In recent years, wildlife gardening books have sprouted like asparagus spears, urging us to dig a pond, plant a wildflower meadow or build a log-pile. Concessions to wildlife have become prevalent enough for television presenter Alan Titchmarsh to protest earlier this year that the activity should not replace ‘traditional’ gardening. What he would make of Paul Sterry’s The Biodiversity Gardener, I can only guess, but is that the grinding of molars I hear above the buzz of the hedge trimmer?

This book is nothing less than a call to arms which puts wildlife firmly at centre stage. It is an impressively thorough and highly readable account of how Sterry has devoted his half-acre plot in Hampshire to native biodiversity. From the outset he makes it plain that the book is not about ‘conventional gardening’, but is a serious attempt to redress the almost universal decline in wildlife and habitats in the UK. He has little faith in much of the current generation of politicians, the farming community or ‘aspirational landowners’ to make the necessary improvements, and so he urges his readers to follow his example and manage the land they own or control for wildlife in the hope that, should the tide of loss turn, these islands of native biodiversity will act as life rafts.

View this book on the NHBS website

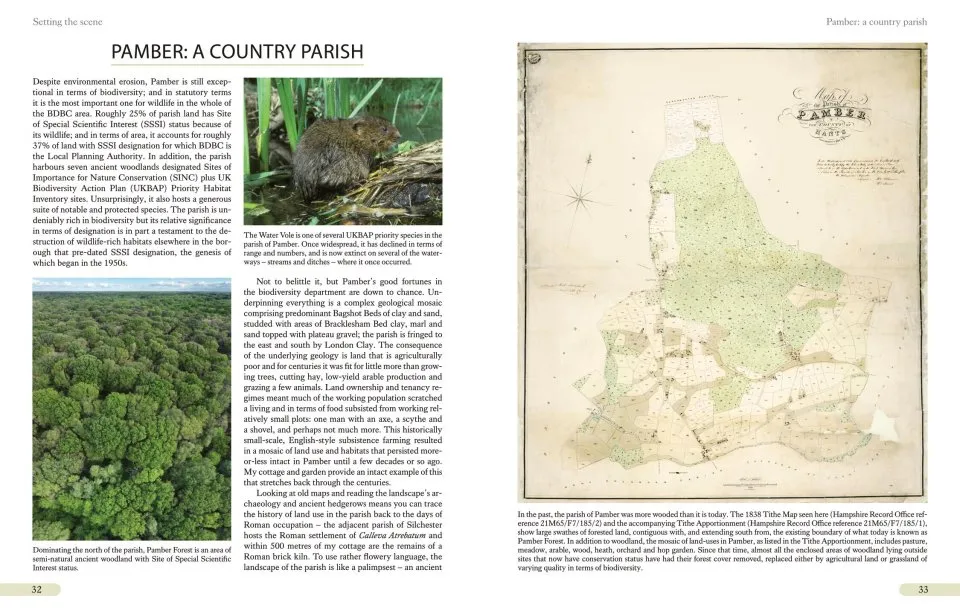

The text is woven throughout with a lifetime’s knowledge and dedication. Following the introduction, which explains the urgency to conserve, illustrated in part by a scene-setting history and natural history of Pamber, his home parish near Basingstoke, Sterry introduces us to key elements on which we might found a biodiversity garden: the all-important soil, the grassland, woodland and freshwater. These chapters cover habitat creation, management and ecology, but he does not always tread familiar paths, taking us instead down byways which a blander gardening guide would shun. I found myself grinning in sympathy at his peroration on the annual seeding of wildflowers at road verges, accompanied by a photo of a ‘ghastly mix’ of cornflowers, poppies etc which are ‘essentially worthless’ to native wildlife. Ragwort is staunchly defended, but, as ever in this book, Sterry backs up his arguments with appropriate references. Later he celebrates Ivy and pans Buddleia, for which he has a ‘morbid dislike’ though he tolerates a single bush in his garden.

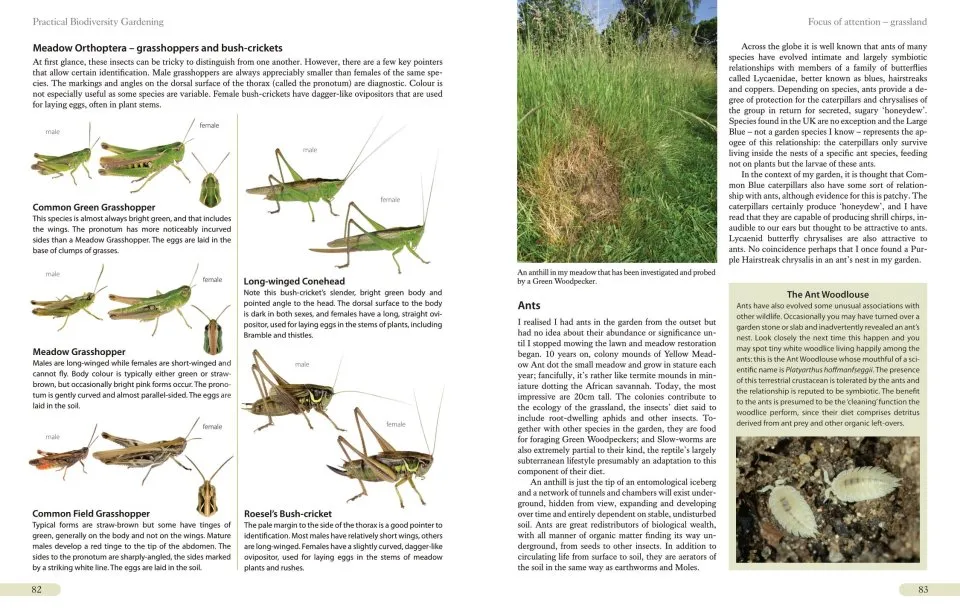

Foundations laid, we are ready to meet the wildlife. As you would expect from such a prolific author and photographer, these accounts of plants, fungi, invertebrates, reptiles and amphibians, birds and mammals are detailed, accurate and copiously illustrated by photographs, mostly his own and from his garden. Refreshingly, invertebrates are awarded a whopping 91 pages, including an in-depth section on butterfly life-cycles (Purple Emperors and White Admirals are among his garden visitors) and a glorious array of moths and advice on how to record them. Observation and monitoring of the fruits of biodiversity gardening are fundamental to understanding their ecology, and Sterry urges us to record our findings through local and national schemes as well as for our own pleasure. I particularly liked his compendium of trail-camera images and signs of mammal activity, including nibbled nuts, skulls and owl pellets. He crams in a significant proportion of the garden wildlife which you can expect, although readers outside southern England will naturally experience a different selection. This is not a comprehensive field guide, but there are valuable links throughout to organisations and websites which offer more information.

I thoroughly enjoyed this well-designed, informative and utterly different wildlife gardening book and as a keen observer of my own (much humbler) garden I can wholeheartedly recommend it. There really is something here for everyone: even hardened naturalists, such as British Wildlife readers (this journal is referenced several times), will find new and useful information. It is often challenging, even controversial in places, but contains vital food for thought on many aspects of our attitudes to contemporary conservation, inside and beyond the garden. If I have a reservation, it is that biodiversity in this context means native biodiversity, and I wonder if that is too idealistic an approach, given that our gardens are key arrival points for many new and seemingly unstoppable species, and that non-native horticultural favourites can also be valuable nectar sources for native insects. Sterry’s point, of course, is that in the face of introductions and aliens, it is imperative to support native wildlife however we can if we are to create a legacy for the natural world. I hope sincerely that enough people take his advice.