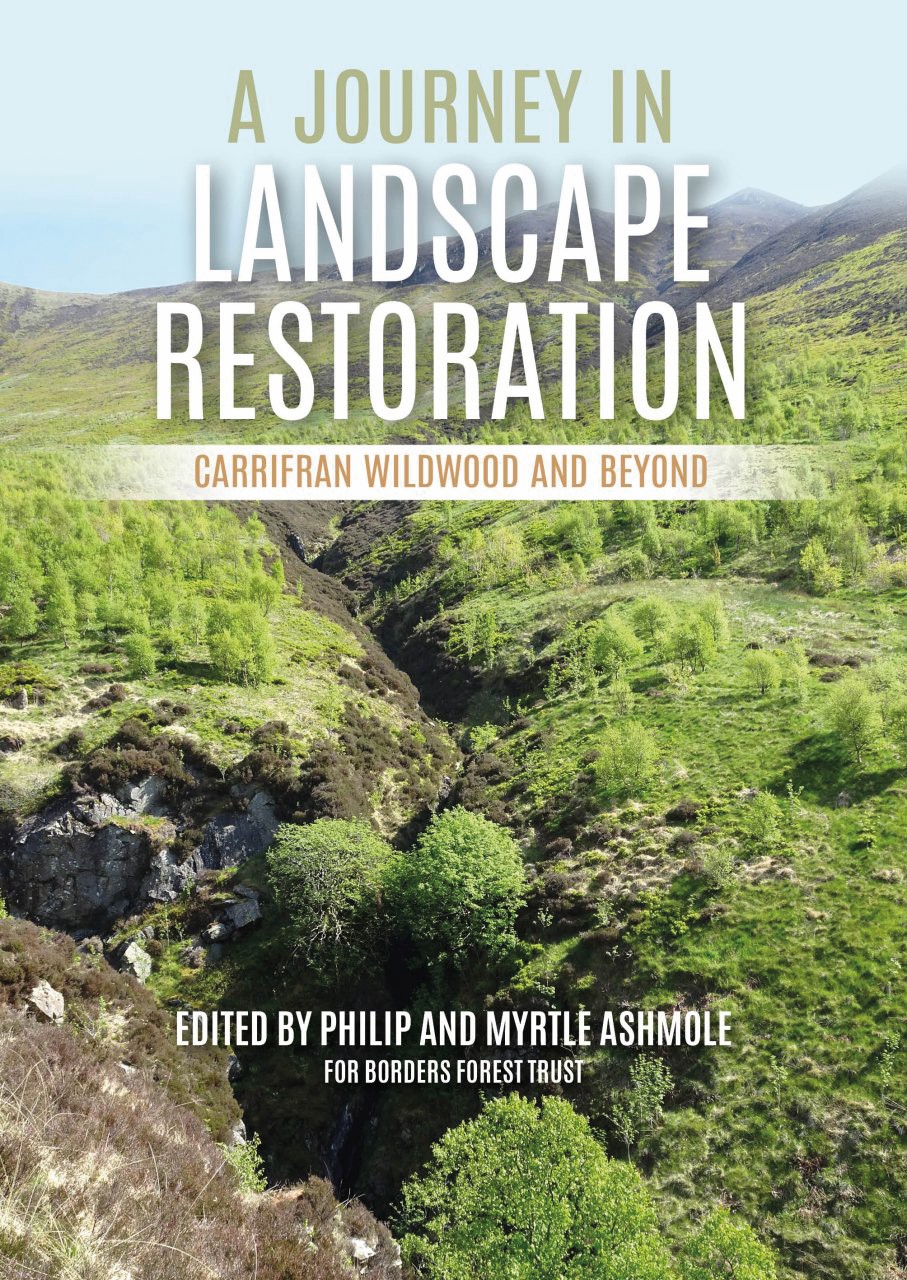

Two decades ago nature was returning to an English farm, providing the source material for Isabella Tree’s inspirational bestseller, Wilding. At the same time trees were being planted to restore a 640ha slice of the Moffat Hills. So began the journey in landscape restoration described in this new book. It is ‘the inspirational story of how a group of motivated people can revive nature at a landscape scale.’

