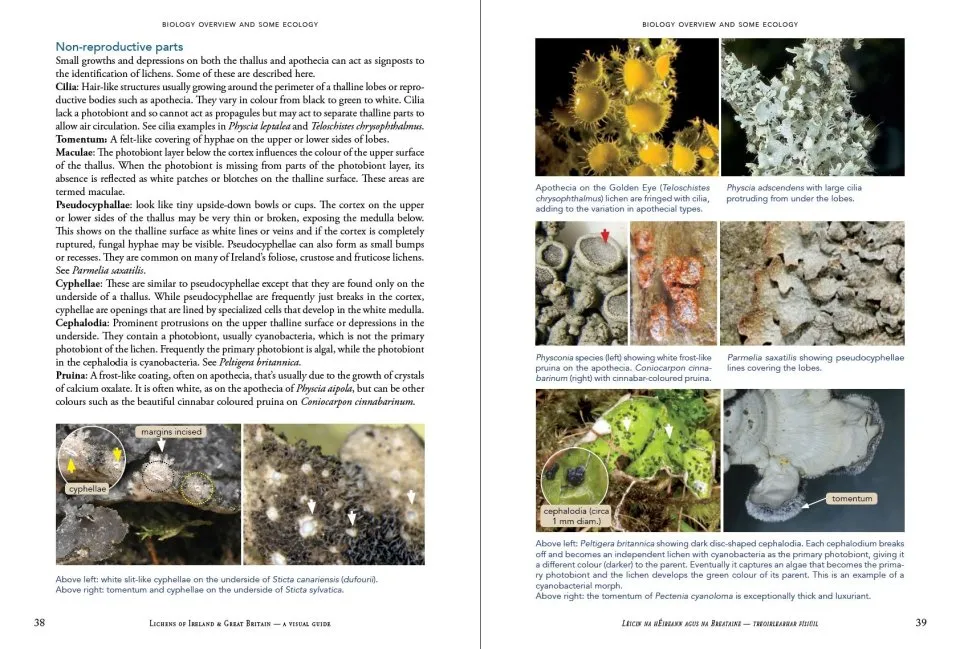

The chapter ‘Biology overview and some ecology’ is generally well done, and in the section ‘Lichen’s kinship place in nature’ he tackles modern concepts of species, genera, families, and how DNA has revealed connections that were not so evident when relying on observing morphology and anatomical structures. I found this and the following chapters very readable and, although concise, the text has a clarity that enables a path through the complex relationships to understand where lichens sit in the scheme of things.

This guide is boldly titled Lichens of Ireland and Great Britain and Irish names are discretely woven into the volumes throughout, along with an appendix on lichens in the Irish language. The Burren limestone, Atlantic hazelwoods and the Killarney woodlands are cited as particularly important Irish habitats for lichens. Of course, though, these volumes have a wider scope applicable to Britain and northern Europe. In volume 2, I enjoyed the history and biographies of lichenology, including outline histories of lichenology in Ireland and biographies of important Irish lichenologists. This section was completed by inclusion of artistic illustrations of lichens. Several poems are scattered throughout both volumes, including one by Clare Goulet, a poet based in Nova Scotia, whose poem ‘Verrucaria maura – Sea Tar’ is particularly relevant to Ireland from its reference to Matilda Knowles. Weighing about 2kg, I am not sure one would want to carry these two volumes into the field, so identification needs to start with looking at specimens collected in the field. There is a guide to essential equipment for studying lichens in the section on biology and ecology.

Ongoing name changes are a source of frustration and there is no way a printed publication can ever keep up to date. Throughout the book, Whelan has therefore directed the reader to consult with the British Lichen Society’s online Taxon Dictionary, where current names are shown together with synonyms. He has, helpfully, also added a separate index of synonyms of older names that the general reader may be familiar with from previous publications.

