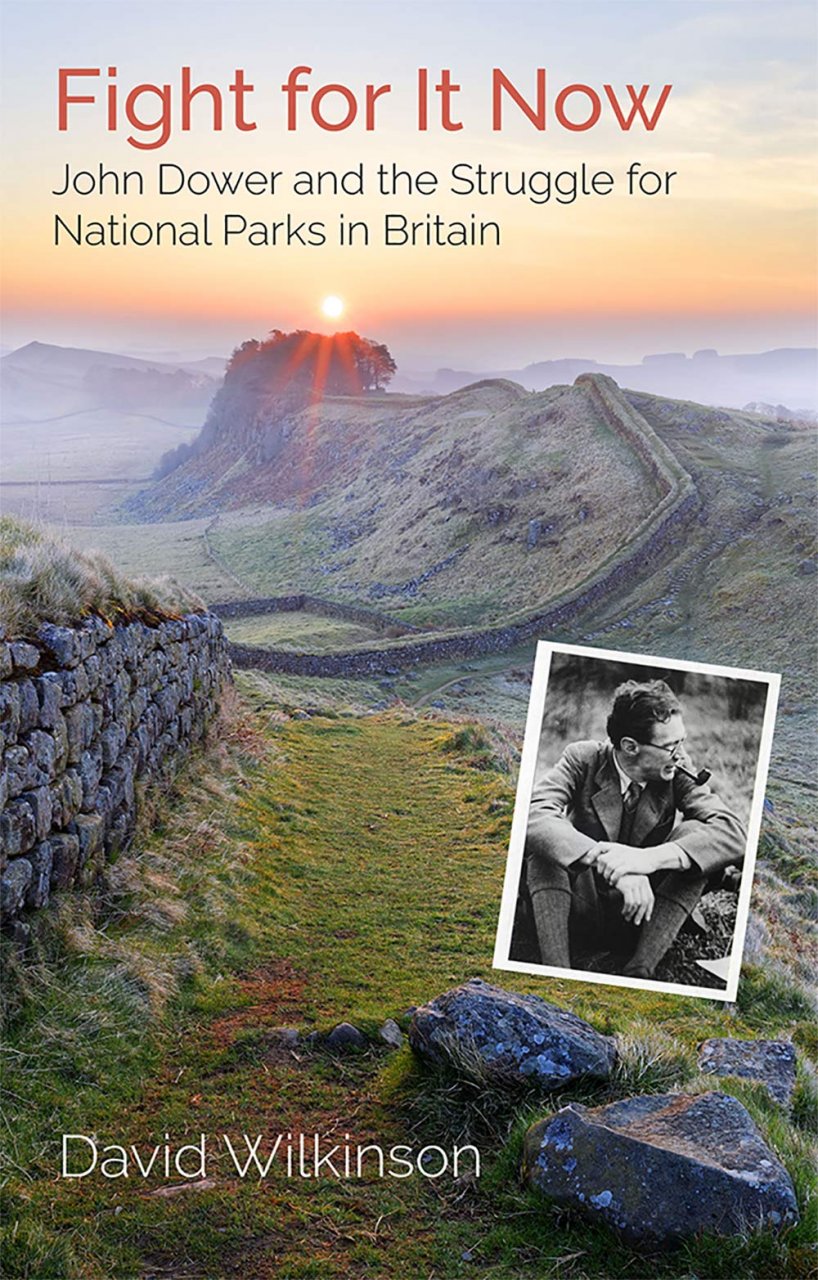

John Gordon Dower is almost forgotten today. He should be one of the great heroes of landscape conservation because he, more than anybody, was the founder of our National Parks. It was Dower who formulated what the Parks were for, where they should be located, and how they should be run, and who drafted the key report National Parks in England and Wales, his ‘one-man White Paper’. Yet until now there has never been a biography of Dower, and one wonders why not. One reason may be that he tended to work quietly behind the scenes, and even in this account he sometimes becomes almost invisible. He was neither a politician nor even a senior civil servant (he rose to Assistant Secretary in the Ministry of Town and Country Planning). Even his greatest achievement was posthumous, for Dower died of TB two years before the landmark 1949 National Parks Act.

Nonetheless there was clearly something about him. His enthusiasms – hill-walking, nature, good architecture – were catching, and his prose style was clear, forceful and direct. Again and again in David Wilkinson’s detailed and sympathetic biography, you sense Dower’s determination and perseverance, driving forward his vision of the National Parks that would preserve the best of our rural landscapes (and their wildlife) while rewarding the war-weary British people with the freedom to wander (and Dower meant wander: he had no time for waymarks). The drama of the story lies in the obstacles that he and his colleagues needed to overcome in their David-and-Goliath battles with the land-owning ministries and the Forestry Commission. Fortunately, they had public opinion on their side. They were the progressives.

David Wilkinson’s previous book, on the final years of Kenneth Allsop, charted a ready-made tragedy. John Dower is more difficult to bring to life. Tall and wiry, with tortoiseshell specs on a thin face, often with a pipe clamped between his jaws, he seems at first an unlikely hero. He loved the outdoors and was a great walker (and a keen huntsman). He deplored ugly developments of the kind that had blighted our coastline. He wanted to preserve Britain’s beauty and make it more accessible. He had some advantages. He married into the Trevelyan family, which gave him an influential ally in the liberal statesman Charles Trevelyan, and the lifelong support of his wife, Pauline. His later career in Whitehall was assisted by Lord Reith, then Minister of Works. Wilkinson uses contemporary documents and letters to present a blow-by-blow account of the tortuous process that led to the Hobhouse Committee and the Parks. In the later stages the story becomes oddly gripping and even rather moving. The book has too many clichés: ‘a tall order’, ‘jewel in the crown’, ‘pull no punches’. The approach is microscopic rather than telescopic. All the same, this is a story that needed telling, and is a welcome reminder that, even in the civil service, a strongly motivated individual can sometimes create something lasting and a force for the good. David Wilkinson has done justice to a forgotten hero.