Carrifran Wildwood adopted a mission statement ‘to re-create, in the Southern Uplands of Scotland, an extensive tract of mainly forested wilderness’. Heavily sheep grazed, largely denuded hills rising from 200m to well over 600m near Moffat demanded a proactive approach to tree planting, unlike that adopted at Knepp Castle. The transformation that has taken place, how it has been achieved and how far its ripples have spread, is the subject of this book. The task of knitting together almost fifty disparate voices into one volume may have been as nothing compared to that of buying and restoring a large piece of difficult terrain, with many interests, individuals and agencies to please.

View this book on the NHBS website

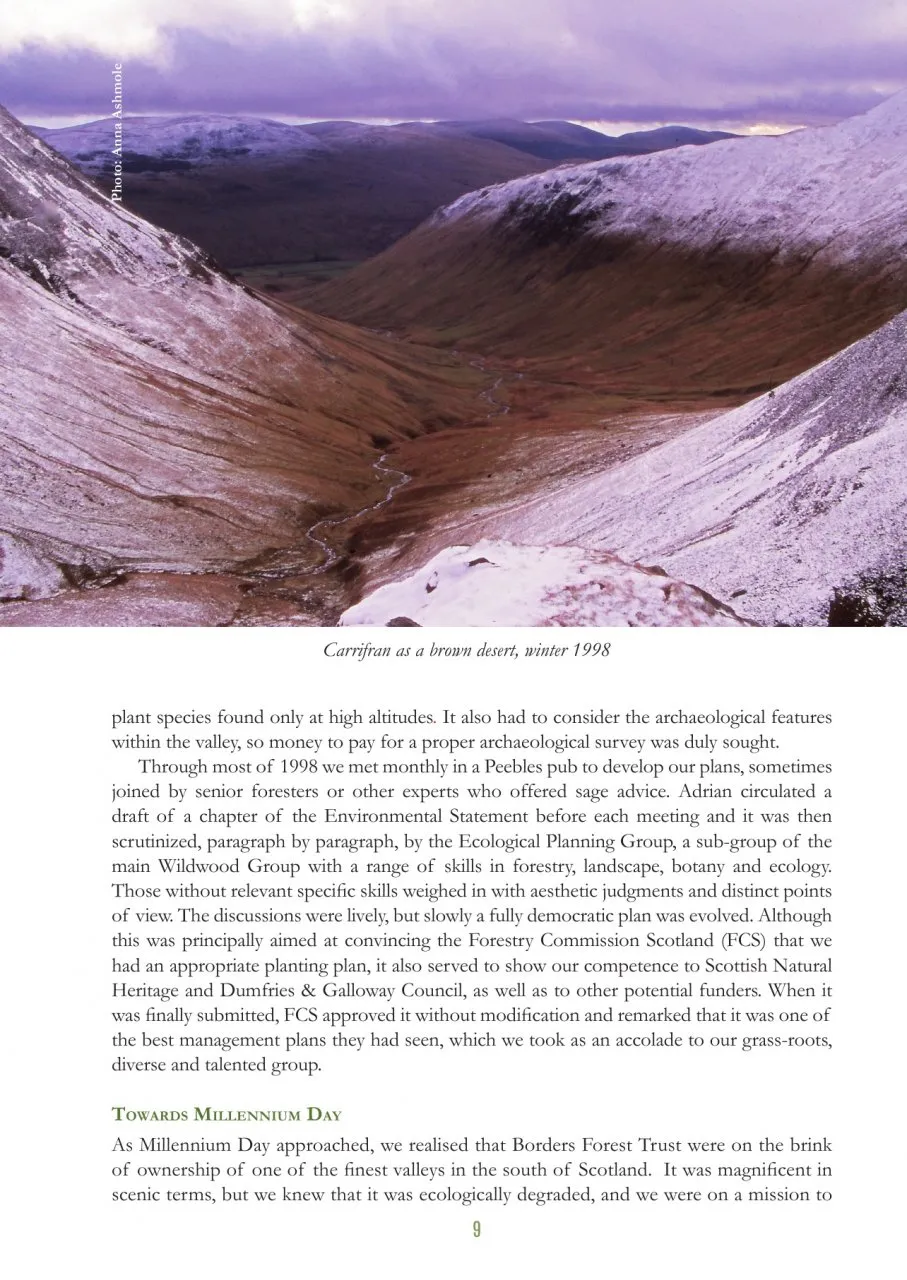

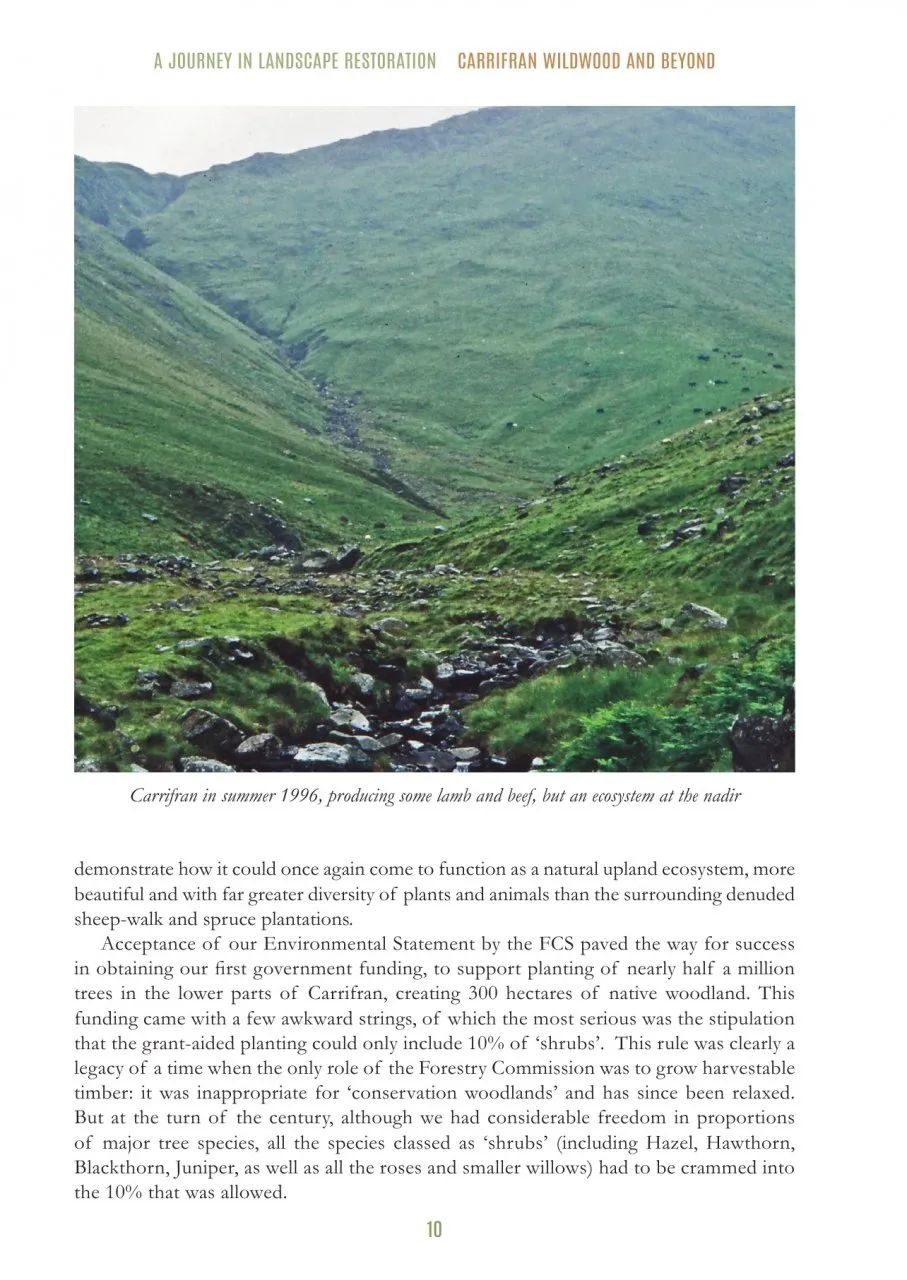

The book is structured into three unequal parts. Each consists of a number of short sections. Additional text in boxes and copious illustrations together form nearly half the book. Part one, ‘Making a dream come true’, has only two sections. These deal with the project’s beginnings and the struggle to bring back trees. To do so the decision was made to take the ‘King’s Shilling’, eventually amounting to £400,000 of Forestry Commission grant money. This brought with it the hugely demanding target of planting 60,000 trees each year for five years. It also brought limitations; one of these was that grant-aided planting could only include 10% of ‘shrubs’ such as Hazel, Hawthorn, Blackthorn, Juniper, all the roses and smaller willow; these are among the most appropriate species for restoration planting.

The struggle to establish young trees is full of dilemmas, such as whether to use herbicides (no longer used) and how to protect young trees, particularly from voles, which turn out to be the greatest threat. Young trees are grown in cells with added fertiliser, which makes them particularly attractive to passing herbivores. Tree guards of various kinds have been tried, with varying degrees of success, distorting young Juniper; but it turns out that voles do not like Juniper, so they can be planted without guards of any kind. The Carrifran approach to tree establishment has moved away from blanket protection to as little as possible. Practical experience such as this provides a trove of lessons learned and pitfalls to avoid.

Part two, ‘Seeing what nature can do’, records the positive changes to flora and fauna which have been observed over the life of the project, including an overview of the complexity of the Mycota by Roy Watling. The decrease in fruitbodies of larger fungi is put down to the rank understorey of grasses and tall herbs resulting from the exclusion of sheep and goats with fences, and shooting of about 20 Roe Deer annually to suppress their effect on young trees. The management is summed up in the title of the conclusion to this part, ‘Nature still needs a hand at Carrifran’.

