An account of the larvae of British beetle families has been long awaited and eagerly expected. In many cases, the larvae are much longer-lived than the adults and are therefore more easily found. Apart from the six people named as authors, numerous others are acknowledged for their contributions ‘over its more than 40 year pupation’. The result is certainly a remarkable achievement, since the larvae of many, perhaps most, species of beetle have never been adequately described. It must be said that study of beetle larvae is far behind that of the adults and requires a good deal of patience and dedication. As with all insects which undergo complete metamorphosis, the larval structure is very different from that of the adults. Even those of us well accustomed to the terminology used for the identification of adult insects will find numerous unfamiliar terms in the seven-page glossary, a whole new vocabulary to be learned.

After several introductory sections, including a key to aid the separation of beetle larvae from those of other orders, there follows a very comprehensive key to families and some subfamilies. This key alone runs to 70 pages. Inevitably, the characters used require careful microscopic examination of properly prepared specimens, the details of the mouthparts being particularly important in many cases.

View this book on the NHBS website

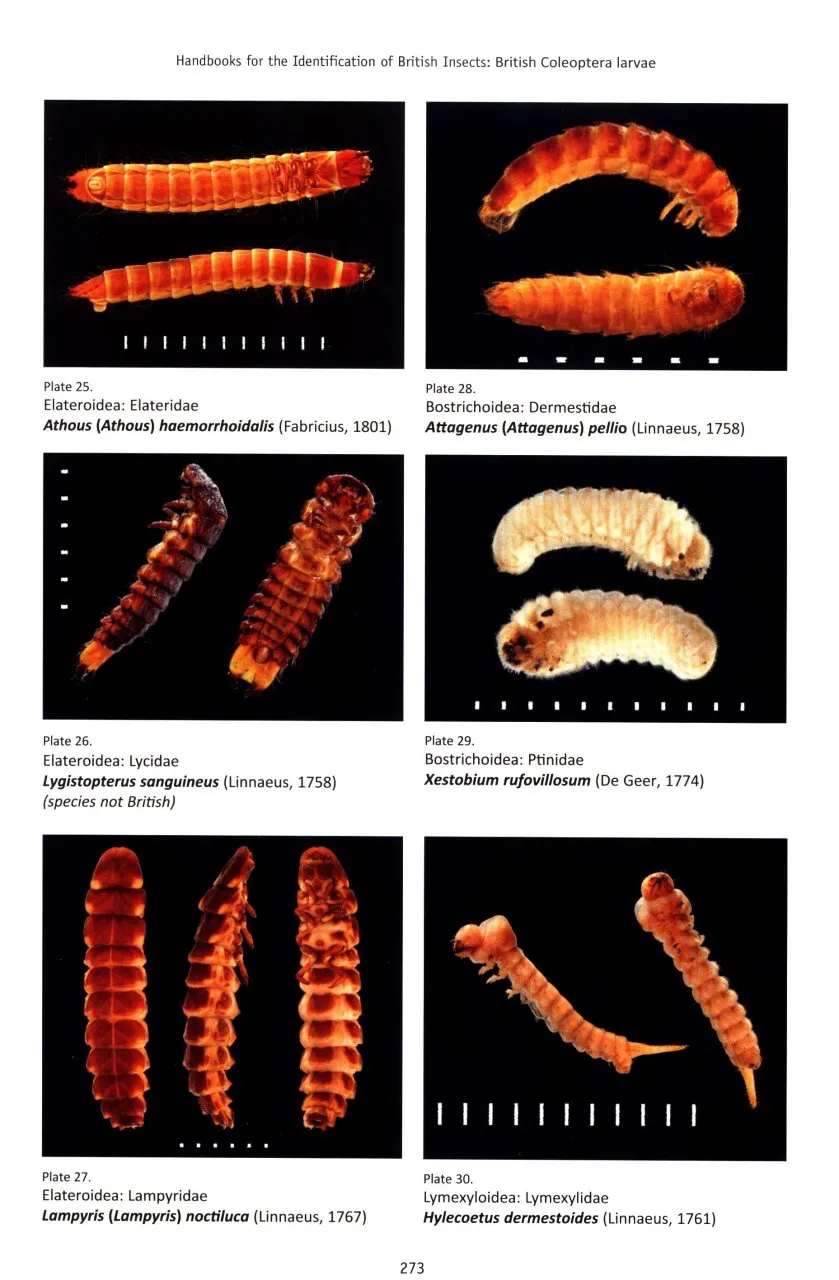

Accounts of the species and major subfamilies form the largest part of the book. These include details of larval habitats and feeding habits where known, as well as illustrations of both whole larvae and characters used for identification. The work is completed by 68 colour plates of larvae, almost all of preserved specimens. As there are presently 113 beetle families recorded in Britain, and more than one example is shown for some of these, many families clearly are not represented at all in these plates. There is also some inconsistency in the location of the figures, particularly of whole insects. On the one hand, an identical illustration of the longhorn beetle Hylotrupes bajulus has been reproduced three times: first in the key and then in the accounts of both the family and the subfamily, the last two appearing on successive pages. On the other hand, I wanted to find whole-insect illustrations for the water beetle families Hydraenidae and Hydrochidae, neither of which is shown in the colour plates. There appears to be no whole-insect illustration for Hydrochidae. I did eventually find an example for Hydraenidae in the key but, unlike many of the other families, this was not copied to the family account, which makes it more difficult to locate. Unfortunately, there also appears to be an error as identical figures are shown under Hydrochidae Hydrochus angustatus (Fig. 203), where they are apparently correctly, and again in the account for Hydraenidae (Fig. 208), where they are labelled Hydrophilidae. One assumes that this is an error which should have been picked up in the proofreading stage and, while it is the only one which I have noted so far, it was noticed only by chance, and critical reading of the whole work may therefore reveal others. I suspect that an errata sheet may be necessary, although one was not included with my copy.

With the exception of a few groups, such as ladybirds, the identification of beetle larvae beyond the family or subfamily level is likely to remain extremely difficult for some time to come. The scattered nature of the existing literature is demonstrated by the fact that the references take up 30 pages, and many of the ones that are included are likely to be available only to those with access to a major entomological library. For most people, the only way to identify a larva is by rearing it through to the adult stage, a process which is quite straightforward for some species but very tricky for others. In the introductory section dealing with the preservation of specimens, the subject of DNA techniques is given some prominence. While this is hardly practical for most of us, it would seem likely that DNA analysis will prove particularly useful in the future for associating larvae with adults without the need to rear them.

This has proved to be quite a tricky publication to review. On the one hand, it is a remarkable work that has involved many individuals, some of whom are no longer alive, and a great deal of specialist input. Any serious coleopterist will want it on his or her bookshelf. Whether it will inspire people to undertake further larval studies is another matter, as the subject is likely to appear so complex as to be beyond any but a few specialists. For the more general naturalist or entomologist, the appeal is likely to be more limited. Certainly, there is little possibility of finding a random beetle larva and identifying it even to family level by comparison with the plates and drawings. This is not a criticism of the book, but rather a consequence of the intrinsic difficulty of the subject. There is an opportunity for someone to produce a different work, perhaps online, showing examples of the more distinctive freeliving larvae to appeal to the more casual observer. Meanwhile, the present authors should be congratulated on completion of this mammoth task.