Through a retinue of professionals in Brussels, farming unions have shaped agricultural policy in Britain. The focus on their members’ interests has given them a guiding star when confronted with the inordinate complexities of the subject. Thus, baffled civil servants and politicians have readily taken their advice. That could change with the repatriation of policy to the UK.

As Malcolm Smith writes in his introduction, there seemed no likelihood of Britain leaving the EU when he embarked on this enterprising volume. What started out as an explanation of the impact of intensive agriculture on wildlife and the benefits of wildlife-friendly farming has been overtaken by events. Brexit has added a policy purpose to Smith’s ambition. He has responded with ten proposed policy changes, which he titles ‘new furrows’ in the final chapter. Whatever their merits, they are unlikely to have much traction now. Is it likely that in future all farmers in receipt of public money will be required to trot off to attend college-based courses to be educated in such matters as farm wildlife-habitat management? With the Agriculture Bill ploughing on through a sea of uncertainty, such exhortations may have missed the boat.

View this book on the NHBS website

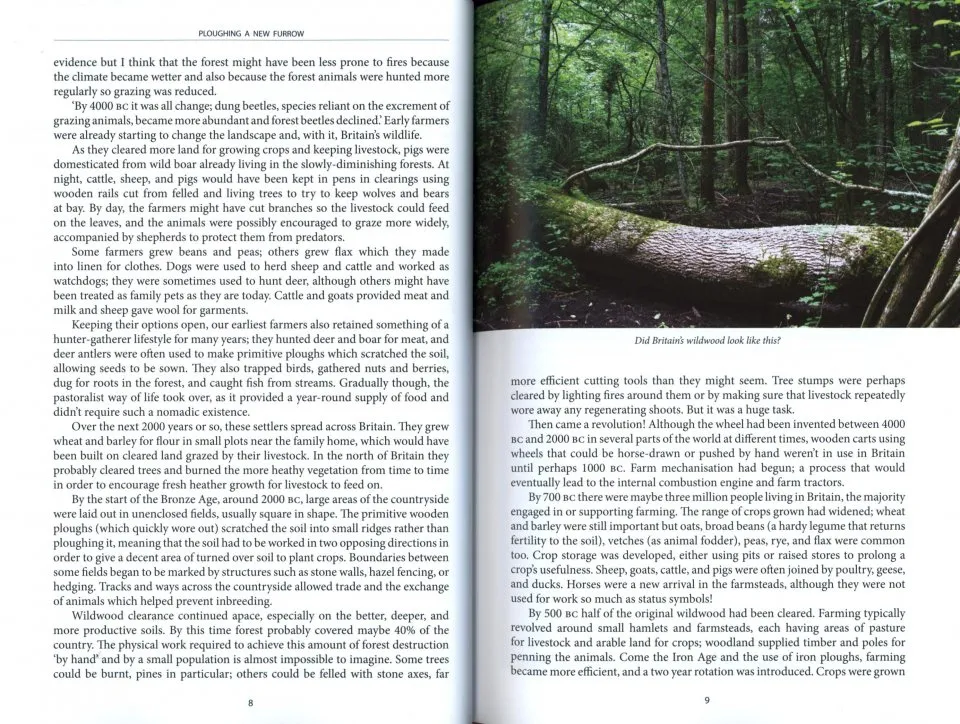

To tell the story of farming the author starts with the blank, tundra-covered sheet of what became Britain, which then acquired a clothing of ‘wildwood’. ‘Sometime before 6000 BC’, he writes, ‘the first farmers ever to arrive on our shores trudged across the flat, marshy land that then linked the east coast of Britain to the European continent.’ The account which follows is inevitably brief – we travel from axes to pesticides in one chapter. British Wildlife readers may consider the early chapters prone to speculation presented as fact, and may find that some of its sweeping statements jar. That may be because they are not the target audience: the constant use of the exclamation mark, signposting those nuggets which the reader should remark on, suggests that this is the case. Text in boxes with such headings as ‘What did the Romans do for farming?’ and ‘Cometh the hour, cometh the man’ (about Jethro Tull and Turnip Townsend) give a similar impression.

Smith sets out the toll on wildlife, a familiar litany driven largely by publicly funded agricultural policy. There is no doubt that he cares about these losses, and from my perspective he is on the side of the angels. I wish that he had looked for more personal ways of lifting the text, as, for example, Mark Cocker has done in his splendid account of what has happened to nature in Britain, Our Place – Can We Save Britain’s Wildlife Before It Is Too Late? Tackling the ins and outs of the Common Agricultural Policy and the economics of farming in a way which excites the reader is no easy task, and my sympathies are with the author in this attempt. Smith deploys a great many facts and figures, necessary but hard going, and he has found a good way to illustrate the benefits of wildlife-friendly farming. He has visited a succession of farms, describes what the farmers have done for wildlife, and quotes liberally from them – glimpses of sun cross an overcast text.

A great deal of information has been marshalled in this volume. Will it find an audience, and make a difference? I hope so. Yet the rapidly shifting ground of farm policy will not make this easy. The author is an accomplished environmental journalist. The downside of that genre is its limited shelf life. Fortune has not smiled when it comes to the timing of this worthy championing of nature-friendly farming.