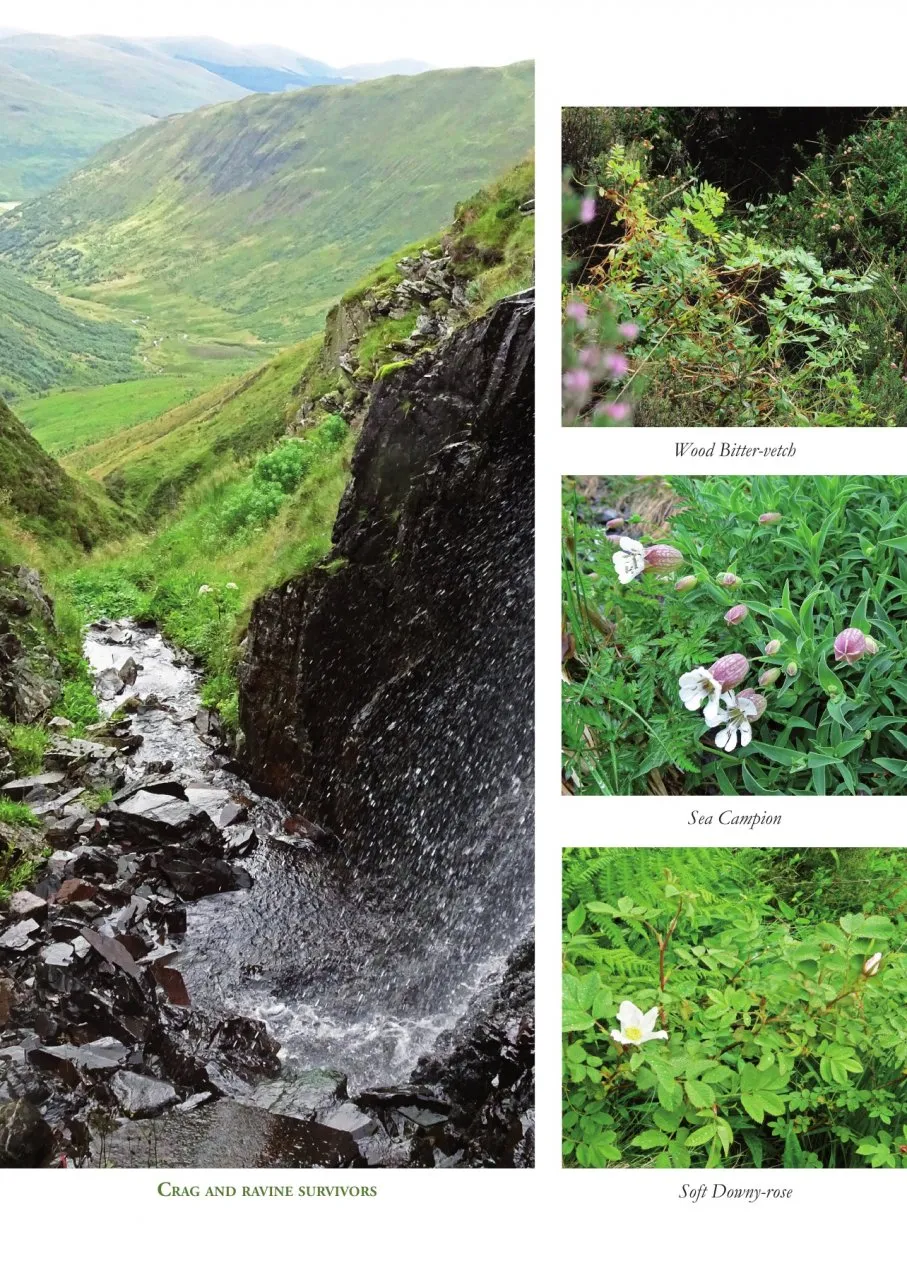

This interventionist approach is not limited to trees and shrubs, but includes planting climbers like Ivy and Honeysuckle, montane scrub species, and translocations of Bearberry and Oblong Woodsia. Other species in the project’s sights include Wood Bitter-vetch, Petty Whin and Dwarf Cornel, and a number of species never recorded at Carrifran, such as Black Alpine Sedge, Alpine Mouse-ear, Alpine Saxifrage, Purple Saxifrage and Pyramidal Bugle. To break up the thatch and open up the sward the intention is to introduce pigs. Introducing domestic cattle, we are told, ‘would reduce the feeling of wildness in the valley’.

Part three, ‘Reviving the wild heart of Southern Scotland’, widens the focus. In 2009 Borders Forest Trust (BFT), the body behind the Carrifran experiment, purchased the 640ha Corehead Farm, which included the popular landscape feature of Devil’s Beef Tub, for £700,000. While retaining 300 Blackface ewes and followers, 230,000 trees are being planted over nearly a third of the land. Removing all the plastic tubes will be a major task. Then, in 2013, BFT acquired the 1,832ha Talla and Gamesthorpe adjacent to Carrifran. This more than doubled BFT’s land holdings.

Beyond this core, Carrifran has been a catalyst for other ecological restoration projects, such as the Kielderhead Wildwood project, which has planted 100ha of heather moorland with native tree species. Although most of the book equates restoration with tree planting, some attention is given to repairing peatland. One section discusses the ‘conservation prison’ of designations – Carrifran forms a fifth of the Moffat Hills SSSI. Yet there is no mention of the fact that without notification the land would have been afforested, as has the adjacent 300ha Polmoodie Forest which occupies the southern and eastern flanks of Carrifran Gans. Huge stretches of the Southern Uplands are now cloaked in conifers, at great cost to peatland and upland habitats and water quality. The dominant position of the Forestry Commission would be reason enough to avoid this ‘elephant in the room’.

Many hours must have been spent debating the way forward and working through the tensions arising from different viewpoints. They are not on show here. In commissioning the book, BFT wanted to share its vision of a wilder future for Carrifran and beyond, in which landscape restoration takes full account of the interests of communities and nature, and some treading on eggshells was inevitable. Niggles include the surprising decision to use hardly any scientific names for animals or plants and not to include any in the index. The bumpy format, which is most readily dipped into rather than wolfed down, is veined with a strong community and volunteering ethic, and set against the backcloth of land reform in Scotland. It should appeal to readers thrilled by BFT’s ambition and hoping to follow in its footsteps. The editors have made available a rich resource of information and illustration about a topical issue at a critical time. If the aim of the book is to make the reader want to visit Carrifran and its sister properties, it has worked on me.