The only section I am not entirely comfortable with is Whelan’s ‘Partial Binomial Naming System – a Suggested Educational Naming System’. Although I can see the reasoning behind including this – that a stumbling block for beginners is learning scientific binomial names, further exacerbated by ongoing changes from taxonomic revision – I wonder if this is simply going to add to the confusion.

There is so much contained within these two volumes – a compendium of lichens and lichenology – that it is difficult to know what to leave in or leave out of this review. The emphasis is on identification, but so many other sections provide useful backup, helpful information and tips.

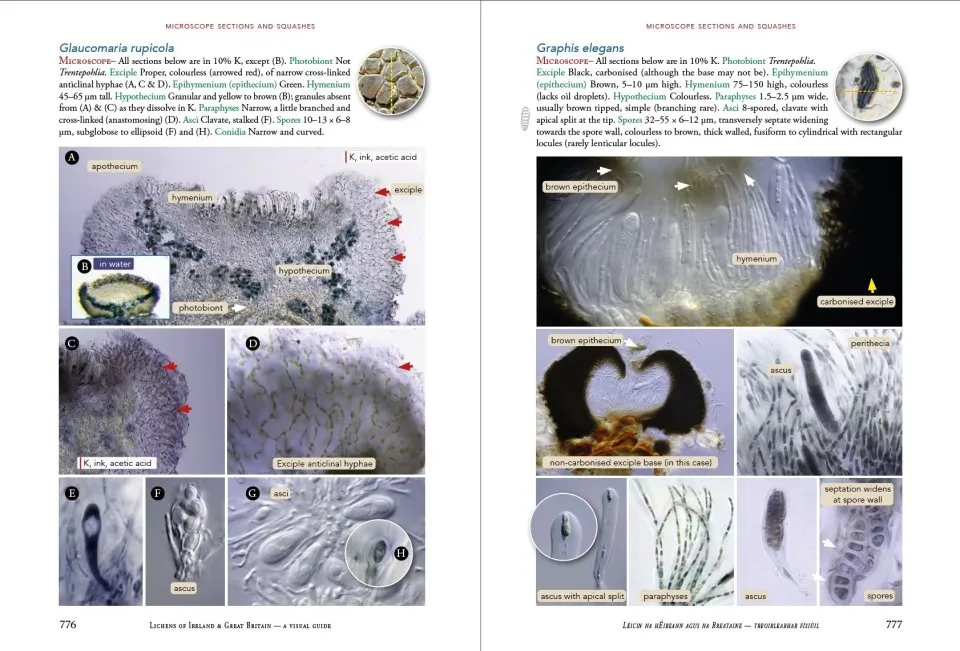

When I began to look at lichens, way back in the early 1970s before the advent of online searching, I used the Observer’s Book of Lichens, and then graduated onto Duncan’s Introduction to British Lichens. And then came ‘Dobson’. Today, there are so many more lichen identification guides, both published and online. The thing I realised, however, was that relying on only one source was not always satisfying. Once I had found the name of a species I was looking to identify, I always went to check with another book. And if the answer was the same, then good. If not, well, go back and try again! And that practice still holds good; lichens can exhibit wide morphological variations and this can frustrate identification attempts, no matter how well written the identification guides are. Whelan emphasises that one of the aims of his work is to encourage amateurs to use the compound microscope, and to that end he has a pretty comprehensive section on microscopy. And, taken logically, as Whelan says, lichenologists are a friendly lot, so meeting up with others to share experiences is rewarding, either by joining the British Lichen Society (which does hold meetings in Ireland) for meetings led by experts or joining local groups.

So, do these two lavishly illustrated volumes contribute significantly to the stable of lichen identification guides? I would say emphatically, ‘Yes’. These works are produced to a high standard and are truly inspirational, and a delight to possess. They will enthuse and encourage. There is a tremendous excitement about discovering lichens, and the delight in settling down, poring over your specimen and searching for a name through available publications has just been enriched with these volumes.